Benadryl for sleep: Long-term risks and better next steps

I’ve been taking Benadryl every night for ~3 years now. It’s the only thing that knocks me out. Is it bad?”

This question appeared in my inbox recently, and variations of it come up often. The person mentioned some lingering grogginess in the morning, but otherwise assumed everything was fine.

If some version of that lives in your head, you are not the only one. Millions of adults use over-the-counter antihistamines as a regular sleep aid.

The reasoning makes sense: it’s available without a prescription, it’s affordable, and it does produce sleepiness.

On the surface, it looks like a small trade: a familiar allergy ingredient, a predictable sedative effect, and side effects that look like “a little groggy” or “weird dreams.”

This article is about what sits underneath that trade:

- The underappreciated risks that go beyond next-day drowsiness.

- Why long-term use matters for brain health and dementia risk.

- How these drugs disrupt your sleep architecture—even when they help you stay asleep.

- How to think about your next step in a way that matches the complexity of your midlife physiology, instead of just asking, “What else can I take?”

Let’s get started.

Section 1: What OTC Sleep Aids Are and How They Work: is Benadryl safe for sleep every night

When someone says “I take Benadryl for sleep,” they are often referring to a cluster of products:

Benadryl, Advil PM, Tylenol PM, many store-brand “PM” pain relievers, and cold-and-flu combinations.

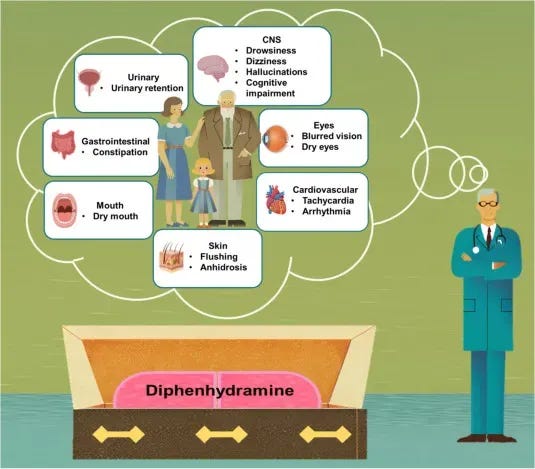

The sedating compound is typically diphenhydramine (Benadryl known) or doxylamine succinate, first-generation antihistamines originally developed for allergies and dermatitis.

The Benadryl side effects you probably recognize: Benadryl for sleep

When you take them for sleep, they:

- Cross into the brain and dampen histamine-linked wakefulness.

- Produce “knocked out” feeling.

- Dry out mucous membranes (dry mouth, dry eyes).

- Slow gut movement and make it harder to fully empty the bladder.

Many who use diphenhydramine regularly are familiar with these side effects. These are common enough that many users consider them acceptable trade-offs.

But, there is also a safety side.

Benadryl slows reaction time, coordination, and decision-making: Benadryl fall risk older adults

A U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report for a 2022 crash cited research showed that a single dose of diphenhydramine impaired driving ability more than a blood alcohol concentration of 0.10 g/dL—above the legal limit for drunk driving in many places.

The cognitive and motor impairment affects activities that require balance & coordination: driving, climbing stairs, getting up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom (through their effects on the vestibular system—independent of the drowsiness effects).

For adults in midlife and beyond, this translates into a higher fall risk. In a 2019 cohort of 10,698 older adults, higher anticholinergic burden from drugs such as diphenhydramine increased the hazard of a fall or fall-related injury, with certain combinations of moderate- and strong-potency anticholinergics having ~2x fall and fall-injury risk compared with lower-burden combinations.

Tolerance and dose escalation

With regular use, the body also develops tolerance to diphenhydramine’s effects. The initial dose that produced drowsiness becomes less effective over time, One pattern I’ve seen is some individuals will switch between diphenhydramine and doxylamine (Unisom SleepTabs and NyQuil) to “reset” the effect.

This pattern of tolerance and dose escalation matters because the risks scale with cumulative exposure, which brings us to the brain health consideration.

Section 2. Benadryl for sleep: Why Benadryl touches brain aging, not just drowsiness: the anticholinergic effect

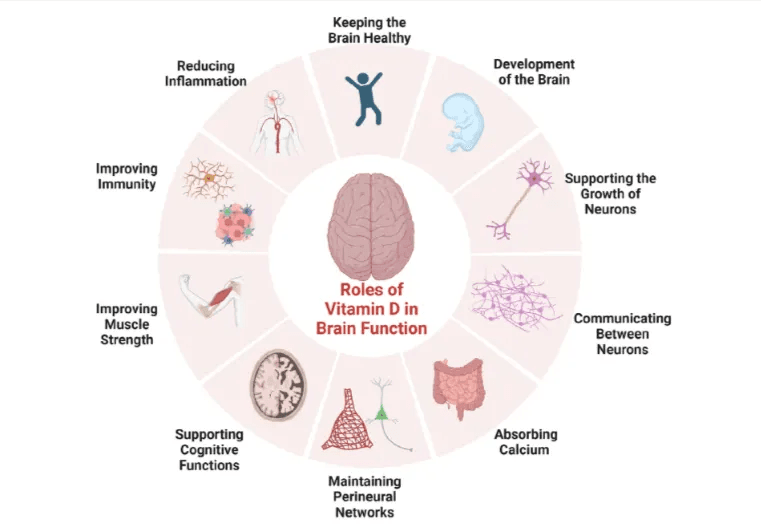

To understand why frequent use of over-the-counter older antihistamines raises concerns for long term brain health, we need to look at a different mechanism: anticholinergic activity.

What is acetylcholine, and what does it do?

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter with two main jobs.

- In the brain, it plays a central role in learning, memory formation, and attention.

- In the rest of the body, it stimulates muscle contractions and supports autonomic functions.

The body produces acetylcholine from choline, an essential nutrient found in eggs, liver, and other foods.

This is particularly relevant because acetylcholine production naturally declines with age, and the brain potentially becomes more sensitive to anything that further disrupts acetylcholine activity.

Anticholinergic drugs blunt acetylcholine’s action.

—by blocking acetylcholine from binding to its receptors.

Diphenhydramine and doxylamine both have anticholinergic activity, which is why it produces dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation—these are all effects of blocking acetylcholine in the body.

They sit in the same broad category as tricyclic antidepressants, bladder medications used for urgency or overactivity, and certain drugs used in Parkinson’s disease.

The concern is not an isolated dose during a bad allergy flare.

The concern is cumulative anticholinergic burden:

How much exposure you build up over years across all your medications and over-the-counter products.

Long-term associations with dementia.

A team from the University of Washington tracked ~3,500 adults ages >65 for ~7 years. The researchers documented all prescription and over-the-counter drugs each participant had taken in the 10 years before the study began.

During the follow-up period, ~800 participants developed dementia. When the researchers examined anticholinergic drug use, this is what they found:

- People using anticholinergic drugs had higher dementia incidence than those not using them.

- Taking an anticholinergic for the equivalent of ≥ 3 years was linked with ~54% higher dementia risk compared to taking the same dose for ≤ 3 months, even after accounting for other influences.

A 2023 analysis that focused on anticholinergic burden saw a similar pattern:

- Long-term use of 1 anticholinergic drug increased dementia incidence roughly 1.5–1.6-fold.

- Long-term use of 3+ anticholinergic drugs together increased dementia incidence to roughly 2.5–2.6-fold.

This does not mean, Benadryl alone causes dementia in any one individual.

It means that long-standing use of anticholinergic drugs—is an exposure your brain has to carry.

That exposure is something you can influence.

Section 3: Benadryl for sleep: Benadryl disrupts brain-protective-sleep architecture—even when it helps you stay asleep

Sleep cycles through distinct stages, with each stage serving different physiological functions. REM (rapid eye movement) sleep supports emotional processing, memory consolidation, and cognitive function.

Over time, chronic REM disruption may contribute to mood dysregulation, impaired memory, and reduced cognitive resilience.

A randomized trial in healthy men found those taking diphenhydramine:

- had a longer delay before their first REM period (REM latency ~138 minutes versus ~100 minutes without the drug)

- spent a smaller % of total sleep in REM (about 16.2% versus 20.5%).

This effect on REM is related to the anticholinergic mechanism discussed earlier. Acetylcholine is one of the neurotransmitters that promotes REM sleep. Blocking it with an anticholinergic drug suppresses REM.

This creates a situation where the drug produces unconsciousness but undermines the restorative properties of natural sleep.

Many people describe their antihistamine-assisted sleep as feeling drugged rather than truly rested. This makes sense given the mechanism. The drug suppresses wakefulness, but it also suppresses the natural sleep stages that produce the feeling of restoration.

In sum, when we zoom out, a Benadryl routine for sleep is doing three things at once:

- Slowing reflexes and decision-making into the next day.

- Adding to your anticholinergic burden over years.

- Reshaping your REM sleep in a way that does not support long-term cognitive health.

That is very different from taking a targeted step to correct the physiology that drives your 2–4 a.m. wakeups.

Section 4. How to think about your sleep problems in a way that matches the complexity of your physiology

Some people do need ongoing treatment where these medications play a role.

If that is you, and the drug is medically important, consider sitting down with your clinician and ask whether another option exists for your situation, and whether your overall anticholinergic load can be reduced by adjusting other medications.

The rest of this section focuses on people who are using older antihistamines primarily as a sleep solution.

Instead of “what can I take at night?” consider asking this: “What is my body doing, and how can I support it more intelligently?”

The wellness loop offers another sleep gummy, another gadget, or a longer list of evening habits. Those can help at the margins. They do not address the more important question:

What is my body doing to produce this repeated sleep pattern, and how can I support that process in a way that matches midlife and later-life physiology?

Your body is not running a one-line script. Hormones, circadian timing, breathing, pain and metabolic factors all interact during your sleep window.

A single-target approach—whether that’s diphenhydramine, melatonin, or any other compound—can move one part of the process while the underlying physiology that drives the disruption stays intact.

This is why someone can take a sedating antihistamine for three years and still need it every night: it doesn’t address what’s creating the symptom.

A more foundational strategy starts with seeing the pattern and then organizing your next steps around root causes.

Section 5: how to stop taking Benadryl for sleep safely: A step by step process toward identifying the root causes of your sleep problem

What follows is a framework for examining your own sleep pattern with more precision.

The goal is not to give you more tips (that may be marginally relevant to you) but to help you identify what your body is doing and focus your effort on the factors that matter most for your sleep recovery.

Step 1: Give Your Current Sleep Precise Descriptors

For the next 7–10 days, record when you fall asleep, when you first wake up, and how long you remain awake during those waking periods. At the end of the tracking period, write a one-line label that captures the pattern.

Examples:

- “5–6-hour ceiling with 3 a.m. wired wakeup”

- “Easy onset but 2–4 a.m. restless window”

- “Multiple 20-minute wakeups after 2 a.m.”

- “Wake up energized”

- “Wake up tired”, etc.

The point is to treat your sleep as having patterns. Patterns have causes.

Step 2. Connect that pattern to your daytime life

Next, make a short list of how this exact pattern shows up when you are awake: slower thinking, more word-finding trouble, feeling less steady, needing more effort for ordinary tasks, feeling less confident driving or making decisions.

This moves the conversation from “I wish I slept longer” to “this pattern is affecting my independence, my cognition, and my daily function.”

That reframe matters for motivation and for how you prioritize the work ahead.

Step 3. Sort your situation into root-cause buckets

Look at your pattern, your health history, and the last several years of your life, and ask which drivers sound most like you. Your sleep pattern is one set of clues. Your body and daytime function provide others—many of which run concurrent with sleep changes to inform on the patterns that help you identify the cause of your sleep issues. They can include:

Men:

- Reduced stress recovery, irritability, or feeling “wired but tired”—often linked to testosterone changes

- Difficulty maintaining or gaining muscle mass despite consistent training and adequate protein

- Longer recovery from workouts or reduced stamina

- Increased midsection fat despite no big change in diet or movement

- Lower drive, reduced confidence, or morning fatigue

- Nighttime urination, influenced by testosterone changes

- Hotter at night in the upper body with cooler hands and feet, sometimes tied to altered testosterone

Women:

- Heightened stress reactivity or anxiety that escalates more easily—often linked to progesterone or estrogen changes.

- Temperature dysregulation or night sweats.

- Nighttime urination from urethral or bladder tissue changes linked to estrogen changes.

- New joint stiffness or tendon aches on waking

- Increased frequency of UTIs or irritation

Both:

- Mood shifts, brain fog, or motivation changes that appeared alongside sleep disruption.

- Circadian disruption from screens and irregular schedules.

- Pain or physical discomfort.

- Snoring, reflux, coughing, or other breathing-related issues.

- Blood sugar swings or late heavy meals.

- Side effects from other medications that sedate or stimulate.

Most people can circle two or three that match their lived experience.

That is enough. You are moving from “I have bad sleep” to “I have a pattern driven by these specific factors.”

Step 4. Choose one main driver to work on over the next 4-6 weeks

From the factors you circled, pick the one that feels most central: hormone changes, circadian timing, breathing, pain, bladder, or metabolic factors. Commit to focusing on that area for the next four to six weeks.

That might mean an inflammation/pain-related project, a hormone-focused project, a circadian and light-timing project, or an assessment focused on breathing and oxygen during sleep.

This helps you move away from scattered tips and toward a targeted project that matches your pattern.

Step 5. Decide how you want to learn and implement a root-cause plan

Once you can see your main driver and your questions, you face a choice in how to move forward.

One path is to assemble things yourself, reading and synthesizing peer reviewed articles.

The other path is to follow an organized educational roadmap built around your age range, hormone stage, and sleep pattern, with an order of operations. That kind of roadmap is how you translate root-cause thinking into day-by-day changes while you gradually dial back use of sedating products.

The key move is recognizing that long-term sustainable sleep recovery is a learning and implementation project.

Step 6. Prepare for a different kind of medical visit

If you opt for a medical sleep evaluation and solution, you can bring this to your clinician.

Bring your sleep-pattern name, a rough timeline of when it started, the drivers you identified, your one-sentence hypothesis, and the questions you wrote down.

Then the conversation can center on: “Here is what my sleep is doing and what I think is driving it. How do we investigate and support that?”

That’s a different conversation from: “What else can I take at night?”

For most adults midlife and beyond, chronic sleep difficulty is a signal that something in the body’s regulatory processes—metabolic, hormones, circadian timing, breathing, or some combination—needs support.

OTC antihistamine (and other sedatives) mask that signal. The alternative is not finding a safer sedative.

It’s asking what your body is doing and building a strategy that respects the complexity of your physiology.

That’s a longer path.

It’s also the one that leads somewhere other than dependence on a drug that produce sedation at a cost.

It’s a path toward agency—independence not just from sedatives, but from the cycle of buying the next wellness product or waiting for the next appointment to tell you what to try.

That independence is what protects the life you’re building: the relationships, the hobbies, the energy to do the things you love.

Until next time,

—Kat

P.S. Write down three things you’d have more capacity for if you were living at 7–8 hours of sleep most days—hobbies, relationships, travel. That list matters more than your step counter.

If your pattern looks like 3 a.m. wakeups wrapped around slower recovery from workouts, harder time holding or building muscle, lower drive, feeling more revved up by stress, and more nighttime bathroom trips, you can look at the order of operations I use for that scenario here.

References

- Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R, Yu O, Crane PK, Larson EB. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Mar;175(3):401-7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. PMID: 25621434; PMCID: PMC4358759.

- Poonawalla IB, Xu Y, Gaddy R, James A, Ruble M, Burns S, Dixon SW, Suehs BT. Anticholinergic exposure and its association with dementia/Alzheimer’s disease and mortality in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023 Jun 30;23(1):401. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04095-7. PMID: 37391728; PMCID: PMC10311860.

- Green AR, Reifler LM, Bayliss EA, Weffald LA, Boyd CM. Drugs Contributing to Anticholinergic Burden and Risk of Fall or Fall-Related Injury among Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia and Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Drugs Aging. 2019 Mar;36(3):289-297. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-00630-z. PMID: 30652263; PMCID: PMC6386184.

- Weiler JM, Bloomfield JR, Woodworth GG, Grant AR, Layton TA, Brown TL, McKenzie DR, Baker TW, Watson GS. Effects of fexofenadine, diphenhydramine, and alcohol on driving performance. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in the Iowa driving simulator. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Mar 7;132(5):354-63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00004. PMID: 10691585.

- Katayose Y, Aritake S, Kitamura S, Enomoto M, Hida A, Takahashi K, Mishima K. Carryover effect on next-day sleepiness and psychomotor performance of nighttime administered antihistaminic drugs: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012 Jul;27(4):428-36. doi: 10.1002/hup.2244. PMID: 22806823.

- Culpepper L, Wingertzahn MA. Over-the-Counter Agents for the Treatment of Occasional Disturbed Sleep or Transient Insomnia: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015 Dec 31;17(6):10.4088/PCC.15r01798. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15r01798. PMID: 27057416; PMCID: PMC4805417.

- Clark JH, Meltzer EO, Naclerio RM. Diphenhydramine: It is time to say a final goodbye. World Allergy Organ J. 2025 Jan 25;18(2):101027. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2025.101027. PMID: 39925982; PMCID: PMC11803843.