Are My Hormones Affecting My Sleep? An Overlooked Reason Hormone Therapy Falls Short

Many individuals with low hormones—whether from aging or another medical reason—try supplemental testosterone, estrogen, or progesterone.

The hope is that more hormone should restore sleep, energy, and mood.

But results are often mixed. Some notice improvement; others see little change, or even new sleep difficulties.

Part of the reason is that all 3 hormones affect sleep, and affect sleep in different ways:

- Testosterone can support deep sleep under physiologic replacement, while supraphysiologic dosing can disrupt sleep architecture.

- Estrogen modulates circadian timing, body temperature regulation, and elements of REM sleep patterns.

- Progesterone enhances calming brain activity through its metabolite’s interactions with GABA receptors, helping reduce wake after sleep onset.

One of the core pieces often overlooked is that hormones don’t act directly—they must first be received and processed by the body’s tissues.

When it comes to sleep, this binding and signaling take place in brain regions such as the hypothalamus, basal forebrain, and brainstem nuclei—areas that regulate circadian timing, arousal, and the depth of sleep.

By the way, If you’ve been following my work on hormones and sleep, you’ll know how much depth there is beneath the surface.

If you’re ready to go deeper and take a systems-based approach to improving your sleep, Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

or

Section 2: Hormone Function Relies on Utilization, Not Just Levels or Production

You may recall, I’ve mentioned in a preview article that hormone function is not determined by hormone levels or hormone production alone.

Once a hormone is made by the body, it still has to move through several stages—being carried through the body, converted into usable forms, delivered to tissues, used by the tissues, and eventually removed from the body.

All of these steps matter, but here we’ll focus on receptor sensitivity & utilization— the ability of target tissues to recognize and respond to the hormone once it arrives

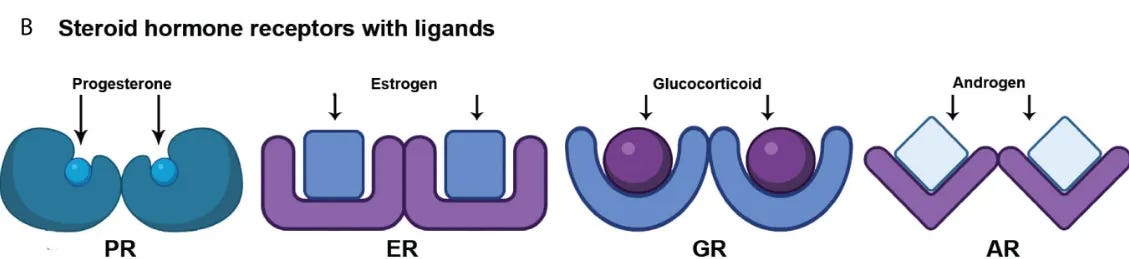

In simplified terms, receptors are the entry point for hormones to act on a cell.

In more specific terms: a receptor is a protein on or inside a cell that recognizes a hormone molecule and enables the hormonal signal to be transmitted.

There are 3 features of hormone receptors that affect how effectively a hormone signal is transmitted once the hormone reaches a cell:

- Receptor number (expression): how many receptors are present in a tissue such as the hypothalamus or hippocampus. Fewer receptors mean less capacity for hormone action, regardless of circulating levels.

- Binding affinity and activation efficiency: how strongly the hormone attaches, and whether the receptor activates properly once bound. Aging and oxidative stress can alter expression and impair signaling efficiency.

- Downstream signaling capacity: the ability of the receptor–hormone complex to turn on genes, produce proteins, and adjust neural or metabolic functions. If this cascade is weak, the hormone’s impact remains limited.

This is why hormone supplementation, whether testosterone, estrogen, or progesterone, often produces variable results.

Supplementation changes circulating levels but does not address receptor sensitivity.

If receptors are sparse, unresponsive, or poorly coupled to downstream signaling, additional hormone may not improve sleep (or other changes) in the way one expects.

…and that leads us to the question of what shapes receptor sensitivity over a lifetime.

Section 3: So, What Affects Hormone Receptor Sensitivity?

Several factors affect how responsive hormone receptors are, and why two individuals with similar hormone levels can potentially have different sleep outcomes:

- Genetics set the baseline. Variants in receptor genes shape sensitivity from birth. For example, the androgen receptor gene has regions called CAG repeats. A shorter repeat length generally produces more responsive receptors, while longer repeats reduce sensitivity. Genetic variation in estrogen and progesterone receptors also influences signaling, though patterns differ from androgen receptors. This creates individual differences in how responsive someone is to a given hormone’s effects (on sleep or otherwise).

- Aging reduces receptor sensitivity. With advancing age, receptor expression in brain tissue declines. This means there are fewer receptors available for hormones to bind. Human basal forebrain studies show nuclear androgen receptor staining declines with age. Estrogen and progesterone receptor expression also change with age, accompanied by alterations in binding efficiency and downstream signaling.

- Why this matters for sleep. The receptors for testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone are located in brain regions that impact circadian timing, stress recovery, and sleep depth—especially the hypothalamus and hippocampus. As receptor number and sensitivity decline, the same circulating hormone level produces a weaker biological effect.

Declining receptor sensitivity may be one (of many) contributing factors to why sleep becomes lighter and more fragmented with age, especially when hormone levels are normal.

So, is there anything we can do to maintain hormone responsiveness?

Section 4: The Good News: Hormone Receptor Sensitivity Can Change — What Research Shows

The encouraging news is that receptor sensitivity is not entirely fixed.

While genetics set the baseline and aging reduces expression, there is some evidence that activity and environment can shape how responsive receptors remain.

- Animal studies: In rodents, estrogens promote synapse and spine formation in the hippocampus, and enriched environments and neural stimulation can modulate the magnitude of these estrogen-linked plasticity effects. Androgens acting through their receptors also support hippocampal structure and plasticity, such as maintaining dendritic spines, and studies show that mild exercise elevates local dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and requires AR activity for exercise-induced neurogenesis. These models illustrate that receptor responsiveness is not static: even in aging tissue, environmental inputs can enhance or preserve receptor-driven plasticity.

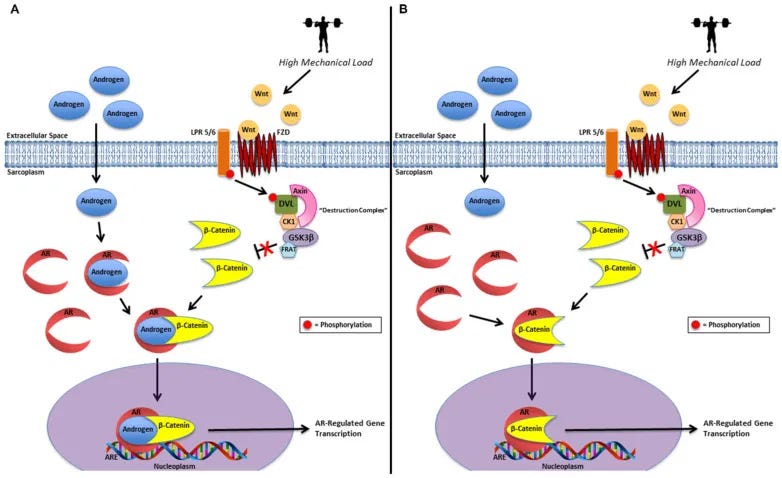

- Human studies: In muscle, resistance training often increases AR activity and in several studies increases AR content. Individuals with higher receptor expression in muscle show greater gains from training, demonstrating that receptors can be upregulated and functionally amplified in peripheral tissues.

- The caveat: Direct human evidence for increasing receptor number or sensitivity in the brain is limited. Most data come from animal studies or from peripheral tissues such as muscle. Still, taken together, these findings suggest that receptors are dynamic. While the evidence for brain receptor plasticity in humans remains indirect, lifestyle factors that influence receptor function in muscle and in animal brain models make it biologically plausible that similar mechanisms could support human brain signaling.

In short: receptors decline with age, but they are not beyond influence.

What we do daily can either diminish their responsiveness more quickly or help preserve and even support their function over time.

Section 5: Actionable Steps for Supporting Hormone Receptor Sensitivity

If receptor sensitivity influences how well hormones shape sleep, the next question is: what can be done?

While direct human evidence on modulating receptor function in the brain is limited, several systemic levers have support:

- Resistance trainingIn human muscle, resistance training increases androgen receptor expression and strengthens signaling efficiency. Regular, progressive sessions that challenge large muscle groups are associated with favorable receptor adaptations in muscle.

- Reduce oxidative stressHigh oxidative stress can disrupt receptor expression and signaling by damaging proteins and impairing co-activators. Approaches that lower oxidative load—such as aerobic conditioning and limiting excess alcohol—create a more supportive environment for receptor function.

- Support synaptic plasticityHormone receptors operate within synapses, where they interact with neurotransmitter systems to shape circadian rhythm and sleep depth. Animal studies show that both estrogen and androgens influence synapse formation in hippocampus, and that physical or cognitive activity helps maintain synaptic plasticity. While human brain data are sparse, it is plausible that preserving synaptic health indirectly supports receptor sensitivity in sleep-related circuits.

These strategies may not change receptor expression in the brain overnight, but they influence the broader conditions that affect how effectively hormones can act.

Hormone Receptors Are the Gatekeepers of Hormone Effects (on Sleep & Beyond)

Hormone production — and the circulating levels it creates — is necessary for optimal hormone function, but it is only the starting point.

Whether testosterone or estrogen improve sleep depends on receptor sensitivity—the number of receptors available, how efficiently they bind, and how well the downstream signal is carried forward.

Direct human data on changing receptor sensitivity in the brain are still limited.

Yet the broader picture is clear: lifestyle choices such as resistance training, reducing oxidative stress, and maintaining synaptic plasticity shape the environment in which receptors operate.

In this way, you can improve how effectively your existing hormones influence sleep without needing higher doses.

Bottom line: production sets the supply; sensitivity determines the impact.

By supporting receptor function, you improve overall hormone function.

That means the hormones you already have—or those you supplement—can more effectively support sleep, energy, overall vitality, so you feel your best for decades to come.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

References

- Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012 Nov;67(11):1140-52.

- Lee J, Kim HJ. Normal Aging Induces Changes in the Brain and Neurodegeneration Progress: Review of the Structural, Biochemical, Metabolic, Cellular, and Molecular Changes. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022 Jun 30;14:931536. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.931536. PMID: 35847660; PMCID: PMC9281621.

- Shi L, Ko S, Kim S, Echchgadda I, Oh TS, Song CS, Chatterjee B. Loss of androgen receptor in aging and oxidative stress through Myb protooncoprotein-regulated reciprocal chromatin dynamics of p53 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase PARP-1. J Biol Chem. 2008 Dec 26;283(52):36474-85.

- Nerattini, M., Berti, V., Matthews, D.C. et al. Quantitative and simplified [18F] fluoroestradiol positron emission tomography (PET) measures of brain estrogen receptor expression. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2025).

- Liu PY, Reddy RT. Sleep, testosterone and cortisol balance, and ageing men. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022 Dec;23(6):1323-1339. doi: 10.1007/s11154-022-09755-4. Epub 2022 Sep 24. PMID: 36152143; PMCID: PMC9510302.

- Roth GS, Hess GD. Changes in the mechanisms of hormone and neurotransmitter action during aging: current status of the role of receptor and post-receptor alterations. A review. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982 Nov;20(3):175-94.

- Low KL, Tomm RJ, Ma C, Tobiansky DJ, Floresco SB, Soma KK. Effects of aging on testosterone and androgen receptors in the mesocorticolimbic system of male rats. Horm Behav. 2020 Apr;120:104689.

- Maki, Pauline M. PhD1; Panay, Nick BSc, FRCOG2; Simon, James A. MD, MSCP3. Sleep disturbance associated with the menopause. Menopause 31(8):p 724-733, August 2024. | DOI: 10.1097/GME.0000000000002386

- Davey RA, Grossmann M. Androgen Receptor Structure, Function and Biology: From Bench to Bedside. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016 Feb;37(1):3-15.

- Low KL, Tomm RJ, Ma C, Tobiansky DJ, Floresco SB, Soma KK. Effects of aging on testosterone and androgen receptors in the mesocorticolimbic system of male rats. Horm Behav. 2020 Apr;120:104689.

- Foster TC. Role of estrogen receptor alpha and beta expression and signaling on cognitive function during aging. Hippocampus. 2012 Apr;22(4):656-69. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20935.

- Dart, D.A., Bevan, C.L., Uysal-Onganer, P. et al. Analysis of androgen receptor expression and activity in the mouse brain. Sci Rep 14, 11115 (2024).

- Maioli S, Leander K, Nilsson P, Nalvarte I. Estrogen receptors and the aging brain. Essays Biochem. 2021 Dec 17;65(6):913-925. doi: 10.1042/EBC20200162.

- Vaudry H, Ubuka T, Soma KK, Tsutsui K. Editorial: Recent Progress and Perspectives in Neurosteroid Research. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 27;13:951990. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.951990.

- Hirtz R, Libuda L, Hinney A, Föcker M, Bühlmeier J, Holterhus PM, Kulle A, Kiewert C, Hebebrand J, Grasemann C. Size Matters: The CAG Repeat Length of the Androgen Receptor Gene, Testosterone, and Male Adolescent Depression Severity. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Oct 20;12:732759.

- Morton RW, Sato K, Gallaugher MPB, Oikawa SY, McNicholas PD, Fujita S, Phillips SM. Muscle Androgen Receptor Content but Not Systemic Hormones Is Associated With Resistance Training-Induced Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy in Healthy, Young Men. Front Physiol. 2018 Oct 9;9:1373. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01373. PMID: 30356739; PMCID: PMC6189473.

- Cardaci TD, Machek SB, Wilburn DT, Heileson JL, Willoughby DS. High-Load Resistance Exercise Augments Androgen Receptor-DNA Binding and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling without Increases in Serum/Muscle Androgens or Androgen Receptor Content. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 15;12(12):3829. doi: 10.3390/nu12123829. PMID: 33333818; PMCID: PMC7765240.

- Ahtiainen JP, Hulmi JJ, Kraemer WJ, Lehti M, Nyman K, Selänne H, Alen M, Pakarinen A, Komulainen J, Kovanen V, Mero AA, Häkkinen K. Heavy resistance exercise training and skeletal muscle androgen receptor expression in younger and older men. Steroids. 2011 Jan;76(1-2):183-92. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.10.012. Epub 2010 Nov 9. PMID: 21070797.

- Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse. Physiol Rev. 2015 Jul;95(3):785-807. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2014. PMID: 26109339; PMCID: PMC4491541.

- Nokia MS, Lensu S, Ahtiainen JP, Johansson PP, Koch LG, Britton SL, Kainulainen H. Physical exercise increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis in male rats provided it is aerobic and sustained. J Physiol. 2016 Apr 1;594(7):1855-73. doi: 10.1113/JP271552.

- Ishunina TA, Fisser B, Swaab DF. Sex differences in androgen receptor immunoreactivity in basal forebrain nuclei of elderly and Alzheimer patients. Exp Neurol. 2002 Jul;176(1):122-32. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7907. PMID: 12093089.

- Saha S, Dey S, Nath S. Steroid Hormone Receptors: Links With Cell Cycle Machinery and Breast Cancer Progression. Front Oncol. 2021 Mar 12;11:620214. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.620214. PMID: 33777765; PMCID: PMC7994514.

- Kumar R, Litwack G. Structural and functional relationships of the steroid hormone receptors’ N-terminal transactivation domain. Steroids. 2009 Nov;74(12):877-83. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.07.012. Epub 2009 Aug 8. PMID: 19666041; PMCID: PMC3074935.

- Di Donato, M., Moretti, A., Sorrentino, C. et al. Filamin A cooperates with the androgen receptor in preventing skeletal muscle senescence. Cell Death Discov. 9, 437 (2023).

- Gentile, G., De Stefano, F., Sorrentino, C. et al. Androgens as the “old age stick” in skeletal muscle. Cell Commun Signal 23, 167 (2025).

- Sheppard PAS, Choleris E, Galea LAM. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus in response to estrogens in female rodents. Mol Brain. 2019 Mar 18;12(1):22.

- Okamoto M, Hojo Y, Inoue K, Matsui T, Kawato S, McEwen BS, Soya H. Mild exercise increases dihydrotestosterone in hippocampus providing evidence for androgenic mediation of neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Aug 7;109(32):13100-5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210023109.

- Cardaci TD, Machek SB, Wilburn DT, Heileson JL, Willoughby DS. High-Load Resistance Exercise Augments Androgen Receptor-DNA Binding and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling without Increases in Serum/Muscle Androgens or Androgen Receptor Content. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 15;12(12):3829.

- Barsky, S.T., Monks, D.A. The role of androgens and global and tissue-specific androgen receptor expression on body composition, exercise adaptation, and performance. Biol Sex Differ 16, 28 (2025).

- Ciarloni, A.; delli Muti, N.; Ambo, N.; Perrone, M.; Rossi, S.; Sacco, S.; Salvio, G.; Balercia, G. Contribution of Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Polymorphism to Human Reproduction. DNA 2025, 5, 9.

- Roth GS, Hess GD. Changes in the mechanisms of hormone and neurotransmitter action during aging: current status of the role of receptor and post-receptor alterations. A review. Mech Ageing Dev. 1982 Nov;20(3):175-94.