You already know that sleep is not just about feeling rested.

Poor or fragmented sleep affects memory, mood, blood sugar, blood pressure, and how much reserve you feel you have for the things you care about most. For many, the options that get suggested first are medications or supplements, and movement often does not enter the conversation.

Exercise, however, is one of highest impact health (& sleep improvement) strategy you fully control.

It interacts with your circadian rhythm, your stress response, your muscles, and your brain. It can potentially deepen your sleep, shorten how long you lie awake during sleep, and reduce the emotional “charge” around insomnia.

It also has its own direct links to brain health and dementia risk.

Over just the last few years, research on exercise and sleep has accelerated: large wearable-device datasets, pooled analyses of dozens of trials, and brain-imaging work now give a more 3-dimensional view of how movement interacts with your sleep than we have ever had before.

When you look at this newer research as a whole, every decision to move a bit more becomes a positive step you are taking towards sleeping, thinking, and functioning better in the years ahead.

In this article, we’ll cover

- How different exercise types can influence your sleep quality and sleep structure

- What large, recent pooled data sets suggest about how much & what kind of exercise seems most effective for sleep

- Which exercise modes—can influence brain circuits in a direction that looks more like good sleepers

- What an Alzheimer’s study suggests about exercise and sleep architecture at the level of brain pathology

- Finally, we’ll cover 5 actionable strategies to help you translate all of this into an exercise approach that supports better sleep & more daytime energy.

Let’s get started.

Section 1: Study 1 – 2025 review on best exercise types & doses for sleep

In a 2025 study— researchers pulled together 86 trials where adults were assigned by chance to either an exercise program or a non-exercise comparison (often usual activity or light stretching). They covered 7,276 adults aged 18–75, with a substantial portion in middle and older age.

The programs included brisk walking and cycling (aerobic exercise), resistance training with weights or bands, mixed aerobic plus resistance programs, yoga, Pilates, and traditional Chinese sports such as Tai Chi and Qigong.

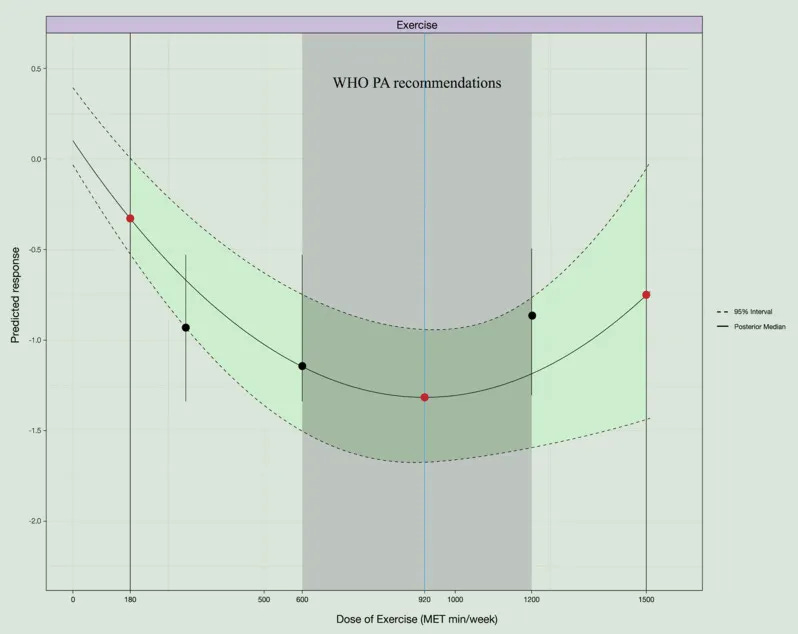

Instead of only comparing one exercise type at a time, the team used a pooled comparison of many exercise types at once (a network meta-analysis). They also modelled how weekly “dose” of movement, expressed in MET-minutes per week (a combined measure of intensity and duration), related to improvements in sleep quality (a dose–response analysis). The main sleep outcome was validated sleep questionnaires such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Key findings for sleep:

- Across all 86 trials and 7,276 participants, every exercise type beat non-exercise controls for sleep quality, with standardized mean differences (a common trial effect-size metric) from about −0.8 to −1.7, which is typically considered a large change in symptoms on a questionnaire scale.

- Ranked probability for an exercise modality to improve sleep in this study (based on SUCRA —Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking curve—a meta-analytic ranking metric)

- Pilates: 91.7% (highest probability of being best for sleep quality)

- Aerobic exercise: 69.7%

- Combined aerobic + resistance training: 59.4%

- Resistance training alone: 58.6%

- Traditional Chinese sports: 40.5%

- Yoga: 30.1% → still beneficial for sleep, but with the lowest probability of being the top choice in this ranking.

- Regarding how much exercise: improvement in sleep quality started to become statistically robust at around 180 MET-min/week of exercise and reached an estimated optimum at about 920 MET-min/week, beyond which gains flattened. At roughly 1,500 MET-min/week, the model suggested a plateau where adding more movement did not provide extra sleep benefit.

- Within the World Health Organization’s recommended range (about 600–1,200 MET-min/week), the predicted effect on sleep quality remained solid.

Taken together, this 2025 work suggests that in midlife and beyond—many styles of movement can meaningfully improve self-reported sleep quality, especially when weekly movement sits in roughly the same energy range that global guidelines suggest.

For you, that might translate to something like 180–260 minutes per week of brisk walking, cycling, Pilates, or similar activities, depending on intensity.

Section 2: Study 2 – 2026 analysis of mind–body and aerobic exercise in midlife and older adults

In 2026, metanalysis asked: do mind–body practices (such as Tai Chi, Qigong, or yoga) and aerobic exercise change both how people feel about their sleep & what devices measure during their sleep?

The authors pooled 28 trials in which middle-aged and older adults were assigned by chance to either a mind–body movement program, an aerobic exercise program, or a control condition (e.g., low-intensity stretching). They looked at subjective scores (PSQI and similar scales) and objective metrics such as total sleep time and wake time after sleep onset from polysomnography or actigraphy.

Key findings:

- Mind–body exercises produced a strong improvement in subjective sleep quality compared with controls, with strong statistical support (P < 0.00001), meaning that participants reported noticeably better sleep after these practices.

- Aerobic exercise also improved subjective sleep quality compared with controls, with P = 0.0001, again indicating a robust change in how people rated their sleep.

- For objective sleep, both mind–body and aerobic exercise increased total sleep time, with pooled analyses showing statistically significant gains (P = 0.004), so people not only felt they slept longer; monitoring devices agreed.

- Both exercise categories reduced wake time after sleep onset (the minutes you are awake during your sleep once you have fallen asleep), with P < 0.00001, suggesting fewer or shorter wakeful stretches. In contrast, estimated sleep efficiency and how quickly people fell asleep did not change enough to reach statistical thresholds.

For a midlife or older adults, this 2026 paper suggests that both moderate aerobic exercise and mind–body practices can potentially help you feel that your sleep is better and help you stay asleep, even if they do not significantly change how fast you fall asleep.

Section 3: Study 3 – 2024 Tai Chi plus resistance training and brain connectivity in insomnia

In 2024, researchers ran a trial that goes deeper into how exercise might help an older brain that is struggling with insomnia.

They recruited adults aged 45–80 with insomnia symptoms plus healthy sleepers. People with insomnia were allocated in sequence into either a 12-week group exercise program or a comparison group.

The exercise program mixed slow, coordinated movement and strength work: Tai Chi-based warm-ups, Chen-style short-form Tai Chi, Tai Chi ball practice, and resistance-training movements with weights or bands. Sessions lasted about an hour, 3 times per week, led by skilled instructors in community settings. The team measured:

- insomnia severity (Insomnia Severity Index, ISI),

- overall sleep quality (PSQI),

- anxiety and depression scores,

- wearable EEG-based sleep staging during the sleep, and

- resting-state brain connectivity with high-resolution MRI.

Numbers that translate this into day-to-day effects:

- In the exercise group, ISI scores dropped by 4.19 points and PSQI by 3.49 points over 12 weeks (P < 0.001 for both), while the waitlist group did not change meaningfully. These movements on the 0–28 ISI and 0–21 PSQI scales are usually considered clinically relevant.

- At 12 weeks, the exercise group had Insomnia Severity (ISI) scores 3.36 points lower and PSQI scores 3.32 points lower than the waitlist group (P = 0.0027 and P < 0.001, respectively), suggesting a group-level advantage beyond placebo expectations.

- Anxiety scores fell by about 6 points and depression scores by about 12 points on standard self-rating scales in the exercise group (both P < 0.001), indicating that mood benefits travelled alongside sleep improvements.

- Objective monitoring suggested a trend toward shorter wake time after sleep onset in the exercise group, although this particular change did not reach statistical thresholds, reminding you that not every sleep metric moved in lockstep.

- At the brain level, exercise restored connectivity between primary motor cortex and cerebellum that was reduced in insomnia. Connectivity changes in this motor network correlated with improvements in ISI scores, with correlation coefficients around r = −0.50 (P ≈ 0.002–0.003); the greater the connectivity normalization, the larger the drop in insomnia severity.

For you, this study suggests that a 12-week program mixing Tai Chi-like movement and resistance training can potentially ease insomnia symptoms and quiet the emotional “background noise” of anxiety and low mood, while at the same time nudging motor-network connectivity in a direction that looks more like good sleepers.

Section 4: Study 4 – 2025 Alzheimer’s mouse study on exercise, circadian rhythms, and sleep

To understand how exercise might interact with circadian timing and sleep architecture at the level of pathology, a 2025 paper in Alzheimer’s & Dementia—by National Institute on Aging— used a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (APP^SWE/PS1^dE9 mice). These mice show disrupted sleep–wake patterns, disturbed circadian rhythms, and build-up of amyloid and abnormal tau in brain regions that regulate timing and memory.

Researchers gave these Alzheimer’s-model mice access to voluntary running wheels for two months, while comparison groups included genetically similar mice without running wheels and healthy wild-type mice with or without running.

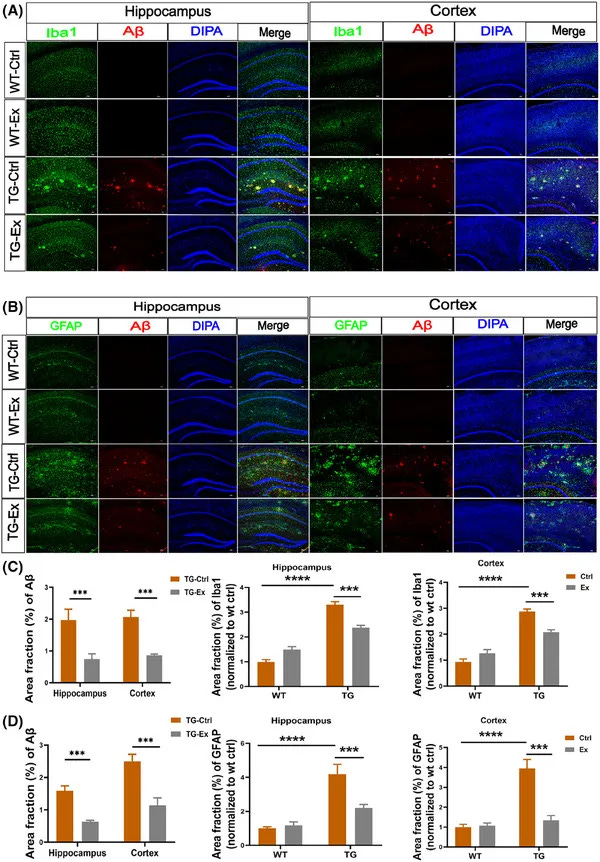

They then measured sleep stages using EEG, circadian behavior across the light–dark cycle, brain expression of clock genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (the brain’s master clock), and structural markers such as amyloid, tau, and glial activation, along with cognitive performance in memory tasks.

Key results that map onto sleep and brain function:

- After two months of voluntary wheel running, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep increased by 89% in the Alzheimer’s-model mice compared with sedentary Alzheimer’s-model controls, indicating a large change in the most dream-rich sleep stage.

- Core clock proteins in the master clock region shifted:

- BMAL1 and RORα protein levels fell by about 45.7% and 36.4%, while REV-ERBα nearly doubled (up 119%) in the suprachiasmatic nucleus.

- At the messenger-RNA level in the hypothalamus, Bmal1 and Rorα dropped 57% and 68%,

- Rev-erbα rose 79%, suggesting a broad recalibration of circadian timing machinery.

- Tau pathology and inhibitory neurotransmission markers in the master clock region changed in a favorable direction:

- phospho-tau 231 levels decreased by 35%, and

- vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) increased by 38.7%, consistent with less tau-related damage and better inhibitory control.

- In hippocampus and cortex, the study shows statistically significant reductions in inflammatory and Alzheimer’s-related markers (Iba1, GFAP, amyloid-β, and phospho-tau 231), alongside better performance in memory tests such as the Morris water maze.

This 2025 animal work cannot tell you directly what will happen in a human brain, but it does suggest that sustained, voluntary aerobic movement can potentially retune circadian timing, restructure sleep architecture (especially REM), and reduce Alzheimer’s-type pathology and neuroinflammation in brain regions that matter for healthy sleep and memory.

Section 5: How to use this: 5 exercise strategies to help your sleep

Bringing these four studies together, you can start to see a pattern: sleep in midlife and later life is movable in ways that can deepen your sleep, help you stay asleep more consistently, and leave you more restored when you wake.

The right mix of type, dose, and consistency can change both how you sleep and how your brain supports that sleep.

Here are 5 action steps grounded in the evidence above—steps you can start today to support deeper sleep, sharper thinking, steadier energy, and the kind of brain health that compounds across the decades ahead: