Melatonin for Older Adults: Timing, Dose, and Sleep Quality — “I Take 5mg of Melatonin — Why Do I Still Wake Up at 3 AM?”

➤ My friend’s dad recently asked me this question, and it perfectly captures what so many of you have shared with me about melatonin but haven’t been able to solve:

“I started taking melatonin after years of struggling to stay asleep through the night. The melatonin definitely helps me fall asleep faster, but I still wake up around 3-4am and can’t fall back asleep. I’m in bed by 10pm, take my 5mg melatonin around 9:30pm, but I still wake up hours before my alarm. Any advice on how to stay asleep? Should I increase my dose?“

He’d tried everything.

Different brands, formulations, doses.

Taking it earlier at 9:30pm just shifted the wake-up to 3am instead of 4am.

Nothing worked.

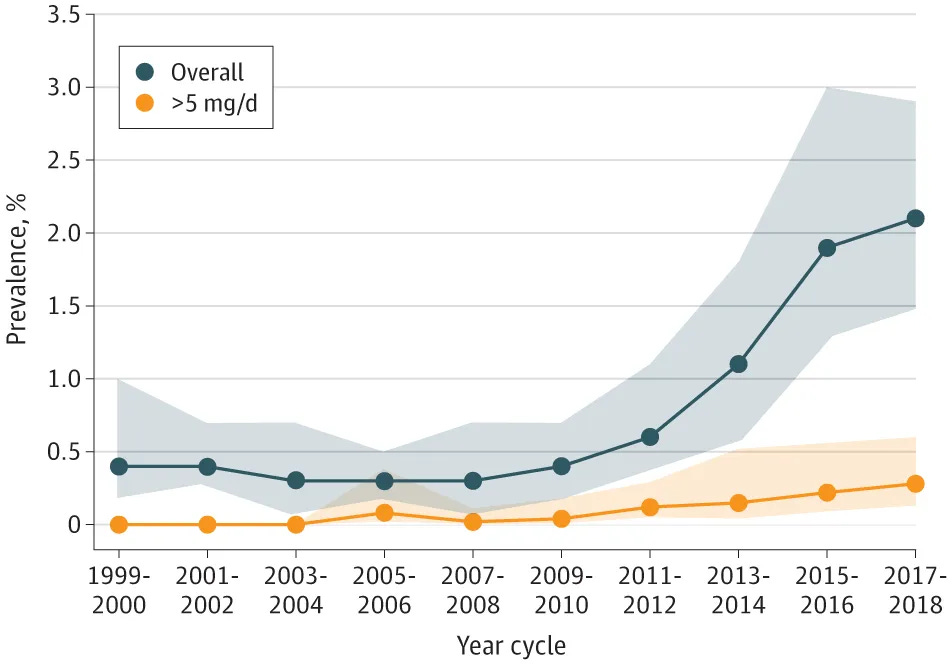

Melatonin use has more than 2x’ed in the last decade, encouraged by over-the-counter access and mainstream promotion.

Yet most of that use happens without guidance.

Beyond its role in sleep, melatonin also acts on several organs, including the pancreas. That means melatonin supplementation can influence how the body manages blood sugar — something I explored in detail in my earlier article on melatonin and glucose.

But this post isn’t a rehash of that discussion.

Instead, we’re stepping back to look at melatonin more broadly — and the use patterns that often cause it to disappoint in real-world use.

If you’re using melatonin — or considering it — this article unpacks the most common pitfalls to avoid.

More importantly, you’ll understand why your current melatonin approach might not be working for you & how I helped one individual improve his early morning awakenings by using melatonin in a different way than conventional advice suggests.

Here’s what we’ll walk through together:

- The 4 common pitfalls in real-world melatonin use — and why they matter for sleep, metabolism, and longevity

- Why age, medications, and eating patterns make melatonin more complex than most people realize

- A step-by-step look at how I helped my friend’s father improve his sleep—from 3:15 a.m. wake-ups to sleeping through his alarm

Let’s get started.

By the way, If you’ve been following my work on hormones and sleep, you’ll know how much depth there is beneath the surface.

If you’re ready to go deeper and take a systems-based approach to improving your sleep, Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

or

4 Common Pitfalls in Melatonin Use—And Why They Matter for Your Sleep (& Longevity)

Pitfall 1. Poor Melatonin Timing from Both Circadian & Metabolic Perspectives

The most common approach involves taking melatonin 5-30 minutes before.

This creates 2 problems.

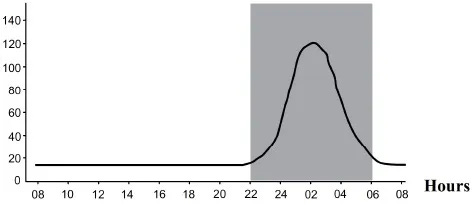

- Circadian mismatch: bedtime dosing rarely aligns with your circadian biology. Melatonin works most effectively when taken earlier in relation to your biological night, not at the moment you want to fall asleep

- Metabolic overlap: this timing frequently overlaps with active digestion. Many individuals eat dinner late, then take melatonin within hours of that meal. This overlaps elevated melatonin with active glucose processing—a scenario shown to impair insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance.

What feels like the intuitive choice—taking melatonin at bedtime—doesn’t account for either circadian biology or the metabolic impacts of melatonin–food overlap.

Pitfall 2. Typical Over-the-Counter Melatonin Doses

Physiological nighttime melatonin levels typically require just 0.1–0.3 mg to replicate.

Yet most over-the-counter supplements contain 3–10 mg per dose—marketed as “extra strength” for better sleep. Some publications even advocate for much larger doses for other non-sleep reasons.

However, studies show that a single 5 mg dose of melatonin can keep plasma levels elevated at 10 times above natural peaks, even 6 hours after ingestion—Garaulet, 2020

This means melatonin can remain active into morning hours, when it should naturally be low.

The result can include reduced morning insulin secretion and impaired blood sugar handling during breakfast.

Pitfall 3. Age-Related Susceptibility to High Doses

Advanced age adults are often more sensitive to standard melatonin doses because of age-related changes in drug metabolism and circadian function.

Liver metabolism slows with age—with many studies showing reduced activity of CYP enzymes—and kidney clearance declines as well.

As a result, melatonin exposure can persist longer in some older adults.

Additionally, as we age, our melatonin rhythms tend to show lower amplitude and more variability.

This suggests that older adults may respond differently to supplemental melatonin—possibly experiencing longer residual effects or greater sensitivity to standard supplement doses and timing mismatches.

In practice, the same dose that clears quickly in a 35-year-old can still be present at meaningful levels when a 65-year-old is waking and preparing to process breakfast. The outcome may include morning grogginess, reduced insulin sensitivity, and higher glucose levels.

Yet standard dosing recommendations rarely account for these age-related changes, treating a 35-year-old and 65-year-old as if their physiology responds identically to the same hormone dose.

If you’d like to go deeper, my 21-day melatonin sleep recovery blueprint

—built around the 5 personalized adjustments I used to help my friend’s dad with his sleep—is available. If you’d like t

o access the 21-Day Melatonin Sleep Recovery Blueprint + Decision Matrix , you can do so here:

Pitfall 4. Night Eaters & Melatonin Supplementation

Night eating—consuming the bulk of calories in the evening—creates unfavorable interactions with melatonin use.

Taking melatonin before bed in this context produces overlap between elevated hormone levels and ongoing blood sugar processing. Studies show this overlap can impair insulin function, especially in individuals with MTNR1B variants, where the glucose rise is more pronounced.

Night eating is common among adults dealing with stress, irregular schedules, or social patterns that push dinner later.

Yet guidance on melatonin rarely accounts for these feeding habits.

Intake of an usual dose (i.e., 1 to 5 mg), generates “within the hour after ingestion, melatonin concentrations 10-100 times higher than the physiological nocturnal peak, ” “with a return to basal concentrations in 4 to 8 hours” —Tordjman

Shift workers face similar challenges through chronic circadian misalignment. Epidemiological data show that shift work increases type 2 diabetes risk, with rotating night shift nurses showing diabetes risk that correlates with both shift duration and intensity.

Standard melatonin recommendations typically don’t account for these additional circadian challenges or meal-timing overlaps.

These 4 common pitfalls with how individuals use melatonin help explain why supplementation can sometimes worsen rather than improve sleep quality, and why some notice morning grogginess or energy dips that seem unrelated to sleep duration.

But understanding the problems is only helpful if you know how to navigate around them.

So, let me show you how I helped my friend’s father …

How I Helped My Friend’s Father Sleep Until 7AM

When my friend’s father first came to me, he had been taking 5mg of melatonin for ~6 months.

It helped him fall asleep faster—within 20 minutes instead of his usual hour of tossing. But he still woke at 3:15am consistently.

His first question: “Should I increase to 10mg?”

When I suggested we first try reducing his dose instead, he was skeptical. He expected that more melatonin would be the solution, not less.

He also preferred to start without doing a melatonin profile test—which meant we couldn’t map his melatonin levels.

So, instead, I explained what we know from research and melatonin profiles I’ve reviewed: that physiological replacement, if it’s needed at all, typically requires 0.1–0.3mg.

At 5mg, his melatonin levels were already many times higher than natural peaks, potentially creating an unnatural hormonal pattern that disrupted sleep architecture rather than supporting it.

So I guided him through:

1. Lowering the dose in a way that minimize rebound like patterns

Dropping melatonin straight from 5mg to a fraction of a milligram can in some cases trigger restlessness or unsettled sleep as the body adjusts. By reducing the dose in measured steps, we avoided these effects and could more clearly see whether the new level was supporting sleep.

2. Melatonin metabolism

I also explained that older adults can metabolize melatonin more slowly due to age-related changes in liver enzyme activity and clearance. This means standard supplement doses can linger into the morning, when melatonin should naturally be low. In practice, this not only heightens grogginess but can also interfere with glucose handling—making physiologic dosing all the more important.

3. Melatonin timing

The other challenge was finding his optimal timing window.

Individual biological night can vary by up to 4-5 hours between people,

Even so, based both on circadian research and on the melatonin profiles I had seen in individuals I have worked with, taking it either at bedtime or even 1 hour before was still likely not the right time.

We kept the lower dose consistent while exploring different timing patterns based on his natural sleepiness cues and wake patterns.

Here are the sleep improvements he began to notice after we’ve been working together for 10 days:

- Days 5-10: The 3:15am wake-ups shifted to around 5am—still early, but meaningful progress. He noticed less grogginess when he did wake.

- Days 11-20: Reaching 6am. The fragmented final hours of sleep were becoming more consolidated.

- Days 21-30: Sleeping through to his 7am alarm for the first time in years.

Importantly, what transformed wasn’t just sleep duration—his sleep quality seemed to improve.

The racing thoughts at 3am diminished. The morning brain fog lifted. He found himself needing less afternoon caffeine to maintain energy.

Now we’re working on the next phase: gradually reducing the melatonin further to see if he still needs supplementation at all.

His sleep architecture appears to have stabilized enough that he may be able to maintain good sleep without it—his body perhaps just needed time to reset after months of higher doses.

The Broader Takeaway: The “How” of Health Strategies & the Timeline of Results

This is just one individual’s experience, but it illustrates an important principle:

When a strategy (in this case melatonin) doesn’t seem to be working, the solution is not always to add more.

It’s often worth exploring whether the how of applying a strategy—such as, in the case of melatonin, dose and timing—can be adjusted to work better.

And, in some cases, whether that strategy (in this case, melatonin) is needed at all.

There’s also the matter of timeline.

Sometimes when we make adjustments to established patterns—myself included—we are eager for results within a few days.

However, its useful to remember meaningful health changes & improvements often take weeks if not months. In my friend’s father’s case, he had been taking melatonin for about 6 months, and the rhythm shifts happened gradually—10 days, then 20, then 30.

For individuals making changes to lifestyle patterns that have been in place for years or decades—whether that means long-term use, higher doses, or entrenched habits—the body may need even longer to recalibrate.

Six to seven weeks, sometimes several months, is not unusual.

In other words, the process of health improvement is measured in weeks and months, not days. Keeping this pace in mind makes it easier for us to stay with the process long enough for change to emerge & sustain.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

References

- Deacon S and Arendt J (1995) Melatonin-induced temperature suppression and its acute phase-shifting effects correlate in a dose-dependent manner in humans. Brain Res 688 (1–2), 77–85.

- Tordjman S, Chokron S, Delorme R, Charrier A, Bellissant E, Jaafari N, Fougerou C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017 Apr;15(3):434-443. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666161228122115. PMID: 28503116; PMCID: PMC5405617.

- Kennaway DJ. The dim light melatonin onset across ages, methodologies, and sex and its relationship with morningness/eveningness. Sleep. 2023 May 10;46(5):zsad033. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsad033. PMID: 36799668; PMCID: PMC10171641.

- LeBourgeois MK, Carskadon MA, Akacem LD, Simpkin CT, Wright KP Jr, Achermann P, Jenni OG. Circadian phase and its relationship to nighttime sleep in toddlers. J Biol Rhythms. 2013 Oct;28(5):322-31. doi: 10.1177/0748730413506543. PMID: 24132058; PMCID: PMC3925345.

- Li J, Somers VK, Xu H, Lopez-Jimenez F, Covassin N. Trends in Use of Melatonin Supplements Among US Adults, 1999-2018. JAMA. 2022 Feb 1;327(5):483-485. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23652. PMID: 35103775; PMCID: PMC8808329.

- Burgess HJ, Park M, Wyatt JK, Rizvydeen M, Fogg LF. Sleep and circadian variability in people with delayed sleep-wake phase disorder versus healthy controls. Sleep Med. 2017 Jun;34:33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.019. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28522096; PMCID: PMC5514558.

- Gooneratne NS, Edwards AY, Zhou C, Cuellar N, Grandner MA, Barrett JS. Melatonin pharmacokinetics following two different oral surge-sustained release doses in older adults. J Pineal Res. 2012 May;52(4):437-45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00958.x. Epub 2012 Feb 21. PMID: 22348451; PMCID: PMC3682489.

- Tuft C, Matar E, Menczel Schrire Z, Grunstein RR, Yee BJ, Hoyos CM. Current Insights into the Risks of Using Melatonin as a Treatment for Sleep Disorders in Older Adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2023 Jan 12;18:49-59. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S361519. PMID: 36660543; PMCID: PMC9842516.

- Peneva, V.M.; Terzieva, D.D.; Mitkov, M.D. Role of Melatonin in the Onset of Metabolic Syndrome in Women. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1580. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061580

- Tuomi T, Nagorny CLF, Singh P, Bennet H, Yu Q, Alenkvist I, Isomaa B, Östman B, Söderström J, Pesonen AK, Martikainen S, Räikkönen K, Forsén T, Hakaste L, Almgren P, Storm P, Asplund O, Shcherbina L, Fex M, Fadista J, Tengholm A, Wierup N, Groop L, Mulder H. Increased Melatonin Signaling Is a Risk Factor for Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2016 Jun 14;23(6):1067-1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.009. Epub 2016 May 12. PMID: 27185156.

- Garaulet M, Qian J, Florez JC, Arendt J, Saxena R, Scheer FAJL. Melatonin Effects on Glucose Metabolism: Time To Unlock the Controversy. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Mar;31(3):192-204. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.11.011. Epub 2020 Jan 1. PMID: 31901302; PMCID: PMC7349733.

- Garaulet M, Gómez-Abellán P, Rubio-Sastre P, Madrid JA, Saxena R, Scheer FA. Common type 2 diabetes risk variant in MTNR1B worsens the deleterious effect of melatonin on glucose tolerance in humans. Metabolism. 2015 Dec;64(12):1650-7. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.003. Epub 2015 Aug 14. PMID: 26440713; PMCID: PMC4856010.

- Garaulet M, Qian J, Florez JC, Arendt J, Saxena R, Scheer FAJL. Melatonin Effects on Glucose Metabolism: Time To Unlock the Controversy. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Mar;31(3):192-204. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.11.011. Epub 2020 Jan 1. PMID: 31901302; PMCID: PMC7349733.

- José Cipolla-Neto, Fernanda Gaspar do Amaral, Melatonin as a Hormone: New Physiological and Clinical Insights, Endocrine Reviews, Volume 39, Issue 6, December 2018, Pages 990–1028, https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2018-00084

- Savage RA, Zafar N, Yohannan S, et al. Melatonin. [Updated 2024 Feb 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534823/

- Rubio-Sastre P, Scheer FA, Gómez-Abellán P, Madrid JA, Garaulet M. Acute melatonin administration in humans impairs glucose tolerance in both the morning and evening. Sleep. 2014 Oct 1;37(10):1715-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4088. PMID: 25197811; PMCID: PMC4173928.

- Lauritzen ES, Kampmann U, Pedersen MGB, Christensen LL, Jessen N, Møller N, Støy J. Three months of melatonin treatment reduces insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes-A randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Pineal Res. 2022 Aug;73(1):e12809. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12809. Epub 2022 Jun 9. PMID: 35619221; PMCID: PMC9540532.

- C.J. Morris, J.N. Yang, J.I. Garcia, S. Myers, I. Bozzi, W. Wang, O.M. Buxton, S.A. Shea, & F.A.J.L. Scheer, Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (17) E2225-E2234, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418955112 (2015).

- Cajochen C, Münch M, Knoblauch V, Blatter K, Wirz-Justice A. Age-related changes in the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1-2):461-74. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545813. PMID: 16687319.

- Skene DJ, Swaab DF. Melatonin rhythmicity: effect of age and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Gerontol. 2003 Jan-Feb;38(1-2):199-206. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00198-5. PMID: 12543278.

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.; Chuffa, L.G.d.A.; Simko, F.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A. Mitochondrial Melatonin: Beneficial Effects in Protecting against Heart Failure. Life 2024, 14, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14010088

- Sletten TL, Vincenzi S, Redman JR, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SM. Timing of sleep and its relationship with the endogenous melatonin rhythm. Front Neurol. 2010 Nov 1;1:137. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2010.00137. PMID: 21188265; PMCID: PMC3008942.

- Baskett JJ, Broad JB, Wood PC, Duncan JR, Pledger MJ, English J, Arendt J. Does melatonin improve sleep in older people? A randomised crossover trial. Age Ageing. 2003 Mar;32(2):164-70. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.164. PMID: 12615559.

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Pandya R, Hooton N, Tjosvold L, Hartling L, Baker G, Vohra S, Klassen T. Melatonin for Treatment of Sleep Disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 108. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publication No. 05-E002-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2004.

- Marupuru S, Arku D, Campbell AM, Slack MK, Lee JK. Use of Melatonin and/on Ramelteon for the Treatment of Insomnia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 31;11(17):5138. doi: 10.3390/jcm11175138. PMID: 36079069; PMCID: PMC9456584.

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One. 2013 May 17;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773. PMID: 23691095; PMCID: PMC3656905.

- Fu, K. (2025, June 6). The 3 forms of sleep disruption that shrink your brain—and how to tell if your sleep is actually protecting you from cortical atrophy, brain shrinkage and neurodegeneration. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/brain-shrinkage-sleep/

- Fu, K. (2025, June 12). Melatonin for sleep: Why it often fails—and what to do instead to stay asleep to prevent brain aging, cognitive decline, and toxin buildup at night. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-for-sleep/

- Fu, K. (2025, July 29). The 2 metabolic systems melatonin disrupts—even in healthy adults. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-metabolic-systems

- Fu, K. (2025, September 10). Melatonin as a longevity molecule? Safety data, metabolic risks, and antioxidant promise. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-as-a-longevity-molecule

- Fu, K. (2025, September 16). Melatonin can impair blood sugar regulation (& what this means for your melatonin use). The Longevity Vault. https://open.substack.com/pub/thelongevityvault/p/melatonin-blood-sugar

- Benloucif S, Burgess HJ, Klerman EB, Lewy AJ, Middleton B, Murphy PJ, Parry BL, Revell VL. Measuring melatonin in humans. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Feb 15;4(1):66-9. PMID: 18350967; PMCID: PMC2276833.

- Arendt J, Aulinas A. Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin. [Updated 2022 Oct 30]. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK550972/

- Nogueira LM, Sampson JN, Chu LW, Yu K, Andriole G, Church T, Stanczyk FZ, Koshiol J, Hsing AW. Individual variations in serum melatonin levels through time: implications for epidemiologic studies. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 23;8(12):e83208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083208. PMID: 24376664; PMCID: PMC3871612.