Using Melatonin? Here’s How It Can Impair Your Blood Sugar Levels: Melatonin and blood Sugar

Melatonin is best known for sleep.

Some may also know it from longevity research, where it’s studied for its cellular protective effects.

But what many might not realize is that melatonin is a hormone.

And hormones, by definition, exert regulatory effects on multiple target tissues throughout the body.

In melatonin’s case, it exerts these effects through MT1 & MT2 receptors in multiple organs: in the pancreas, in blood vessels, in adipose tissue, within the reproductive axis, among others.

In this article, we’ll focus on one of those sites: the pancreas.

Because when melatonin binds to receptors in pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin, it can alter blood sugar control—an effect few expect from a supplement they’ve taken for sleep.

If you’re using melatonin—or considering it—this article unpacks what you need to know so you can enjoy the sleep benefits of melatonin without the unexpected/unintended effects on blood sugar.

Here’s what you’ll find in this article:

- What human studies show about melatonin impairing blood sugar control

- How supplement timing and your genetics affect melatonin’s effects on your blood sugar regulation

- What this evidence means for your melatonin use

- A quick check tool to see whether your melatonin use is supportive both sleep and metabolic health

Let’s get started.

Section 2: Human Studies Show Melatonin Can Impair Blood Sugar Control – how melatonin affects blood sugar

Human trials show that melatonin supplementation can impair blood sugar control—even in otherwise healthy adults.

In a placebo-controlled study, 21 healthy women completed glucose tolerance tests after taking 5 mg of melatonin in the morning on one day and in the evening on another day.

Both scenarios impaired glucose handling, but through different pathways:

- Morning melatonin suppressed insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells

- Evening melatonin reduced insulin sensitivity in muscle and other tissues

Although the mechanisms differed—reduced insulin secretion in the morning versus reduced tissue sensitivity in the evening—the result was the same: less effective blood sugar regulation.

In another study, a 3-month trial in men with type 2 diabetes found similar results.

Those given 10 mg melatonin nightly showed a 12% reduction in insulin sensitivity compared to placebo—even though their diet and exercise stayed the same.

The men also had lower insulin secretion, indicating disruption at both the level of insulin production and its action in tissues.

You can read more about the details of these two studies in my article, The 2 Metabolic Systems Melatonin Disrupts—Even in Healthy Adults.

Together, these studies show melatonin can impair blood sugar control across the metabolic spectrum—from healthy adults to those already managing diabetes.

But here’s where the story gets more nuanced:

- Some studies find people with naturally low nighttime melatonin levels have higher diabetes risk.

- Animal studies often show melatonin improves insulin sensitivity.

- A few human trials actually report modest benefits in blood pressure or waist size alongside melatonin supplementation.

So how can melatonin both protect and impair blood sugar regulation?

Section 3: Why Studies on Melatonin & Blood Sugar Show Conflicting Results

The role of melatonin in metabolism and insulin release has been “controversial”… both improved and impaired glucose tolerance has been reported after melatonin therapy. — Tuomi et al.

The contradictory results don’t reflect real disagreement—they reflect unaddressed factors.

Specifically: the timing of melatonin relative to meals and individual genetic sensitivity to melatonin’s effects.

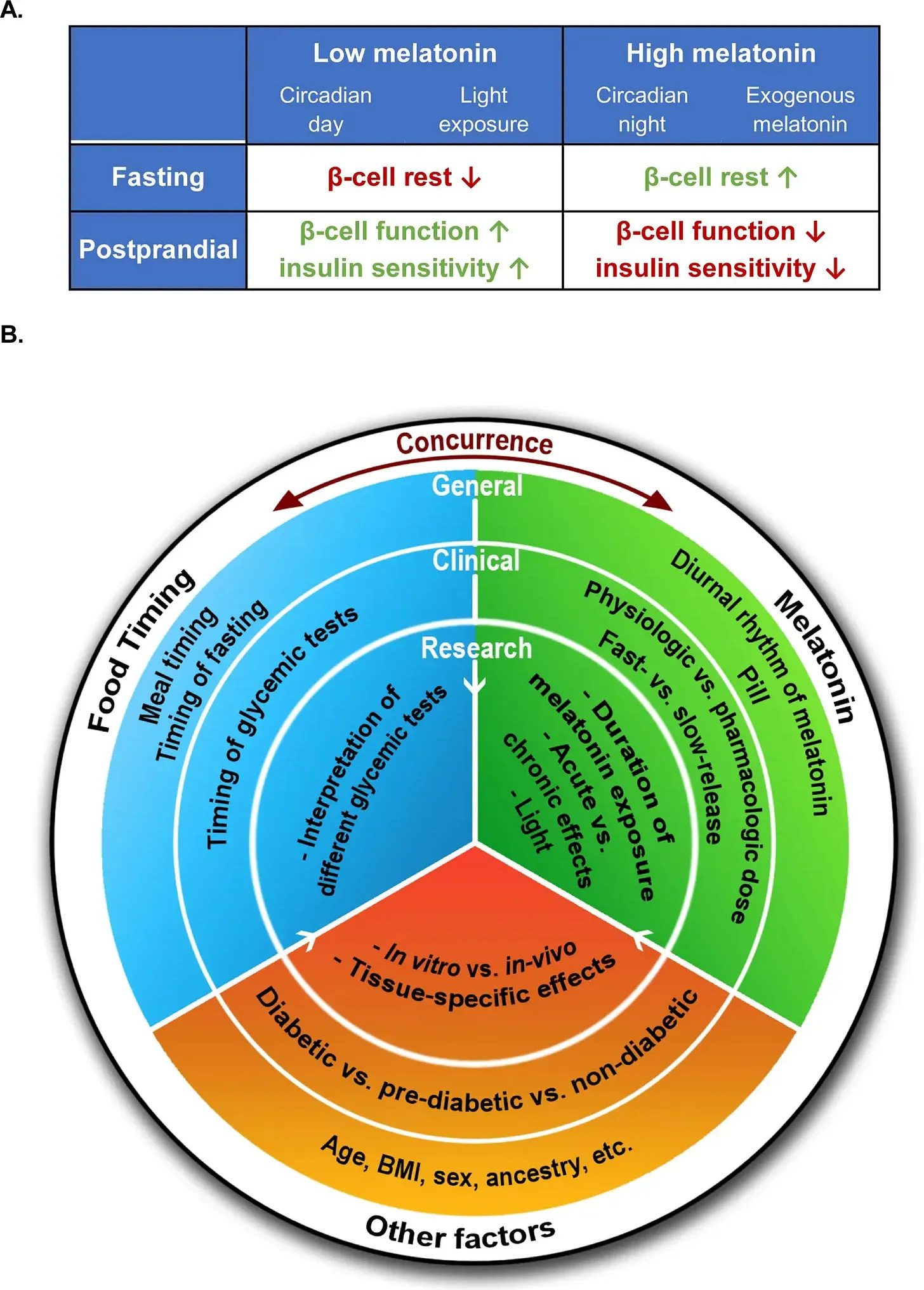

Factor 1: Timing—When Melatonin Is Elevated In Relation To Meals Affects Melatonin’s Impact

Melatonin has a natural role in metabolism: suppressing insulin release during overnight fasting.

When you stop eating at night, rising melatonin helps prevent unnecessary insulin secretion. This prevents low blood sugar during sleep while allowing insulin-producing cells to recover for the next day.

This system works well—until melatonin and food processing overlap.

As Garaulet and colleagues explained: “The concurrence of elevated melatonin concentrations and food intake adversely influences glucose metabolism in humans.”

This overlap can happen in two common scenarios:

- Eating late at night when natural melatonin is already rising

- Taking melatonin supplements within hours of dinner

When elevated melatonin coincides with food intake, it creates a metabolic conflict. Your body receives a “fasting” signal (from melatonin) while simultaneously processing a “fed” state (from food).

The result is reduced insulin release, impaired glucose uptake, and higher blood sugar.

This timing effect explains why studies with different meal–supplement intervals report opposite outcomes:

- During true overnight fasting: Melatonin supports metabolic balance and helps insulin-producing cells recover

- While food is being processed: Melatonin impairs insulin release and glucose tolerance

But timing alone doesn’t account for all the variability.

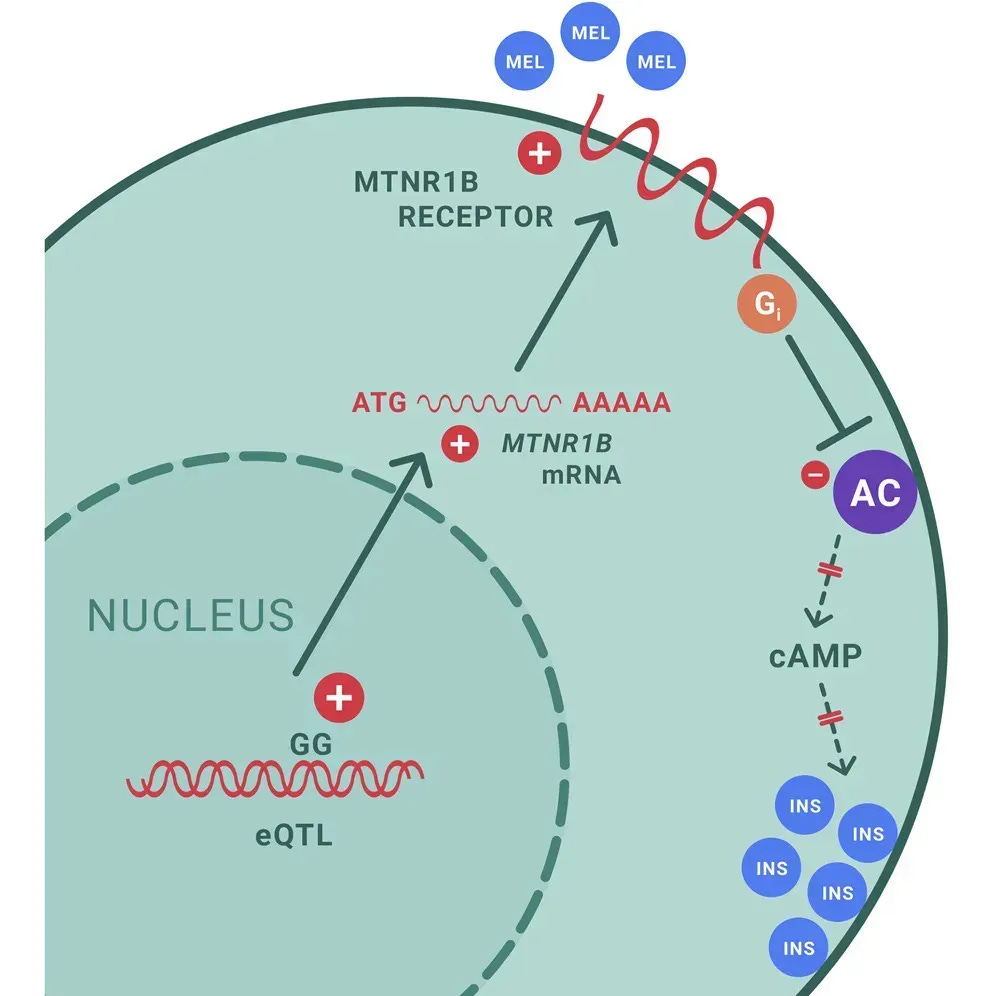

Factor 2: The Genetic Component—Individual Variation in Blood Sugar Response to Melatonin

Melatonin’s effects on blood sugar control vary from person to person.

About 30% of people carry a genetic variant that makes them more susceptible to melatonin’s insulin-suppressing effects.

The variant—called rs10830963—affects the MTNR1B gene, which codes for melatonin receptors in pancreatic cells that produce insulin.

Individuals who carry this variant have increased melatonin receptor expression in their insulin-producing cells. This means their pancreas responds more strongly to melatonin’s “stop making insulin” signal.

To test this, researchers first identified people’s genetic variants, then invited them back to see how each group responded to melatonin supplementation.

When melatonin was given to individuals with different genetic backgrounds, insulin secretion dropped in everyone—regardless of genetics.

However, the effect varied widely:

- Individuals with the genetic variant showed much stronger insulin suppression

- They also showed lower insulin-to-glucagon ratios, favoring higher blood sugar

- The effect was strongest in people with two copies of the variant

Melatonin treatment reduced insulin secretion and raised glucose levels more extensively in risk G-allele carriers. — Tuomi et al.

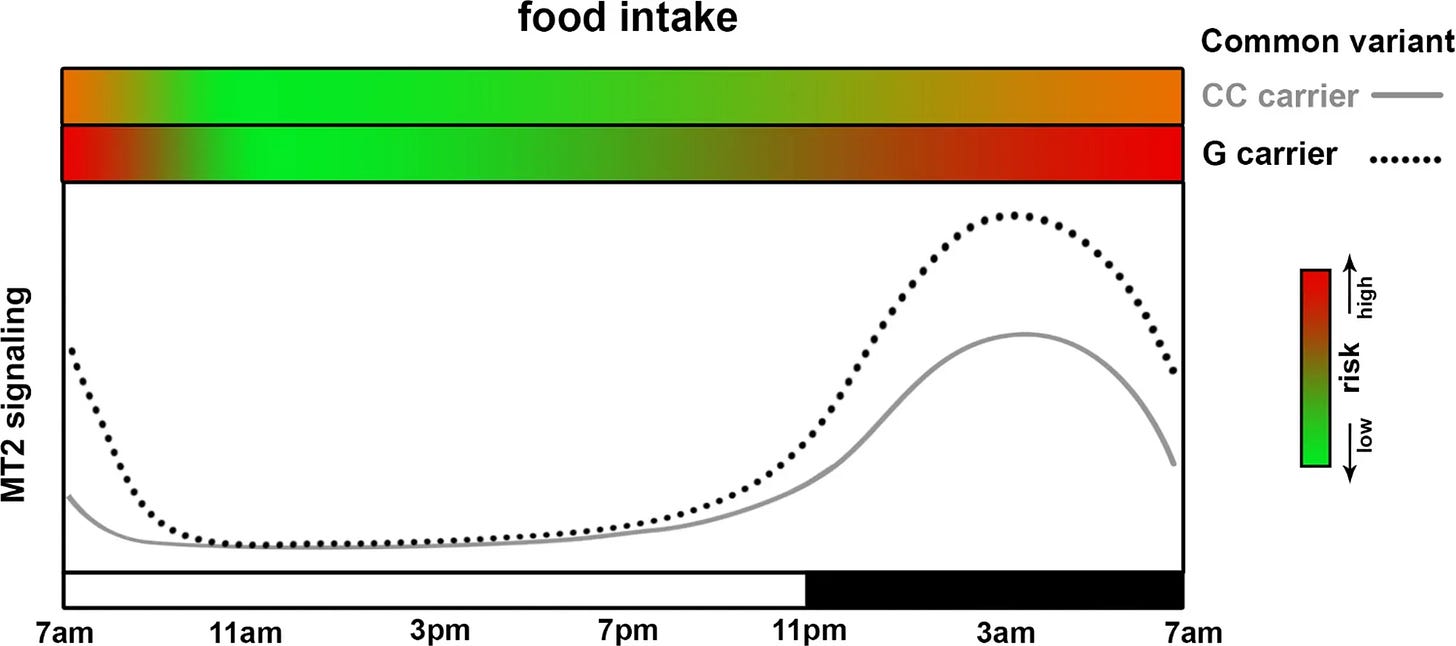

In practical terms, a melatonin dose and timing that looks “tolerable” in one person can lead to blood sugar elevation in another—because of genetic background.

This makes the question less about whether melatonin is helpful or harmful—and more about how it’s used in your specific context.

Section 4: What This Means for Your Current Melatonin Use (Or If You Are Considering Melatonin)

With these considerations in mind, melatonin can be used in ways that support sleep while minimizing its potential to disrupt blood sugar:

- Meal timing explains when melatonin becomes problematic: when it overlaps with food processing

- Genetics explains who experiences the strongest effects: the 30% carrying variants that amplify melatonin’s insulin-suppressing signal

Here are some example scenarios where melatonin use may contribute to metabolic concerns, and scenarios where it more closely fits melatonin’s natural role in the body:

Higher-risk scenarios:

- Taking melatonin within hours of eating — raises blood sugar while food is still being processed (especially for genetic variant carriers)

- Late evening meals combined with bedtime melatonin — compounds both timing issues and extends the overlap period

- Standard over-the-counter or even higher doses — keep melatonin elevated longer, creating stronger and more persistent glucose disruption (especially for genetic variant carriers)

Lower-risk scenarios:

- Melatonin during true overnight fasting periods — aligns with melatonin’s natural metabolic role of supporting the fasted state

- Properly timed supplementation in people with typical receptor sensitivity — accounts for individual circadian patterns and genetic background

- Physiological doses (0.1-0.3mg) rather than typical over-the-counter doses doses — more closely mimics natural levels without creating excessive exposure or lingering into the morning

- Effect of melatonin timing on glucose metabolism; interaction with common genetic variant in MTNR1B. The two green-red gradient bars on the top of the panel indicate the risk of glucose intolerance (red as high, green as low) when food intake happens at the given MT2 signaling level (dependent both on genotype and circadian phase)

As Garaulet noted: “The relative timing between elevated melatonin concentrations and glycemic challenge should be considered to better understand the mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities of melatonin signaling.”

These contrasts highlight some of the melatonin use scenarios that separate higher- from lower-risk use.

Now, the practical question becomes: where does your own use fall?

That’s what the next section will help you check.

Section 5: A Quick Check for Your Melatonin Use—Is It Supporting Your Sleep & Metabolic Health?

If you use melatonin, this quick check can help you see whether your current melatonin use fits patterns that tend to support sleep and stable blood sugar—or drifts toward a potentially metabolically disruptive profile:

Check if any of these apply to your current melatonin use:

☐ You take melatonin within 3-4 hours of your last meal

☐ You’re using 5mg or higher doses without knowing if you actually need supplementation

☐ You take melatonin right at bedtime rather than earlier in the evening

☐ You eat dinner after 7 PM and take melatonin before bed

☐ You experience stronger-than-expected effects from standard doses

☐ You notice blood sugar changes, morning grogginess, or energy crashes with melatonin use

☐ You’re over 60 and using the same dose recommendations as younger adults

☐ Sleep quality hasn’t noticeably improved, even with regular melatonin use

☐ You’ve never tested whether you actually have low melatonin production

☐ Afternoon fatigue or blood sugar swings are more noticeable on days you supplement with melatonin

How to read this check:

If several of these boxes apply, your current approach might be working against stable blood sugar.

That doesn’t necessarily mean melatonin is wrong for you—it means the way it’s used probably benefits from closer attention.

The key insight: melatonin isn’t universally helpful or harmful—its effects depend on your genetics, when you take it relative to meals and your individual circadian timing.

If you’d like to go deeper, my 21-day melatonin sleep recovery blueprint

If you are already using melatonin but still getting unpredictable results—some nights it helps, others it does not—it is easy to end up increasing the dose, switching brands, and spending more without a better outcome. Over time, that pattern delivers the worst combination: inconsistent sleep, ongoing expense, and higher risk of morning grogginess and impaired glucose handling.

The 21-Day Melatonin Sleep Recovery Blueprint + Decision Matrix is designed to end that uncertainty—without requiring lab testing. In 21 days, you follow a structured sequence to:

- determine whether melatonin is actually relevant to your sleep pattern or was never the right lever in the first place

- adjust timing and dose in a physiologically aligned way, so you are not relying on guesswork or chronic high doses

At the end of the 21 days, the 21-Day Melatonin Sleep Recovery Blueprint + Decision Matrix, gives you enough data to make a clear decision: continue with an optimized melatonin plan, or stop investing in a supplement that is not meaningfully improving your sleep.

You can get it here:

Section 6: Moving Beyond Simple Supplement Protocols For Sleep Recovery

A note before we close: I’ve never taken melatonin myself.

I’ve learned that individual inputs—whether supplements or other approaches—that appear straightforward often have multiple, sometimes conflicting effects in practice.

For me, that lesson came with ashwagandha.

I had assumed it was a reliable stress support.

Yet after months of use, my experience was uneven. Some days it eased recovery and sleep. Other days, it seemed to do nothing—or even made me feel more awake at night.

When I began reviewing the literature, the mechanisms were not definitive.

Some studies suggest possible modulation of GABA signaling, others point to cortisol dampening effects, but neither provided a clear explanation for the variability I noticed. The most reasonable interpretation I came to is that ashwagandha was acting through several pathways at once, with outcomes that were not always aligned.

That experience taught me a principle I carry into everything, whether it’s melatonin, magnesium, or any other input: nothing is truly straightforward once you account for the layered complexity of individual biology.

Because, no input acts in isolation.

Most engage multiple systems—neurotransmitters, hormones, metabolic regulators—many of which we still don’t fully understand.

One effect might support your goal while another works against it.

This is why meaningful health improvements—whether sleep, energy, or cognitive resilience—rarely come from universal approaches. Instead, they come from understanding how they interact within your specific biology & adjusting with a structured, personalized methodology.

So, just because I’ve personally never taken melatonin (& probably won’t in the near future), doesn’t mean that you as the reader couldn’t have a genuine need for it and can benefit from intentional use—it all comes down to personalization.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

References

- Basini, G., & Grasselli, F. (2024). Role of melatonin in ovarian function. Animals (Basel), 14(4), 644.

- Baskett, J. J., Broad, J. B., Wood, P. C., Duncan, J. R., Pledger, M. J., English, J., & Arendt, J. (2003). Does melatonin improve sleep in older people? A randomised crossover trial. Age and Ageing, 32(2), 164–170.

- Brydon, L., Petit, L., Delagrange, P., Strosberg, A. D., & Jockers, R. (2001). Functional expression of MT2 (Mel1b) melatonin receptors in human PAZ6 adipocytes. Endocrinology, 142(10), 4264–4271.

- Buscemi, N., et al, (2004). Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 108). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Cajochen, C., Münch, M., Knoblauch, V., Blatter, K., & Wirz-Justice, A. (2006). Age-related changes in the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep. Chronobiology International, 23(1–2), 461–474.

- Candyce Hamel, & Horton, J. (2022). Melatonin for the treatment of insomnia: A 2022 update. CADTH Health Technology Review.

- Comai, S., & Gobbi, G. (2024). Melatonin, melatonin receptors and sleep: Moving beyond traditional views. Journal of Pineal Research, 76(7), e13011.

- Cook, J. S., Sauder, C. L., & Ray, C. A. (2011). Melatonin differentially affects vascular blood flow in humans. American Journal of Physiology–Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 300(2), H670–H674.

- Duffy, J. F., Wang, W., Ronda, J. M., & Czeisler, C. A. (2022). High dose melatonin increases sleep duration during nighttime and daytime sleep episodes in older adults. Journal of Pineal Research, 73(1), e12801.

- Ferracioli-Oda, E., Qawasmi, A., & Bloch, M. H. (2013). Meta-analysis: Melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e63773.

- Ferlazzo, N., Andolina, G., Cannata, A., et al. (2020). Is melatonin the cornucopia of the 21st century? Antioxidants (Basel), 9(11), 1088.

- Fu, K. (2025, June 6). The 3 forms of sleep disruption that shrink your brain—and how to tell if your sleep is actually protecting you from cortical atrophy, brain shrinkage and neurodegeneration. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/brain-shrinkage-sleep/

- Fu, K. (2025, June 12). Melatonin for sleep: Why it often fails—and what to do instead to stay asleep to prevent brain aging, cognitive decline, and toxin buildup at night. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-for-sleep/

- Fu, K. (2025, July 29). The 2 metabolic systems melatonin disrupts—even in healthy adults. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.substack.com/p/melatonin-metabolic-effects

- Fu, K. (2025, September 10). Melatonin as a longevity molecule? Safety data, metabolic risks, and antioxidant promise. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-as-a-longevity-molecule

- Fu, K. (2025, September 16). Melatonin can impair blood sugar regulation (& what this means for your melatonin use). The Longevity Vault. https://open.substack.com/pub/thelongevityvault/p/melatonin-blood-sugar

- Garaulet, M., et al, (2015). Common type 2 diabetes risk variant in MTNR1B worsens the deleterious effect of melatonin on glucose tolerance in humans. Metabolism, 64(12), 1650–1657.

- Garaulet, M., et al, (2020). Melatonin effects on glucose metabolism: Time to unlock the controversy. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 31(3), 192–204.

- Givler, D., et al,(2023). Chronic administration of melatonin: Physiological and clinical considerations. Neurology International, 15(1), 518–533.

- Gobbi, G., & Comai, S. (2019). Differential function of melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors in REM and NREM sleep. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 87.

- Guan, Q., Wang, Z., Cao, J., Dong, Y., & Chen, Y. (2022). Mechanisms of melatonin in obesity: A review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(1), 218.

- Hardeland, R. (2018). Melatonin and inflammation—Story of a double-edged blade. Journal of Pineal Research, 65(4), e12525

- José Cipolla-Neto, & Gaspar do Amaral, F. (2018). Melatonin as a hormone: New physiological and clinical insights. Endocrine Reviews, 39(6), 990–1028.

- Lauritzen, E. S., et al,. (2022). Three months of melatonin treatment reduces insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. Journal of Pineal Research, 73(1), e12809.

- Lelak, K., Vohra, V., Neuman, M. I., Toce, M. S., & Sethuraman, U. (2022). Pediatric melatonin ingestions—United States, 2012–2021. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(22), 725–729.

- Luboshitzky, R., Shen-Orr, Z., Nave, R., Lavi, S., & Lavie, P. (2002). Melatonin administration alters semen quality in healthy men. Journal of Andrology, 23(4), 572–578.

- Martín Giménez, et al., (2022). Melatonin as an anti-aging therapy for age-related cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, 888292.

- Marupuru, S., et al., (2022). Use of melatonin and/or ramelteon for the treatment of insomnia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(17), 5138.

- Menczel Schrire, Z., et al, (2022). Safety of higher doses of melatonin in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pineal Research, 72(2), e12782.

- Morris, C. J., et al., (2015). Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(17), E2225–E2234.

- Peneva, V. M., Terzieva, D. D., & Mitkov, M. D. (2023). Role of melatonin in the onset of metabolic syndrome in women. Biomedicines, 11(6), 1580.

- Reiter, R. J., et al., (2016). Melatonin as an antioxidant: Under promises but over delivers. Journal of Pineal Research, 61(3), 253–278.

- Reiter, R. J., et al., (2024). Mitochondrial melatonin: Beneficial effects in protecting against heart failure. Life, 14(1), 88.

- Rubio-Sastre, P., Scheer, F. A., Gómez-Abellán, P., Madrid, J. A., & Garaulet, M. (2014). Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening. Sleep, 37(10), 1715–1719.

- Savage, R. A., Zafar, N., Yohannan, S., et al. (2025). Melatonin. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534823/

- Skene, D. J., & Swaab, D. F. (2003). Melatonin rhythmicity: Effect of age and Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental Gerontology, 38(1–2), 199–206.

- Smythe, G., & Lazarus, L. (1973). Growth hormone regulation by melatonin and serotonin. Nature, 244, 230–231.

- Sletten, T. L., et al., (2010). Timing of sleep and its relationship with the endogenous melatonin rhythm. Frontiers in Neurology, 1, 137.

- Tuft, C., Matar, E., Menczel Schrire, Z., Grunstein, R. R., Yee, B. J., & Hoyos, C. M. (2023). Current insights into the risks of using melatonin as a treatment for sleep disorders in older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 18, 49–59.

- Tuomi, T., et al.,. (2016). Increased melatonin signaling is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Cell Metabolism, 23(6), 1067–1077.

- Valcavi, R., Zini, M., Maestroni, G. J., Conti, A., & Portioli, I. (1993). Melatonin stimulates growth hormone secretion through pathways other than the growth hormone-releasing hormone. Clinical Endocrinology, 39(2), 193–199.

- Wang, L. M., Suthana, N. A., Chaudhury, D., Weaver, D. R., & Colwell, C. S. (2005). Melatonin inhibits hippocampal long-term potentiation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 22(9), 2231–2237.

- Wyatt, J. K., et al.,(2006). Sleep-facilitating effect of exogenous melatonin in healthy young men and women is circadian-phase dependent. Sleep, 29(5), 609–618.

- Zhang, H. M., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Melatonin: A well-documented antioxidant with conditional pro-oxidant actions. Journal of Pineal Research, 57(2), 131–146.

- Zhong, J., et al.,(2025). Melatonin biosynthesis and regulation in reproduction. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 16, 1630164.

- Zibolka, J., et al., (2018). Distribution and density of melatonin receptors in human main pancreatic islet cell types. Journal of Pineal Research, 65(1), e12480.