A guide for midlife adults who don’t fit the “classic” apnea mold.

A collaboration between Chris Gouveia, MD (SleepDocs) and Kat Fu, M.S., M.S. (The Longevity Vault).

Chris Gouveia, MD is a board-certified ENT surgeon and sleep apnea specialist practicing in the Bay Area of California. He completed his medical training at UCSF and his sleep fellowship at Stanford University, where co-author Kat Fu (The Longevity Vault) also completed her second masters degree. Dr. Gouveia treats a wide spectrum of OSA and sleep-disordered breathing, with a focus on personalized care. He shares clinical insights and evidence-based analysis on the business, tech, and finance of sleep health through his newsletter at Sleepdocs.

If you picture someone with obstructive sleep apnea, the stereotype is familiar: a heavier middle-aged man, snoring loudly and nodding off at stoplights.

That patient exists.

But in clinic, that’s increasingly not the person I see.

Instead, I see the 52-year-old marathoner who wakes up feeling like he has a hangover without drinking, the 61-year-old executive whose bloodwork looks great but who lives with constant brain fog, and the 58-year-old teacher who eats well, walks every day, does everything right—and still feels like sleep never truly restores her.

They often say some version of:

“My study was ‘normal,’ but something is still wrong with my sleep.”

“My AHI is only 4, so they told me I don’t have sleep apnea.”

“I don’t even snore that much.”

Yet when you look carefully at their sleep and breathing, many of these people still have clinically important sleep-disordered breathing. It just isn’t the cartoon version most of us were taught to recognize.

Before we go further, one key term.

The apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) is the number of times per hour of sleep that breathing stops completely (apnea) or partially collapses (hypopnea) for at least 10 seconds, usually with some drop in oxygen. In adults, an AHI under 5 events per hour is considered normal. AHI between 5 and 15 is labelled mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), 15–30 is moderate, and 30 or more is severe (Harvard Sleep Medicine).

AHI is useful, but it is not the whole story—especially for non-obese, midlife adults. This article walks through:

- how sleep-disordered breathing can show up in people who are not overweight

- how OSA shifts with age and stops looking “classic”

- why a “normal” or “borderline” AHI doesn’t always match how you feel

- how I think about treatment options once we stop treating you as just a number

When apnea doesn’t look dramatic

In leaner or older adults, sleep-disordered breathing often doesn’t present as dramatic gasping or irresistible daytime sleepiness.

More often, what I hear is a long story about waking unrefreshed despite spending seven or eight hours in bed, or about a mental “battery” that drains too fast during the day. People describe slow thinking, word-finding problems, and a creeping loss of confidence in their memory. Mood shifts are common: more irritability, more anxiety, a sense of being “on edge” without a clear trigger.

Night-time often feels light and fragmented. You may wake many times without knowing why, or feel as if you never get into deep sleep even though your watch insists you’ve been in bed long enough. Daytime fatigue is real, but it’s less “falling asleep at red lights” and more “everything takes more effort than it should”.

All of this overlaps with other midlife themes—stress, perimenopause and menopause, caregiving load, work burnout—so it is easy to wave away. From the outside, these patients do not look like the textbook picture of sleep apnea. Many have a body mass index (BMI) in the normal or mildly elevated range. Some exercise regularly. Partners may notice occasional snoring or restless sleep, but nothing theatrical.

Under the surface, though, the airway can still be misbehaving dozens of times an hour. The difference is in how it misbehaves.

Non-obese OSA is common, not rare

For a long time, obesity was taught as the core risk factor for OSA. It certainly matters. But several large datasets have made something very clear: a substantial share of adults with OSA are not obese.

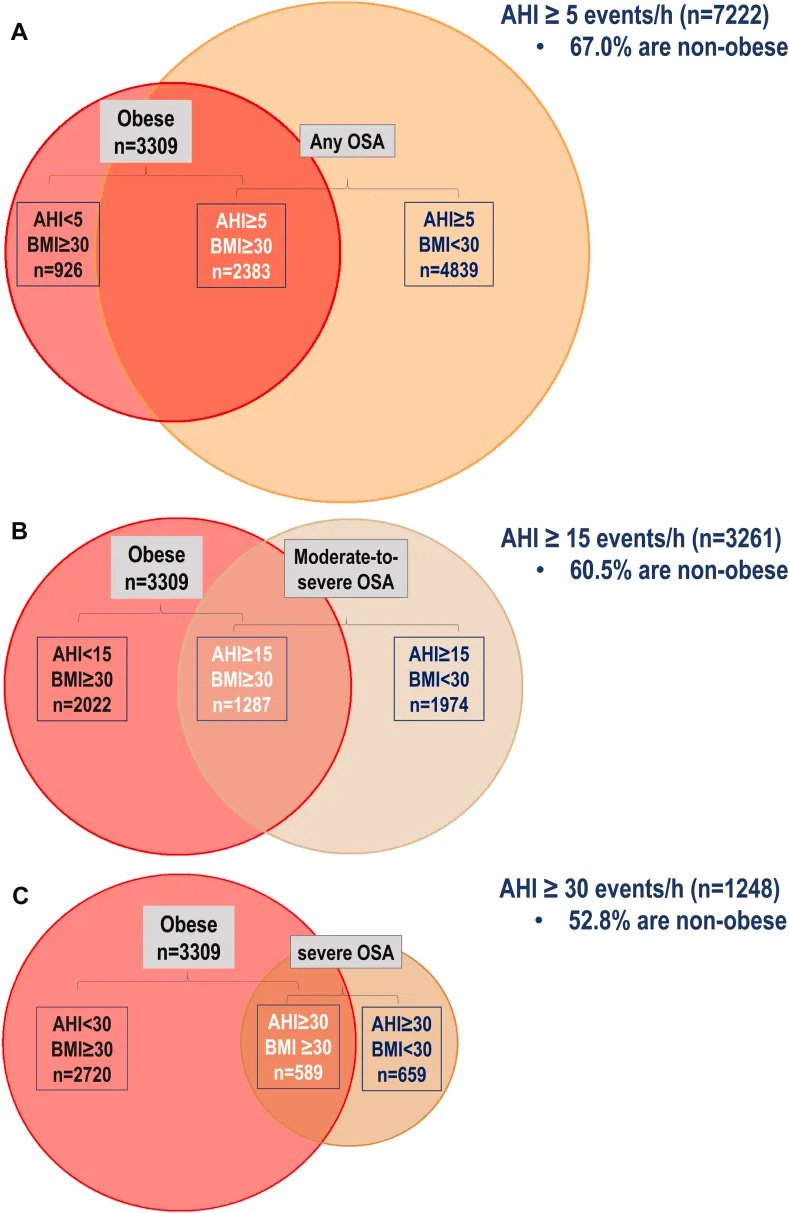

In a large community-based cohort of nearly 3,000 adults with OSA, the median BMI was just under 29, and about 60% had BMI below 30, meaning they were not in the obese range. A more recent individual-participant meta-analysis of over 12,000 adults found similar patterns: the majority of people with OSA were either overweight or of normal weight; only a minority had obesity.

Another clinical series looked specifically at adults with OSA but no obesity. This group made up a substantial proportion of referrals. They tended to have different underlying drivers (for example, a very sensitive arousal threshold or airway shape issues rather than pure weight-related narrowing), and they were harder to treat with standard CPAP, with lower adherence.

The take-home is this:

you can be a fit, non-obese, health-conscious 55-year-old and still have sleep-disordered breathing that matters. Weight is just one risk factor.

How OSA changes with age: Obstructive sleep apnea is not one static disease

- In younger, heavier adults, the airway problems are often driven by soft-tissue bulk and anatomy. The airway can collapse completely. You see large obstructive apneas, big drops in oxygen, loud snoring, and very obvious events on a sleep study.

- In many older or non-obese adults, muscle tone decreases and control of breathing becomes more fragile. Rather than dramatic collapses, you see partial narrowing of the airway, with harder work of breathing, subtle restriction of airflow (often called flow limitation), and frequent brief awakenings as the brain keeps rescuing you. Oxygen levels may dip only slightly. On paper, the study can be described as “mild” or even “normal”, but subjectively, sleep feels broken.

Instead of a few big events, you get countless small stutters. Even if each one looks minor, the cumulative effect can be a night of severely fragmented sleep.

This shift with age is one reason I listen carefully when a midlife patient says: “I don’t snore that badly, but I never feel like I get into deep sleep.” It doesn’t prove sleep-disordered breathing is present, but it keeps the door open to that possibility—even when BMI and laboratory tests look reassuring.

More on “OSA” representing many different phenotypes: Two people can have the same AHI and very different physiology.

Some patients have strongly anatomical disease: a smaller lower jaw, a crowded tongue space, or other structural narrowing that makes the airway prone to collapsing. Others have airways that are adequate on exam, but their brain’s control of breathing is highly sensitive (high “loop gain”), so small fluctuations in CO₂ lead to overshooting and undershooting of breathing. Some wake very easily with the slightest restriction in airflow (a low arousal threshold), while others sleep through far more marked events.

Events can also cluster

Some people have supine-predominant OSA, where breathing is much worse on their back, and much better on their side. Others have REM-predominant OSA, where events are concentrated in rapid eye movement sleep.

All of these variants can yield similar AHIs. An AHI of 8 in someone who snores loudly, feels fine, and has calm overnight oxygen traces is a different problem than an AHI of 8 in someone who is exhausted, foggy, and clearly distressed by their sleep. A single number does not capture that difference.

Why AHI can mislead

The apnea–hypopnea index captures how many times per hour your breathing crosses certain thresholds of reduction in airflow and duration. It is an event-counting tool. That is useful, but it has blind spots.

AHI does not directly tell you:

- how often your brain is being jolted into lighter sleep

- how long each event lasts

- how much extra effort you are putting into each breath during partial obstruction

- how active your sympathetic (“fight or flight”) nervous system is overnight

It is possible to have a “normal” or “borderline” AHI while your sleep is being fragmented by subtle, effortful breathing over and over again.

Clinically, this often shows up in two overlapping ways.

Upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) and flow limitation

One pattern is sometimes labelled upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS). In UARS, the airway repeatedly narrows enough to make breathing harder and to trigger micro-arousals, but not enough to meet the standard scoring criteria for apnea or hypopnea. Oxygen levels usually stay near normal. AHI is often under 5, which puts you in the “no OSA” box by traditional rules.

Yet people with UARS frequently describe unrefreshing sleep, daytime fatigue, and “tired but wired” nights. In a study that compared patients with UARS to patients with mild OSA and to healthy controls, the UARS group actually reported worse sleep quality, more fatigue, and poorer early-morning attention than those with mild OSA, despite having a lower AHI.

Another related concept is flow limitation itself. Rather than looking only at events that meet the thresholds for apnea or hypopnea, you look at periods when airflow is clearly flattened or restricted, indicating that the upper airway is narrowed and breathing is more effortful.

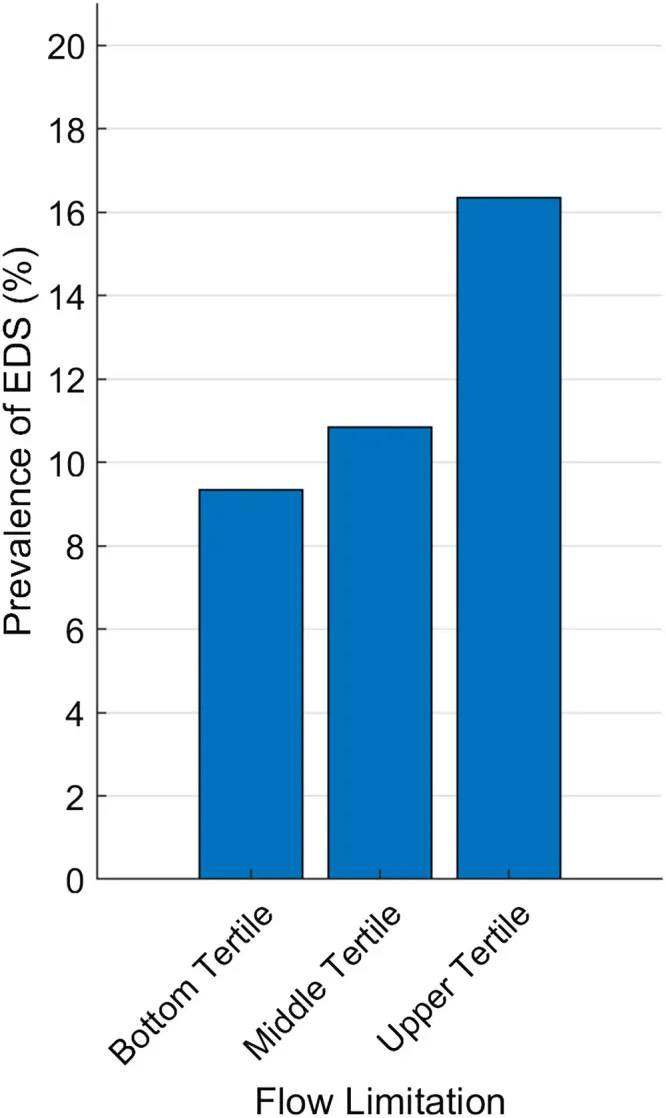

A 2024 study in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society focused on adults with AHI under 15—so no moderate or severe OSA by the usual scale. Within this “low-AHI” group, the researchers asked whether the amount of flow limitation mattered. They found that as flow limitation increased, the odds of excessive daytime sleepiness doubled, even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, ethnicity, sleep duration, and AHI itself.

Put simply:

You can have an AHI that looks reassuring on the report and still have enough disrupted breathing to leave you sleepy and impaired during the day.

When numbers and lived experience disagree

This is often where people feel unheard. They have done their homework. They have reduced caffeine, gone to bed more consistently, worked on their sleep environment, and tried to manage stress. They are doing the things any sensible clinician would advise.

They then have a sleep study which returns with an AHI of 2.8 or 4.3 and a comment like “no significant sleep apnea.” On paper, they are fine. In their body, they are not fine.

In my practice, I talk about 3 pillars that guide whether we consider treatment:

- Objective risk. If the AHI and oxygen patterns clearly fall into a range known to increase cardiovascular and metabolic risk, that carries weight.

- Impact on others. Loud snoring, gasping, or frequent awakenings can disrupt partners and family, and sometimes that alone motivates change.

- Symptoms and function. If daytime performance, mood, and quality of life are meaningfully compromised, and other obvious causes have been addressed, that matters even when AHI is modest.

When all three point in the same direction, decisions are straightforward. When AHI looks “mild” or “borderline” but symptoms are severe, I am less interested in debating whether the label is OSA, UARS, or “just poor sleep,” and more interested in understanding the pattern and deciding whether targeted treatment might help.

The studies on non-obese OSA, UARS, and flow limitation are helpful here because they back up what patients have been saying for a long time: a single index can underestimate how disruptive their sleep-disordered breathing really is.

Once you step away from treating AHI alone, treatment becomes a question of what is actually driving the problem in this particular person.

That includes the obvious anatomy—jaw size, tongue space, nasal obstruction, tonsils and palate—but also how sensitive the brain’s control of breathing is, how easily the sleeper wakes up when breathing becomes a little harder, and whether events cluster when on the back or in REM sleep. It also includes everything that sits “around” the airway: insomnia patterns, evening alcohol, medication timing, underlying mood and anxiety conditions, circadian rhythm shifts, and so on.

This is why two 60-year-old non-obese patients with the same AHI can end up with different plans. One person’s airway may be particularly vulnerable when they lie on their back, so positional therapy and nasal work could make a large difference. Another might have jaw-related narrowing and respond well to a properly fitted oral appliance. A third might genuinely need CPAP as the backbone of treatment because of event severity or oxygen drops, even if they look “fit.”

The point is not that AHI is useless; it is that it is only one lens. The more we understand the underlying pattern, the more we can match treatment to that pattern rather than forcing every square peg into the same round hole.

Beyond CPAP: a brief map of options

CPAP remains the standard treatment for moderate to severe OSA, and a trial can be useful even for people in the gray zones to see whether stabilizing breathing reduces symptoms. But it is not the sole option, especially for milder or phenotype-specific patterns.

For midlife patients, the conversation I have most often sounds like this:

“Your study doesn’t show severe obstruction, but you have a pattern that is very likely contributing to the way you feel. Let’s talk about what we can adjust and what we can support.”

Depending on anatomy, symptoms, and preferences, that might include:

1. Jaw-based and positional strategies

- Mandibular advancement devices made by a qualified dentist, which gently move the lower jaw forward to widen the airway.

- Positional therapy devices or methods, when events cluster almost entirely on the back and nearly vanish in side-sleeping positions.

2. Nasal and airway support

- Addressing nasal obstruction with saline rinses, medicated sprays, or structural procedures when indicated.

- Occasionally adding myofunctional (orofacial) therapy to improve muscle tone and tongue posture as an adjunct, not a stand-alone fix.

3. Whole-sleep context (would add 4. Potential surgical options) can leave it at that and not discuss the full listing or say something about how my newsletter expounds more on all the various options and risks/benefits, and where they might fit in.

- Targeted insomnia treatment (often CBT-I) when difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or early wake-ups coexist with mild breathing disturbance.

- Hormone support where appropriate (for example, perimenopause/menopause or testosterone changes that interact with stress tolerance, autonomic regulation, sleep quality, and airway stability).

- Circadian alignment: consistent timing, morning light, and a stable anchor for the wake-time so the brain knows when deep sleep is supposed to happen.

- Medication review to identify substances that worsen breathing stability or fragment sleep.

4. Potential surgical options

Surgical therapies for OSA broadly fall into several categories:

- Nasal Surgery

- Palatal Surgery

- Tongue Base and Hypopharyngeal Surgery

- Skeletal Surgery

- Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulation

For details on the risks benefits and where they may fit your situation, you can check out the Sleep Docs publication here.

For someone who does not fit the classic snoring stereotype, we often end up combining a modest airway intervention with focused work on insomnia, hormoal, circadian cues, and autonomic load. The goal is not to “treat an AHI,” it is to restore the person’s ability to wake up feeling like sleep did its job.

What you can do next

If this all sounds familiar—if you don’t fit the classic picture of sleep apnea, your test was labelled “normal” or “borderline,” and you still feel unrefreshed—there are concrete steps you can take.

- Look at your report, not just the summary.

Check whether your study commented on arousals, flow limitation, respiratory effort–related arousals (RERAs), or positional / REM-predominant patterns, not just the AHI.

- Bring your symptoms into the foreground.

When talking with a clinician, describe how your sleep and days actually feel: unrefreshing sleep, brain fog, mood changes, headaches, morning dry mouth, nocturia, or anything else that stands out. These help frame whether “mild” numbers are truly mild for you.

- Ask explicitly about non-obese and low-AHI patterns.

It is reasonable to ask whether upper airway resistance, frequent arousals, or flow limitation might be part of the picture even if you do not have obesity and your AHI is under 5 or in the mild range.

- Consider a second opinion with someone who routinely sees non-obese OSA.

An ENT or sleep physician who is comfortable with UARS, flow limitation, and phenotype-based treatment can often add nuance beyond “yes/no apnea”.

- Think in terms of trials.

Whether it is a positional device, an oral appliance, a period of CPAP, nasal treatment, or a structured insomnia programme, it is reasonable to try an intervention for a defined period and see whether your sleep and days feel meaningfully better.

The core message is that numbers and lived experience both matter.

AHI is a useful starting point, but it does not have the final word—especially for non-obese, midlife adults whose sleep feels broken despite being told it is “normal”. If that is you, it is not unreasonable to keep asking questions until the story in your body and the story on the report line up.

If you are in midlife and feel chronically unrefreshed, do not let a borderline-sounding report close the chapter.

Sleep-disordered breathing can present in many ways.

AHI can underestimate the burden in people whose main problem is flow limitation and sleep fragmentation rather than dramatic apneas and desaturations. Phenotype work shows that different clusters of symptoms and traits behave differently and respond to different treatment mixes. Residual sleepiness research tells us that even when airway treatment is optimized, other contributors often need to be addressed explicitly.

The practical takeaway:

- Your lived experience matters as much as the line on the report.

- If your symptoms and your study don’t seem to match, it is reasonable to seek a second look from someone who is comfortable thinking beyond AHI alone.

- Treatment conversations can and should extend past “CPAP or nothing,” especially in midlife adults who don’t fit the classic mold.

Listening carefully to symptoms, reading the sleep study in that context, and using the full toolbox of airway and non-airway interventions is how we start to close the gap between “your numbers look fine” and “you feel like yourself again.”

—Chris Gouveia & Kat Fu

P.S. If you’ve ruled out apnea and are still struggling with sleep — especially waking at 3 a.m. or sleeping 5-6 hours no matter what you try — that’s what I spend most of my time helping individuals with. Start here:

References

- Gray EL, McKenzie DK, Eckert DJ. Obstructive Sleep Apnea without Obesity Is Common and Difficult to Treat: Evidence for a Distinct Pathophysiological Phenotype. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 Jan 15;13(1):81-88. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6394. PMID: 27655455; PMCID: PMC5181619.

- Esmaeili N, Gell L, Imler T, Hajipour M, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Stone KL, Sands SA, Ayas N, Yee J, Cronin J, Heinzer R, Wellman A, Redline S, Azarbarzin A. The relationship between obesity and obstructive sleep apnea in four community-based cohorts: an individual participant data meta-analysis of 12,860 adults. EClinicalMedicine. 2025 Apr 23;83:103221. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103221. PMID: 40330547; PMCID: PMC12051718.

- Mann DL, Staykov E, Georgeson T, Azarbarzin A, Kainulainen S, Redline S, Sands SA, Terrill PI. Flow Limitation Is Associated with Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Individuals without Moderate or Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024 Aug;21(8):1186-1193. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202308-710OC. PMID: 38530665; PMCID: PMC11298983.

- de Godoy LB, Luz GP, Palombini LO, E Silva LO, Hoshino W, Guimarães TM, Tufik S, Bittencourt L, Togeiro SM. Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome Patients Have Worse Sleep Quality Compared to Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea. PLoS One. 2016 May 26;11(5):e0156244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156244. PMID: 27228081; PMCID: PMC4881892.

- Harvard Sleep Medicine. Sleep apnea: Understanding your sleep study and AHI categories.