Your Brain Makes Its Own Sleep Drug—And It’s More Sophisticated Than Valium: progesterone for sleep

Millions of adults struggling with sleep—including myself—have, at one point or another, turned to sleep medications.

The hope being, to bring relief through better rest that would also safeguard our cognitive health.

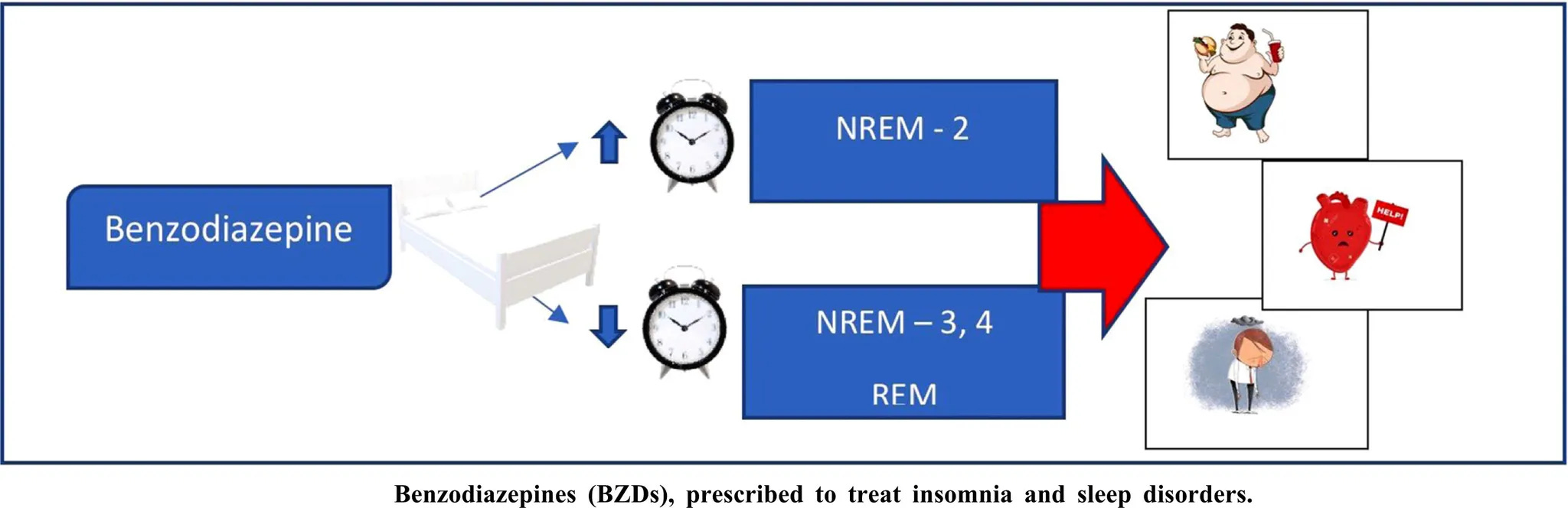

But a 2025 study published in Sleep, found that long-term benzodiazepine use is instead linked to poorer sleep quality through disruptions in both macro and micro-architectural sleep patterns.

Participants in the treatment group experienced “lower N3 and higher N1 duration and spectral activity and altered sleep-related brain oscillations synchrony”—Barbaux, et al., Sleep, 2025

The authors further hypothesized that these are also architecture changes that contribute to reported associations between use of this class of sleep aids and cognitive impairment in older adults.

Yet, what many of us don’t realize is that the brain produces its own sleep molecule.

And in many ways, it is more sophisticated than prescription sleep aids.

That compound is allopregnanolone, a metabolite of progesterone —a hormone produced by both women and men.

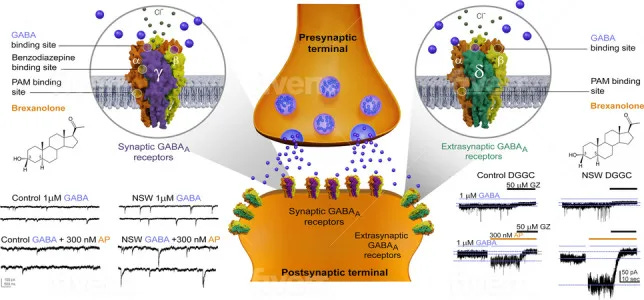

Allopregnanolone acts on the same GABA-A receptors targeted by drugs like Valium, but with a “broader reach” that includes receptor sites benzodiazepines do not affect.

To see why this difference matters for our brain health & sleep, we first need to look at how benzodiazepines work:

By the way, If you’ve been following my work on hormones and sleep, you’ll know how much depth there is beneath the surface.

If you’re ready to go deeper and take a systems-based approach to improving your sleep, Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

or

How Benzodiazepines Work—And Why They Fall Short

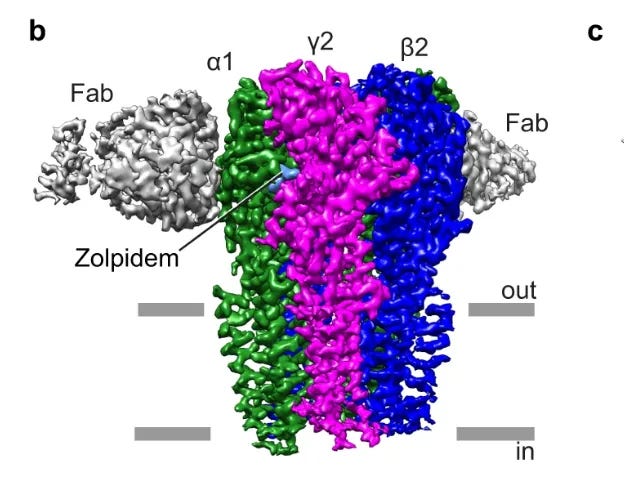

Benzodiazepines act only on certain GABA-A receptors—namely, those containing the γ2 subunit and a compatible α subunit.

These receptors are clustered at synapses, where nerve cells communicate directly. Their job is to produce phasic inhibition: short, powerful bursts that silence an overactive circuit for a moment.

You can think of it as flicking a switch on and off.

That sharp action produces sedation.

But sedation is not the same as natural sleep.

Across studies, benzodiazepines, reduce slow-wave activity (N3), reduce REM time, and as a result, mornings may feel less restorative.

Individuals who have used these medications describe the effect in lived terms: “It feels like sleep from alcohol—lighter, less restorative,” or, “I don’t like the way it leaves me feeling afterward.”

In essence, sleep induced by medications can be unsatisfying as the brain is sedated, but isn’t guided through its natural architecture of deep and REM stages.

This now raises an important question: if the brain’s own sleep molecule works on the same receptor family, how does it avoid these problems?

What Makes Our Brain’s Own Sleep Molecule More Sophisticated?

The brain’s own sleep molecule, allopregnanolone, acts differently.

Allopregnanolone works on the same GABA-A receptor family as benzodiazepines, but it doesn’t stop at the γ2 sites. Instead, it also acts on extrasynaptic receptors (δ-containing sites)—locations outside the synapse that respond to ambient levels of GABA in the brain.

These extrasynaptic sites generate what scientists call tonic inhibition: a steady, background current that calms whole networks rather than just flicking individual switches.

The lived effect is therefore very different.

Rather than the disjointed sedation, we can experience smoother transitions between stages, fewer abrupt awakenings, and the continuity of the natural rhythm of sleep.

And There Is Another Difference With Sleep Medications—One That Becomes Especially Important With Age

These sleep medications can suppress ventilatory drive and can worsen sleep-disordered breathing in susceptible individuals (e.g., those with obstructive sleep apnea), with higher risk of acute respiratory failure reported.

By contrast, progesterone and its metabolite allopregnanolone can support brainstem circuits involved in stabilizing breathing rhythms through the night.

Taken together, these 3 actions:

- Synaptic calming

- Extrasynaptic network stability

- Ventilatory drive support via progesterone (with allopregnanolone modulation of respiratory networks)

—show how allopregnanolone can help preserve both sleep architecture & physiological steadiness in a more “sophisticated” way than sleep medications.

So, Where Does Allopregnanolone Come From?

Allopregnanolone is not produced in isolation.

It is converted from the hormone progesterone—most widely known as the “pregnancy hormone.”

But does this mean it only matters for women, or only during pregnancy?

The answer carries implications for anyone struggling with sleep.

Regardless of whether you are a woman or a man, progesterone—produced from multiple sources in the body—feeds the brain’s production of allopregnanolone.

This article will show you how that process works, and why it matters for sustaining restorative sleep as you age—even if reproductive hormones have declined, and conventional sleep recovery approaches have not worked.

Here’s what you’ll walk away with:

- Who produces progesterone (the precursor to allopregnanolone): Why it isn’t just a “women’s hormone”.

- Where production occurs: The 3 sources that feed the brain’s sleep-supporting allopregnanolone.

- What a 2024 Harvard study revealed: A newly discovered allopregnanolone production pathway—one that expands how we can approach sleep recovery in aging.

- The emerging frontier for sleep? Why targeting this axis could become more important than traditional hormone approaches as we age—and what this means for personalized strategies.

Let’s get started.

Section 2: Progesterone Is Not Just A “Women’s Hormone”

Both men and women produce progesterone across the lifespan, and both rely on it as a precursor to allopregnanolone.

The most familiar source is a woman’s ovaries.

But men also produce progesterone in the testes.

Women’s Ovarian Production

During reproductive years, the ovaries are the dominant source of progesterone. After ovulation, the follicle transforms into the corpus luteum, generating surges that can raise progesterone levels tenfold compared to earlier in the cycle. These fluctuations feed into the brain’s neurosteroid pool, which is one reason why many women notice changes in sleep quality across the cycle.

Men’s Testicular Production

Men also produce progesterone, though few realize it. In the testes, progesterone serves mainly as an intermediate in testosterone synthesis. While most is converted to testosterone, some remains available to cross into the brain for conversion into allopregnanolone. Male sleep is therefore influenced more by the steadiness of this background output.

These reproductive sources are important in early and midlife, but they decline with age. After menopause, ovarian progesterone output declines sharply. In men, testicular supply also diminishes gradually with age.

But there are positive aspects to consider.

Progesterone production is not limited to reproductive organs. Other production sites continue to maintain output on a steadier basis.

Where, then, does production continue after reproductive transitions?

Section 3: Progesterone Is Not Just A Reproductive Hormone

Here are 2 of the alternative sources that maintain progesterone supply (and thus allopregnanolone):

Adrenal Production

The adrenal glands are two small structures that sit on top of the kidneys.

They are best known for releasing cortisol and adrenaline during stress, but they also produce progesterone.

Unlike ovarian or testicular production, adrenal output is not tied to reproductive cycles.

- In women, adrenal progesterone is overshadowed by ovarian surges before menopause, but becomes the main systemic source in later life.

- In men, the adrenals are the dominant source throughout life, with the testes providing a secondary contribution.

Adrenal production has both strengths and vulnerabilities.

Its independence from reproductive status means it can maintain output when other sources decline.

Yet because adrenal function is closely linked to stress response, chronic stress can reduce the efficiency of steroid production over time.

This brings us to the brain—an even more direct source of supply.

If you’ve already tried light, magnesium, or caffeine limits, subscribe for the deeper insights that can help you with sleep:

Brain Production

Unlike adrenal production, which is stress-sensitive, the brain maintains an autonomous supply within brain circuits.

Neurons and glial cells contain the full set of enzymes needed to convert cholesterol into progesterone, and then into allopregnanolone. This supply reaches the brain regions that govern sleep, including the thalamus, hippocampus, and brainstem.

Because brain synthesis functions independently of reproductive or adrenal sources, allopregnanolone production continues even when circulating progesterone levels fall.

This capacity explains how sleep continuity remains possible to us all.

It represents a resilience mechanism available at any life stage. Supporting this local synthesis therefore offers an actionable pathway to maintain sleep quality, even when other hormone systems begin to shift.

That broader perspective sets up the first practical takeaway…

Section 4: Our Sleep System Has Multiple Backup Plans

Sleep stability emerges from several interconnected pathways—each contributing to the brain chemistry that supports sleep.

Across the lifespan, the relative importance of each pathway shifts.

The empowering reality is sleep stability remains achievable across different life stages.

What makes this even more encouraging is the sophistication of the compound itself—creating natural sleep architecture rather than pharmaceutical sedation, while maintaining this production resilience across multiple sources.

Rather than accepting fragmented sleep as inevitable, targeted approaches can effectively work with these existing alternative pathways. It’s not about preventing all changes—it’s about recognizing which production routes remain available and can be supported.

But even with these coordinated networks, the picture is not yet complete.

Not sure if hormones are part of your sleep disruption?

Sleep OS Hormones helps you find out.

Testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone imbalances can each fragment sleep in different ways—through conversion, clearance, or receptor sensitivity as much as production. Sleep OS Hormones shows you how to recognize hormone-related patterns, even if you don’t have labs.

In 2024, Harvard researchers discovered another source of allopregnanolone production—functioning outside the traditional hormone pathways—that may, remarkably, take on greater importance with age.

That is where we turn next.

Section 5: The Microbiome: A Newly Described Source of Allopregnanolone

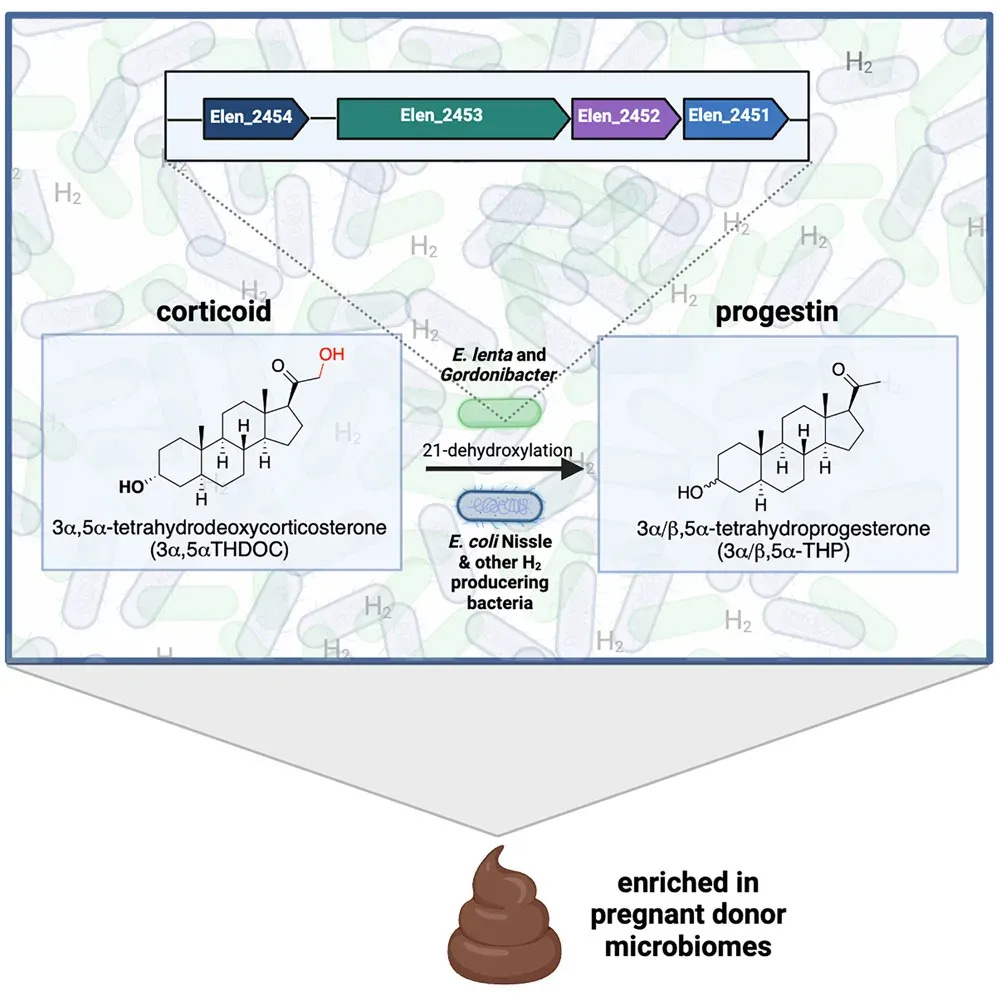

In 2024, Harvard researchers reported in Cell Press that the gut itself can act as a factory for allopregnanolone. Specific microbes carry enzymes that allow them to convert certain precursors into this same sleep-supporting compound.

Two groups—Eggerthella and Gordonibacter—were identified as carrying the necessary enzymatic steps. Others, such as Clostridium scindens, create the right metabolic environment for the conversion to occur.

💡 In plain terms: alongside the ovaries, testes, adrenals, and brain, the gut can now be considered another source of allopregnanolone.

Together, these organisms form a cooperative network capable of producing allopregnanolone inside the intestinal tract.

Why This Matters for Sleep Architecture in Aging

The allopregnanolone produced through this microbial pathway has the same biological signature as the compound described earlier.

💡 Allopregnanolone acts on extrasynaptic GABA-A receptors containing δ subunits, which generate the steady background current that helps maintain sleep continuity & reduce middle-of-the-night awakenings.

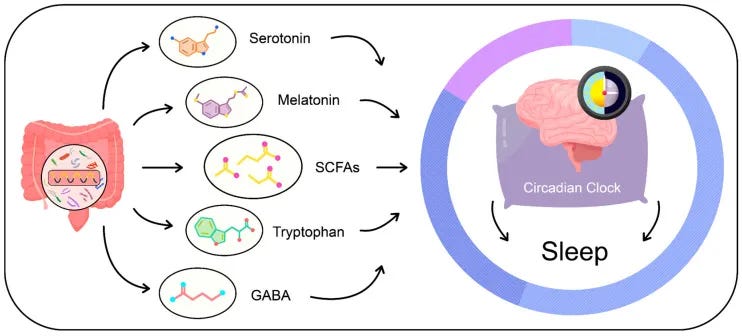

While it is not yet clear whether gut-derived allopregnanolone enters human circulation, there are two plausible routes by which it could still influence sleep:

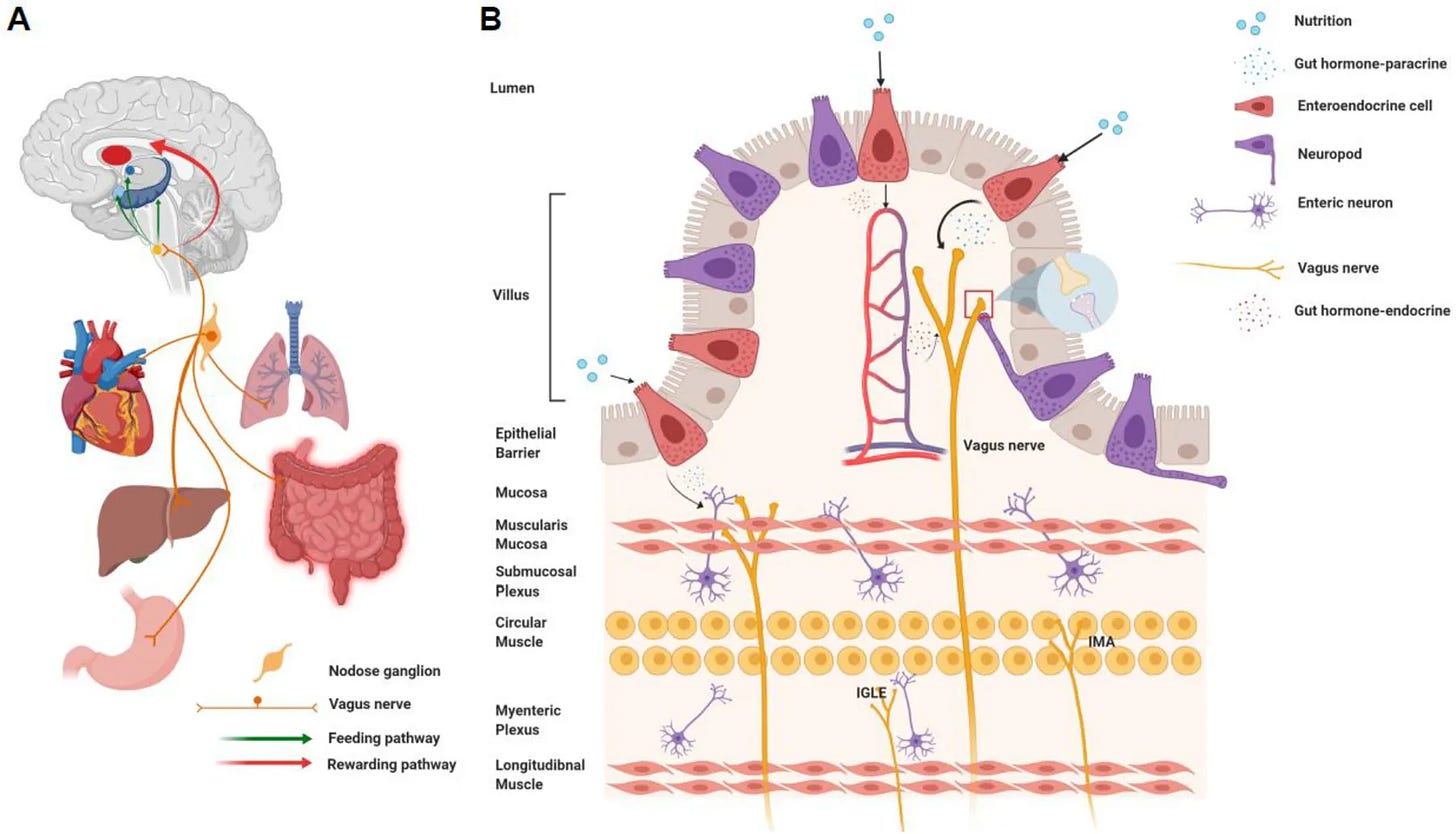

- Local signaling. Both GABA-A and NDMA receptors are present on vagal afferents, meaning that compounds produced in the intestinal wall may act locally while transmitting effects to the brain via gut–brain pathways. A similar principle is seen with gut-derived serotonin, which can influence brain function via local/paracrine/vagal routes without necessarily depending on bloodstream levels.

- Circulatory precedent. Intestinal melatonin has been shown to enter circulation and contribute to plasma concentrations, raising the possibility that other gut-derived compounds could follow a similar route.

What makes this pathway distinctive is its potential adaptability.

Because it depends on microbial diversity and nutrient availability, it is more directly open to influence. While brain production can be supported through broader resilience strategies, gut production can be potentially shaped more dynamically through diet, microbial inputs, and substrate supply.

This adaptability raises an intriguing possibility: if the gut can produce allopregnanolone and communicate directly with the brain, could optimizing the gut-brain connection become a new frontier for sleep support?

Section 6: Is the Gut–Brain Axis the Next Frontier for Sleep?

The gut is not just a source of compounds—it also communicates directly with the brain.

This bidirectional communication network is becoming increasingly important in sleep science.

Some of these connections were already well established.

- Serotonin made in the gut influences circadian rhythm and mood regulation via vagal, endocrine, and immune routes.

- The vagus nerve provides a direct communication channel from the intestinal wall to the brainstem, carrying chemical messages that can influence brain activity and, by extension, sleep–wake regulation.

- Immune signaling adds another layer, as microbes shape cytokines such as IL-6 that are bidirectionally linked with sleep drive and fragmentation in both experimental and clinical contexts.

The discovery of gut-derived allopregnanolone adds a new dimension.

Unlike serotonin or melatonin, which influence sleep indirectly through circadian timing and mood, allopregnanolone strengthens the inhibitory tone that helps maintain sleep continuity.

The gut has therefore evolved from a digestive organ to a recognized partner in sleep regulation, with new mechanisms still being discovered.

Seen through this lens, the gut–brain axis broadens how we understand sleep resilience—

Differences in sleep quality with age are not only about what declines—they are also about which signaling routes remain active.

For those working to sustain deep, restorative sleep, this broader map shows there are more pathways to support than we once realized.

Rather than relying on a single approach, we can now work with multiple biological systems—each offering distinct opportunities to maintain the sophisticated sleep chemistry our brain produces naturally.

When It Comes to Hormones & Sleep, It’s Not Just About Hormone Production

In this article we’ve focused on progesterone—how its production and conversion into allopregnanolone provides a sleep molecule the brain makes for itself.

But hormone function is never just about production levels.

It’s also about metabolism, receptor sensitivity, hormone utilization, transport, conversion pathways, clearance, etc. —different factors become more relevant for different hormones.

This complexity is why sleep can be unstable even when hormone lab levels look normal.

And it’s also why many individuals who take supplemental hormones don’t experience the benefits on sleep they expect—because hormone supplementation/replacement alone doesn’t address these downstream steps.

Instead of taking a trial-and-error approach to which factors matter most for your individual hormone patterns, this complexity is what Sleep OS Foundation Hormones addresses.

Are Hormones Affecting Your Sleep?

Sleep OS: Hormones helps you to optimize your hormone function for restorative sleep through:

- Recognition Patterns That You Can Start With Immediately. Many people aren’t sure if hormone function is part of their sleep disruption. Sleep OS helps you identify which hormone patterns may be affecting your sleep—with signs that point to testosterone, estrogen, or progesterone involvement in sleep disruption.

- Risk Group Assessment. Who is more likely to experience hormone-related sleep issues based on life stage, stress patterns, and other factors. For example, testosterone alone has 5 risk categories for men, 5 for women, plus 9 additional categories that apply regardless of gender. Age is a factor, but not the only one.

- Lab-Free Approach That Addresses Testing Limitations. Standard hormone blood tests show levels at one moment and miss metabolism patterns. Advanced hormone testing like DUTCH panels ($400+) adds metabolite analysis, but even DUTCH lab testing can’t address receptor sensitivity, transport efficiency, or cellular utilization—factors that determine whether hormones can be used. If you already have labs, you can layer them in to refine your approach, but they are not required.

- Safe, Structured, Self-Help Strategies. Rather than requiring testing or recommending hormone supplements, Sleep OS Foundation: Hormones provides evidence-based & self-help approaches that can work alongside hormone supplementation if you’re already using it, or independently if you prefer non-pharmaceutical support.

- Beyond Production Focus. While most hormone approaches focus solely on hormone levels, Sleep OS Foundation: Hormones addresses the full cascade—because even optimal production won’t improve hormone function if utilization is compromised.

Who Is Sleep OS Foundation: Hormones For?

Sleep OS Foundation: Hormones is for anyone whose nights are shaped by more than bedtime routines—including those who aren’t sure yet whether hormones are part of the problem but want to find out.

It’s built for:

- later-decade hormone changes,

- chronic stress, or

- health-aware individuals who have already optimized lifestyle factors but still find their sleep unstable

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

P.S. Hormones & sleep aren’t just about being “too high” or “too low”—and they’re not limited to one gender or life stage. I recently broke down 4 common misconceptions about how hormones affect sleep.

References

- McCurry MD, et al. Gut bacteria convert glucocorticoids into progestins in the presence of hydrogen gas. Cell. 2024 Jun 6;187(12):2952-2968.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.005. Epub 2024 May 24.

- Loïc Barbaux, et al, Effect of chronic benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine receptor agonist use on sleep architecture and brain oscillations in older adults with chronic insomnia, Sleep, 2025.

- Diviccaro S, Cioffi L, Falvo E, Giatti S, Melcangi RC. Allopregnanolone: An overview on its synthesis and effects. J Neuroendocrinol. 2022 Feb;34(2):e12996. doi: 10.1111/jne.12996. Epub 2021 Jun 29.

- Reddy DS, Mbilinyi RH, Estes E. Preclinical and clinical pharmacology of brexanolone (allopregnanolone) for postpartum depression: a landmark journey from concept to clinic in neurosteroid replacement therapy. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2023 Sep;240(9):1841-1863. doi: 10.1007/s00213-023-06427-2.

- Because the reference list is extensive, I’ve compiled the full reference library for this article here for those who want to learn more.

- Li Z, et al. Essential roles of enteric neuronal serotonin in gastrointestinal motility and the development/survival of enteric dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2011 Jun 15;31(24):8998-9009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6684-10.2011.