“Why can’t I stay Asleep Longer Than 5-6 Hours?”

➤ Someone recently asked me this question, and it perfectly captures what so many people experience but can’t explain:

“I’ve had this issue for a very long time now where I wake up too early and then drift in and out of restless sleep for the last 1-2 hours of sleep and none of the standard sleep habit tricks help. I will go to bed at around 22:00 and consistently wake up around 3 am, falling in and out of sleep 3-4 times until 5 am with a lot of movement in my sleep causing achiness as well.”

They’d tried everything.

Going to bed earlier just shifted the wake-up to 2am instead of 3am. They’d planned entire days around sleep—timing exercise, sunlight, meals, winding down hours before bed with no screens. Complete caffeine detox. Melatonin. Even prescription sleep aids.

Nothing worked.

By the way, If you’ve been following my work on hormones and sleep, you’ll know how much depth there is beneath the surface.

If you’re ready to go deeper and take a systems-based approach to improving your sleep, Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

or

Why Standard Sleep Advice Misses the Real Problem

When you’ve optimized everything about sleep onset but still can’t stay asleep past 5-6 hours, you’re dealing with something deeper than sleep hygiene. The issue isn’t getting to sleep—it’s what happens to your sleep architecture in that second half of the night.

Waking up after 5-6 hours and drifting in and out isn’t just “light sleep.”

It’s often a mismatch between your sleep systems and the signals that should sustain deeper stages. After sleep onset, your body’s ability to maintain continuous rest depends less on external cues and more on how internal recovery systems behave during those later hours.

For someone focused on longevity, this matters beyond just feeling tired.

Fragmented sleep in the second half of the night disrupts the deeper stages where your brain clears metabolic waste, consolidates memory, and maintains cognitive resilience—the very processes that protect against cognitive decline and preserve mental sharpness as you age.

My Approach: Three Sleep Architecture Disruptions

I used to struggle with this exact pattern.

Sometimes it was falling asleep, other times it was waking up at 2 or 3am and not being able to get back to deep rest. I tried all the standard approaches for years without consistent results.

What finally helped wasn’t another sleep hygiene tip.

It came from understanding the underlying mechanisms that govern sleep continuity—specifically what disrupts the transition between sleep stages after that first window.

Here are the three factors I’ve found most often drive this pattern:

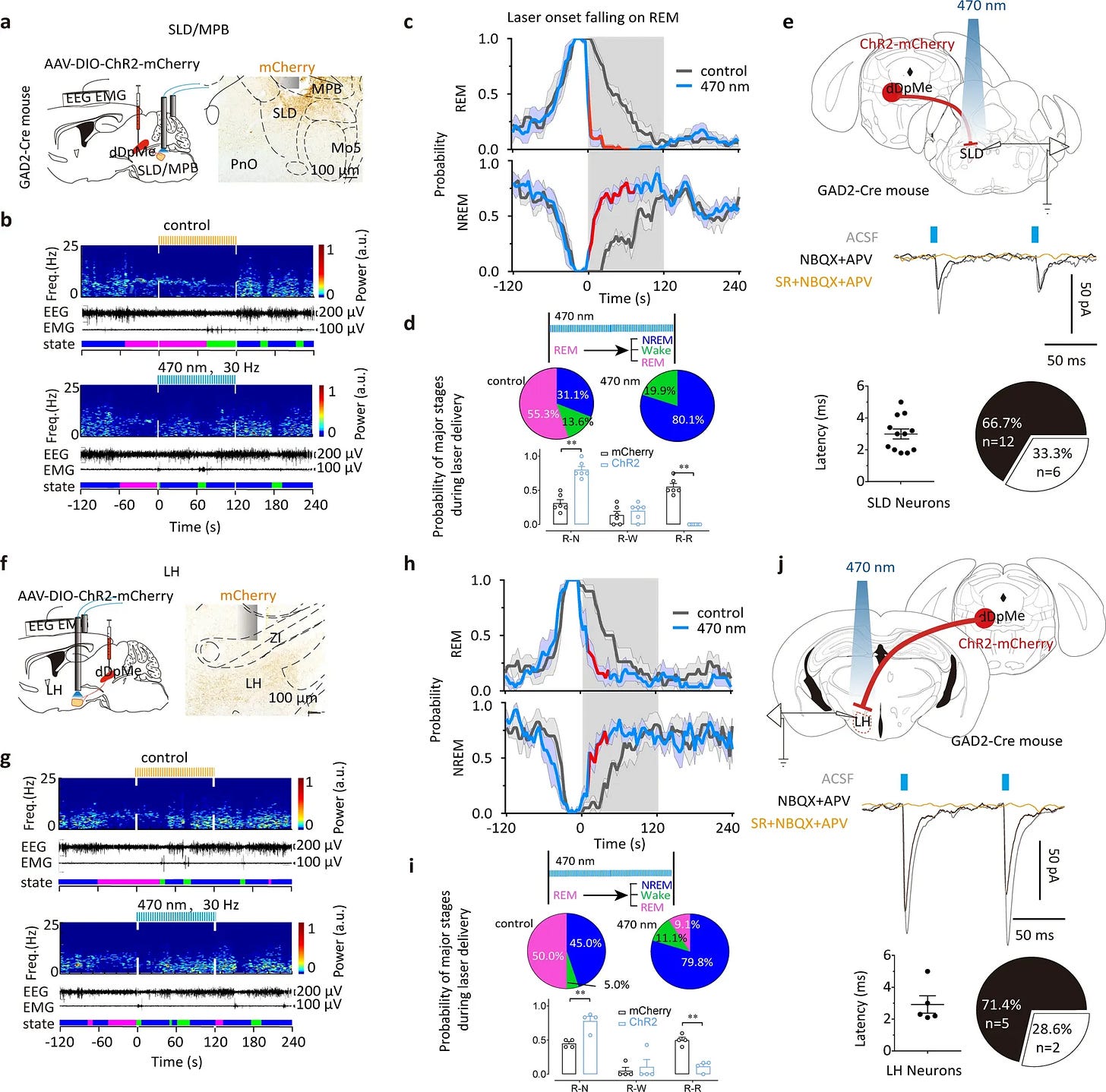

1. Cholinergic–GABAergic Imbalance in REM Initiation

The switch between REM and non-REM sleep is governed by a delicate balance between cholinergic activity (which promotes REM) and GABAergic activity (which promotes deep sleep).

When GABA tone is insufficient—or acetylcholine spikes too early—you may enter REM too soon and too frequently, disrupting the normal sequencing of restorative stages.

This creates a cycle where you get some sleep, but not the sustained deep phases needed for true recovery.

2. Inadequate Daytime Sleep Pressure

Sleep pressure builds through adenosine accumulation during wakefulness, especially with physical exertion and cognitive effort.

If daytime activity is too sedentary or mistimed—such as intense workouts too late in the day—the first half of the night may be deeper, but not long enough to sustain full rest.

Therefore, the issue isn’t just what you do before bed, but how you build sleep drive throughout the entire day.

3. Melatonin Offset Timing

Melatonin supplementation likely isn’t helping here because it’s designed to initiate sleep, not maintain it.

Natural melatonin rises a couple of hours before bedtime, peaks around 2–4 a.m., and stays elevated for most of the night before tapering toward dawn. When evening light delays this curve, melatonin may no longer align with the chosen sleep window — creating instability or awakenings in the early morning hours.

Taking melatonin right at bedtime doesn’t fix this misalignment. Supplemental melatonin creates a short spike that fades within a few hours, often exaggerating the contrast between the first and second half of the night. Instead of supporting sleep continuity, it can reinforce the early-morning drop-off and disrupt transition into subsequent stages.

The Science Behind Sleep Architecture Breakdown

What most people don’t realize is that sleep isn’t just one continuous state.

Your brain cycles through distinct stages approximately every 90 minutes, with the proportion of deep sleep versus REM changing throughout the night.

In the first half of the night, you get most of your deep sleep—the stage that handles physical recovery and memory consolidation. The second half is when REM sleep becomes more prominent, supporting emotional processing and cognitive function.

When sleep architecture is disrupted, this natural progression breaks down.

Instead of smooth transitions between stages, you get fragmented periods where your brain can’t fully commit to either deep sleep or REM, leaving you in that frustrating in-between state of drifting consciousness.

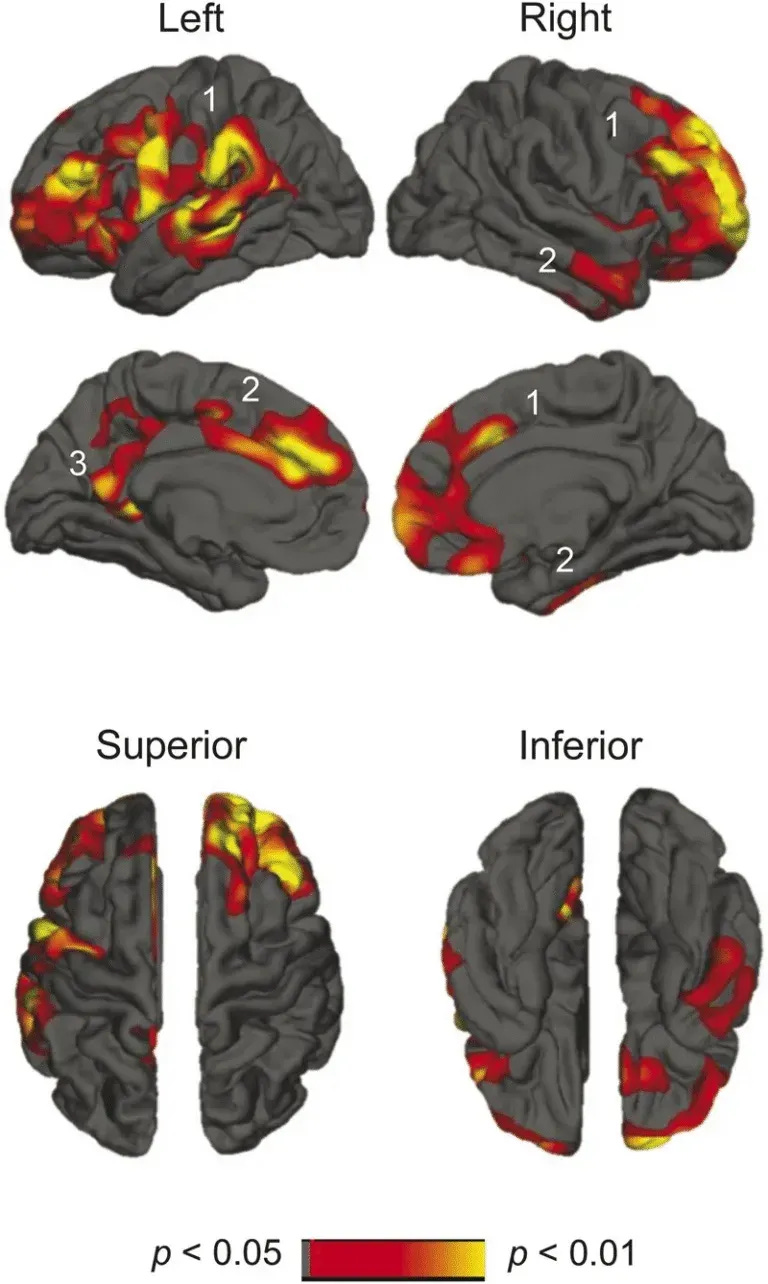

This fragmentation doesn’t just affect how rested you feel—it specifically impairs the brain’s ability to clear metabolic waste through the glymphatic system, which primarily operates during deeper sleep stages.

For longevity-focused individuals, this represents a critical pathway for maintaining cognitive health over decades.

Moving Beyond Sleep Hygiene

Once I stopped focusing only on sleep onset and started looking at what was disrupting continuity, my sleep became much more stable. The breakthrough came from shifting perspective entirely—instead of asking “How do I fall asleep better?” I started asking “What’s preventing my brain from staying in restorative stages?”

The solution wasn’t another bedtime routine—it was understanding how sleep pressure, neurotransmitter balance, and circadian timing interact during those critical hours after 3am. This meant tracking not just when I went to bed, but how different daytime activities affected my adenosine buildup. It meant testing whether late afternoon light exposure was shifting my melatonin curve. It meant recognizing that my 6pm workout might be creating the wrong kind of arousal signal at the wrong time.

Most importantly, it meant treating sleep as a biological system with measurable inputs and outputs, rather than something I could willpower my way through.

When I started testing variables systematically—adjusting one factor at a time and measuring sleep continuity rather than just duration—the 3am wake-ups finally started to resolve.

This is the kind of structured, mechanism-based approach I’m building into The Vault SLEEP OS.

It includes an 8-part recovery framework for people who struggle 1-3 nights a week, and a 9-part intervention for chronic poor sleep patterns, even if you have already fixed light, caffeine, cold room, hygiene.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

References

- Chen, ZK., Dong, H., Liu, CW. et al. A cluster of mesopontine GABAergic neurons suppresses REM sleep and curbs cataplexy. Cell Discov 8, 115 (2022).

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.; Chuffa, L.G.d.A.; Simko, F.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A. Mitochondrial Melatonin: Beneficial Effects in Protecting against Heart Failure. Life 2024, 14, 88.

- Sletten TL, Vincenzi S, Redman JR, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SM. Timing of sleep and its relationship with the endogenous melatonin rhythm. Front Neurol. 2010 Nov 1;1:137.

- Baskett JJ, Broad JB, Wood PC, Duncan JR, Pledger MJ, English J, Arendt J. Does melatonin improve sleep in older people? A randomised crossover trial. Age Ageing. 2003 Mar;32(2):164-70.

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Pandya R, Hooton N, Tjosvold L, Hartling L, Baker G, Vohra S, Klassen T. Melatonin for Treatment of Sleep Disorders. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 108. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publication No. 05-E002-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2004.

- Marupuru S, Arku D, Campbell AM, Slack MK, Lee JK. Use of Melatonin and/on Ramelteon for the Treatment of Insomnia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 31;11(17):5138.

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One. 2013 May 17;8(5):e63773.

- Fu, K. (2025, June 6). The 3 forms of sleep disruption that shrink your brain—and how to tell if your sleep is actually protecting you from cortical atrophy, brain shrinkage and neurodegeneration. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/brain-shrinkage-sleep/

- Fu, K. (2025, June 12). Melatonin for sleep: Why it often fails—and what to do instead to stay asleep to prevent brain aging, cognitive decline, and toxin buildup at night. The Longevity Vault. https://thelongevityvault.com/performance-longevity/melatonin-for-sleep/

- Lee T, Cho Y, Cha KS, Jung J, Cho J, Kim H, Kim D, Hong J, Lee D, Keum M, Kushida CA, Yoon IY, Kim JW. Accuracy of 11 Wearable, Nearable, and Airable Consumer Sleep Trackers: Prospective Multicenter Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2023 Nov 2;11:e50983.

- Robbins, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Sullivan, J.P.; Quan, S.F.; Gilmore, K.; Shaw, S.; Benz, A.; Qadri, S.; Barger, L.K.; Czeisler, C.A.; et al. Accuracy of Three Commercial Wearable Devices for Sleep Tracking in Healthy Adults. Sensors 2024, 24, 6532.

- Cavaillès C, Dintica C, Habes M, Leng Y, Carnethon MR, Yaffe K. Association of Self-Reported Sleep Characteristics With Neuroimaging Markers of Brain Aging Years Later in Middle-Aged Adults. Neurology. 2024 Nov 26;103(10):e209988.

- Kokošová V, Filip P, Kec D, Baláž M. Bidirectional Association Between Sleep and Brain Atrophy in Aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Dec 8;13:726662.

- Vidal-Pineiro, D., Parker, N., Shin, J. et al. Cellular correlates of cortical thinning throughout the lifespan. Sci Rep 10, 21803 (2020).

- Deantoni, M., Reyt, M., Dourte, M. et al. Circadian rapid eye movement sleep expression is associated with brain microstructural integrity in older adults. Commun Biol 7, 758 (2024).

- Cho G, Mecca AP, Buxton OM, Liu X, Miner B. Lower slow wave sleep and rapid eye-movement sleep are associated with brain atrophy of AD-vulnerable regions. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 Jan 14:2025.01.12.632386.

- Sexton CE, Storsve AB, Walhovd KB, Johansen-Berg H, Fjell AM. Poor sleep quality is associated with increased cortical atrophy in community-dwelling adults. Neurology. 2014 Sep 9;83(11):967-73.

- Lim AS, Fleischman DA, Dawe RJ, Yu L, Arfanakis K, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Regional Neocortical Gray Matter Structure and Sleep Fragmentation in Older Adults. Sleep. 2016 Jan 1;39(1):227-35.

- A. Shahid et al. (eds.), STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales