If you’ve passed a kidney stone, you already know the pain.

What you may not know: ongoing oxalate exposure doesn’t just raise your risk of another stone—it may be damaging kidney tissue and accelerating kidney aging between episodes.

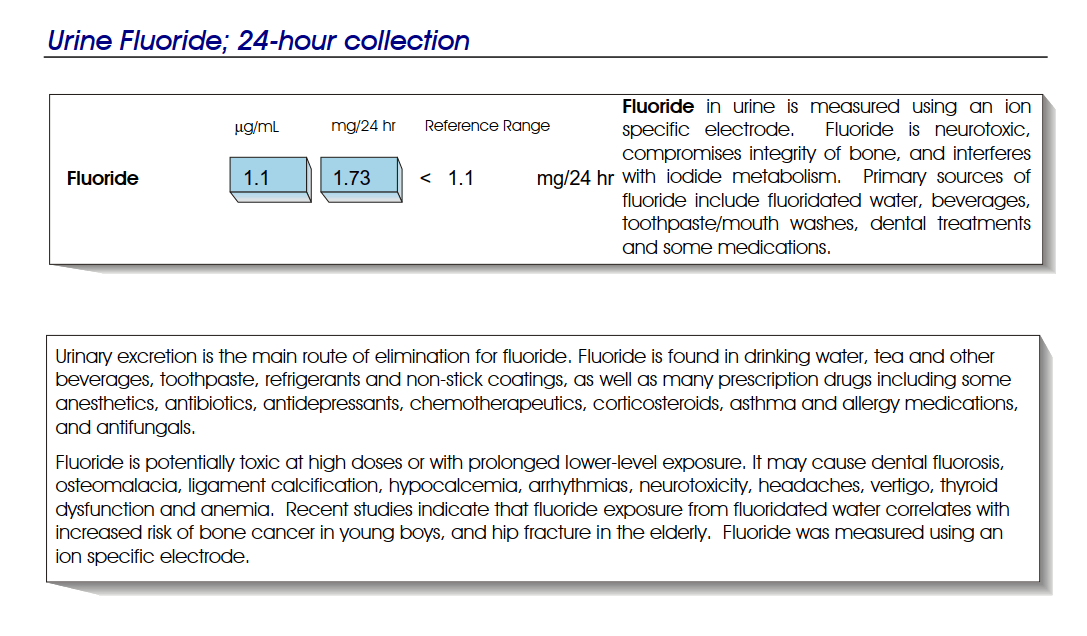

If you’ve never had a stone but you recently saw “elevated urinary oxalate” on a lab panel, the question is whether that number matters for long-term kidney function—even without symptoms.

And if you simply want to protect kidney health proactively—or eat a plant-forward diet—oxalate management may be relevant even if you’ve never tested.

This discussion is therefore vital for you if:

- You’ve had kidney stones and want to prevent another painful episode—and limit the kidney micro-damage happening between episodes.

- You haven’t had stones but want to reduce oxalate-related kidney stress before it becomes a kidney stone—or before it accelerates kidney aging.

Do Oxalates Matter If You’ve Never Had Kidney Stones—or If You’ve Already Had Them?

Oxalates (oxalic acid and its salts) are natural compounds found in many healthy plant foods (e.g. spinach, nuts, beets, etc.).

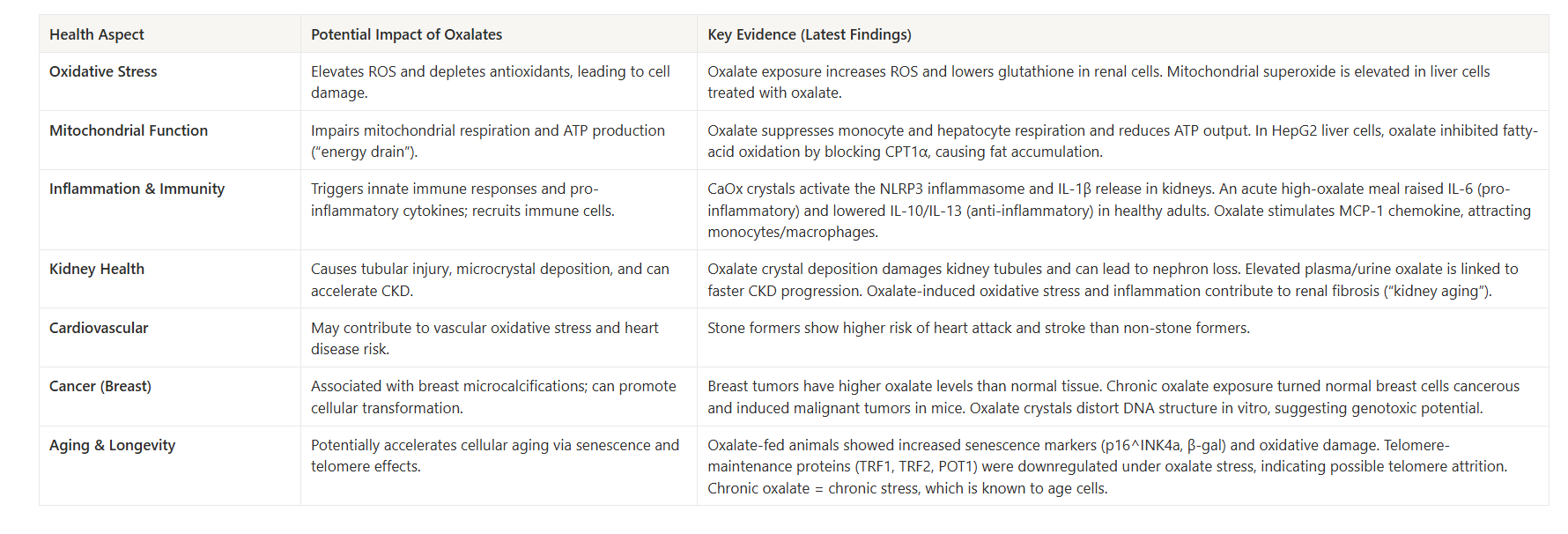

In the body, oxalate is a metabolic end-product that must be excreted, primarily by the kidneys. High levels of oxalate are known to form calcium oxalate kidney stones, but research now indicates that oxalates have other negative health effects even in people without kidney stones.

Below, we explore potential impacts on kidney function, longevity, mitochondria, and chronic disease risk.

Section 1. Oxalates and Kidney Health (Beyond Kidney Stones)

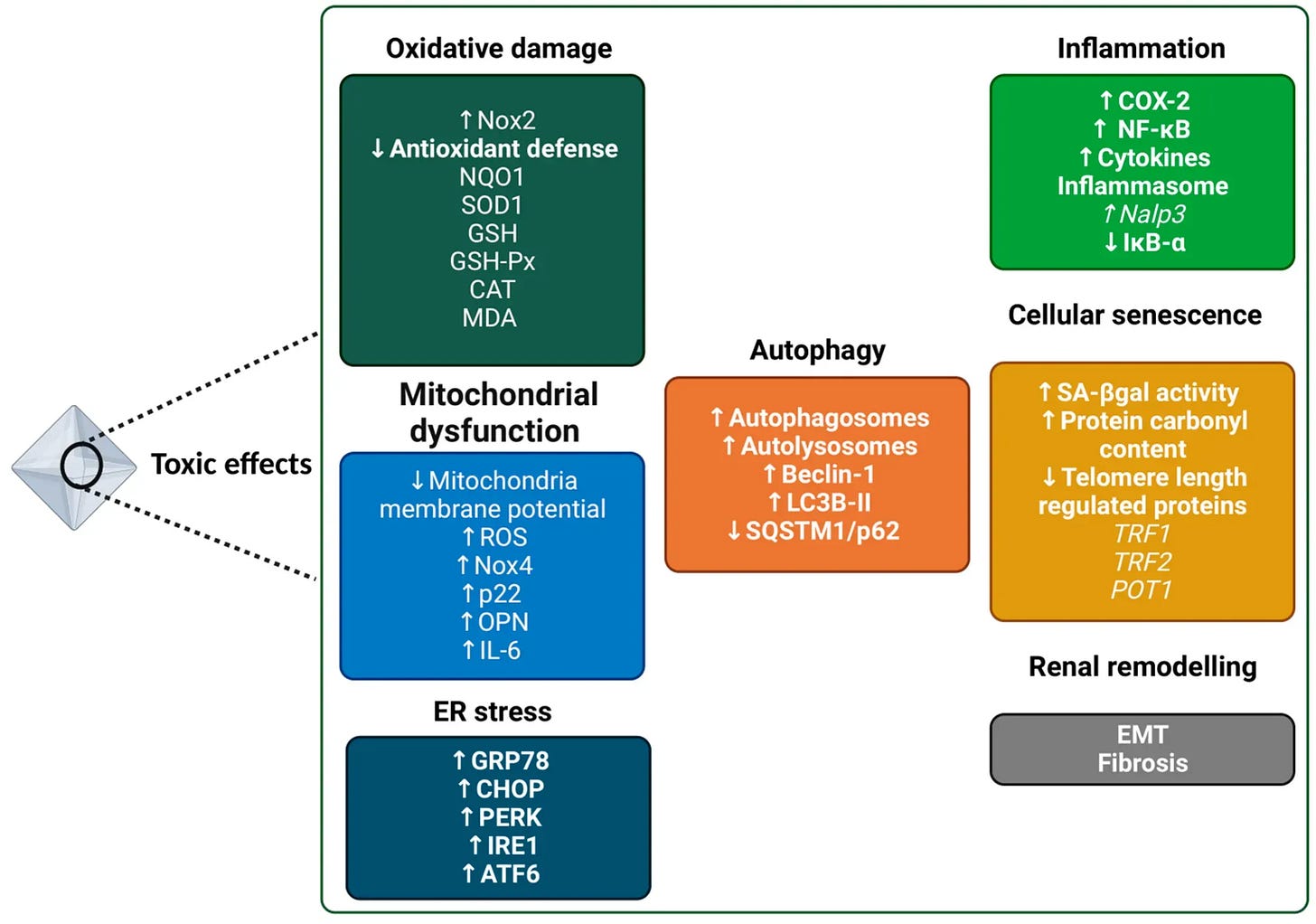

Even without visible kidney stones, oxalate affect the kidneys over time. The kidneys are the main excretory route for oxalate, and they are highly susceptible to oxalate’s effects. Microscopic calcium oxalate crystals can form in renal tubules and provoke local inflammation and injury. Studies show that calcium oxalate (CaOx) crystals induce oxidative stress in kidney tubular cells, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell damage. These tiny crystal deposits can incite an inflammatory response (via the NLRP3 inflammasome and IL-1β release) that causes tissue irritation and scarring in the kidney. Over years, repeated oxalate micro-injury may contribute to a decline in kidney function or accelerated “kidney aging.”

In other words, oxalate is not just a stone risk – it can also be a nephrotoxin at sustained levels, potentially causing subtle kidney damage even in those without a history of stones.

Subclinical Kidney Damage and “Silent” Kidney Aging

Emerging 2024 data indicate that oxalate-rich diets may gradually degrade kidney health over time, even in people without kidney stones or prior kidney disease.

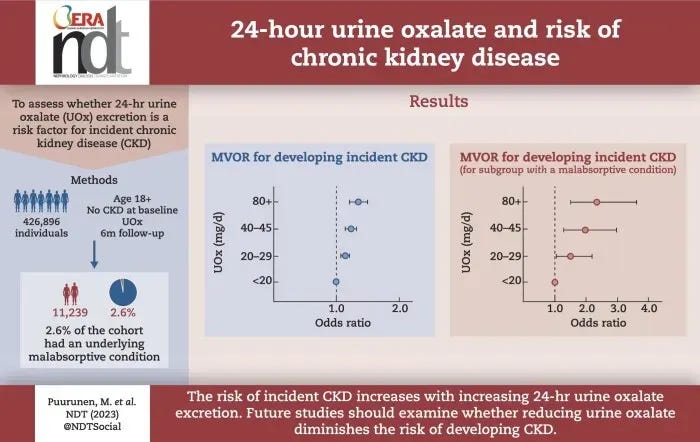

A large longitudinal study (Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024) followed over 426,000 generally healthy adults and found a clear dose-response relationship between:

- urinary oxalate excretion vs.

- risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Participants with only moderately elevated 24-hour urinary oxalate (e.g. in the 20–30 mg/day range) had higher odds of incident CKD over ~3 years compared to those with <20 mg/day. The risk kept rising across higher oxalate categories, and this held true after adjusting for factors like diet, comorbidities, urine volume, etc.

Such epidemiological evidence suggests that habitual oxalate load may contribute to subclinical kidney injury and functional decline (“kidney aging”) even when no kidney stones form.

Systemic Inflammation & Chronic Disease Links

Beyond the kidneys and cells, oxalate may act as a driver of systemic inflammation. When oxalate crystals deposit or oxalate levels remain high, the immune system can mount a sterile inflammatory response (since crystals are seen as foreign). Research in animal models has shown that oxalate crystal exposure activates immune pathways like the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β) and recruitment of immune cells to affected tissues. Oxalate in circulation can also affect circulating monocytes and macrophages, as noted, shifting them toward a more inflammatory state (lower IL-10, higher oxidative activity).

This chronic low-grade inflammation might not cause immediate symptoms but could contribute to long-term health issues. Elevated oxalate levels have been associated with several chronic diseases in epidemiological studies. For example, researchers have noted links between oxalate and atherosclerosis and hypertension. One hypothesis is that oxalate-induced oxidative stress can damage blood vessel lining or promote vascular inflammation, thereby accelerating arterial plaque formation (atherosclerosis) or impairing endothelial function (raising blood pressure).

Oxalate’s association with metabolic diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes has also been observed – possibly because these conditions alter oxalate metabolism or because oxalate-induced inflammation worsens metabolic health. Notably, kidney stone formers (who typically have higher oxalate exposure) tend to have higher rates of cardiovascular events and metabolic syndrome in some studies.

Taken together, mechanistic data (inflammation, oxidative stress) and the epidemiologic associations above provide a link between chronic oxalate exposure and diseases of aging.

Oxalates, Longevity, and “Aging” Markers

Given oxalate’s propensity to cause oxidative stress and inflammation, it could also impact longevity or biological aging markers.

Chronic oxidative stress is a well-known accelerator of aging processes (damaging DNA, proteins, and mitochondria), and chronic inflammation (“inflammaging”) is likewise linked to age-related decline. If a oxalates impose even a mild oxidative/inflammatory burden, over decades this might incrementally contribute to tissue aging. One concern is the long-term load on the kidneys – our kidneys naturally lose function very slowly with age, but higher oxalate might speed this up.

Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction caused by oxalate can impair cell energy and promote cellular senescence or apoptosis, which are hallmarks of aging.

Even at subclinical levels, a health-conscious person may want to avoid unnecessary oxalate excess to reduce avoidable pro-aging stress on the body.

Mitochondria & Oxidative Stress

Another reason oxalate is harmful is its effect on cellular metabolism and mitochondria.

Mitochondria are the energy powerhouses of cells, and they are sensitive to oxidative stress. Oxalate exposure has been shown to disrupt normal mitochondrial function in various cell types. For instance, a study in healthy adults found that a high oxalates not only led to transient nanocrystals in urine, but also reduced monocyte cellular bioenergetics – essentially lowering the energy output of these immune cells. Follow-up laboratory research revealed that oxalate can directly cause mitochondrial dysfunction: monocytes and macrophages treated with oxalate showed increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, a drop in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, and impaired mitochondrial and lysosomal function.

Oxalate also hampered autophagy (the cell’s waste clearance process) in these immune cells. In kidney epithelial cells, calcium oxalate crystals similarly trigger overproduction of ROS and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, which damages the mitochondria and can initiate cell death.

In short, oxalate creates oxidative stress inside cells and disrupts mitochondrial health.

Over time, chronic oxidative stress and mitochondrial injury are known to contribute to aging and organ dysfunction.

This expands our understanding of oxalate’s impact beyond crystal formation, highlighting intracellular damage pathways. It further reinforces that subclinical oxalate crystal exposure can set off pathogenic cascades in otherwise healthy cells.

For a health-conscious individual, the key point is that oxalates can strain cellular defenses, adding to the cumulative oxidative stress burden that contributes to aging and disease, within and beyond the kidneys.

Health aspects influenced by oxalates beyond kidney stone formation.

Section 2. Oxalate Load Isn’t Only About Spinach & Plant Foods

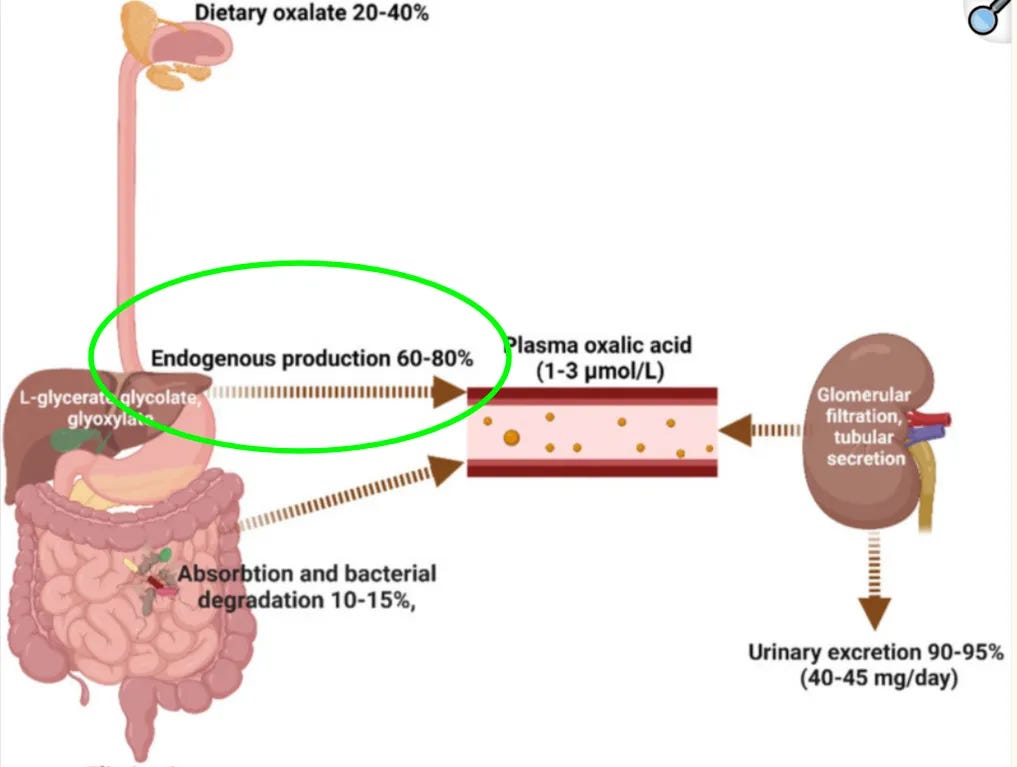

📌 In humans, most urinary oxalate is produced inside the body rather than coming directly from food.

In typical mixed diets with normal kidney function,

- ~20–50% of urinary oxalate is dietary,

- which means roughly 50–80% is produced inside the body by the liver (”endogenously”).

On a very low-oxalate or near-zero-oxalate diet, 100% of urinary oxalate is, by definition, coming from internal production.

That also means a strategy built only around “eat less spinach, skip the beet juice, cut back on almonds and dark chocolate”—even if perfectly implemented—at best addresses only a small fraction of your total oxalate load.

That internal oxalate production is driven by normal metabolism running through glyoxylate-related pathways. These pathways are influenced by the liver-oxalate axis, metabolic inputs (unrelated to eating oxalate-containing foods) and how we manage other aspects of health, which means they can be evaluated and adjusted—but not by oxalate food lists alone.

Oxalate is also widely distributed across plant foods—hundreds of vegetables, grains, nuts, seeds, herbs, and fruits contain some amount—so completely “avoiding oxalate” would require an impractically narrow diet. Whether you are trying to prevent your first kidney stone or reduce the chances of a second or third episode while protecting long-term kidney function, the realistic goal is not to delete oxalate foods from your life.

The goal is to manage oxalate load more intelligently.

This requires, for example strategies for:

- limiting how much oxalate is absorbed into the bloodstream so the kidneys do not have to clear as much, and

- addressing internal liver production in a structured way.

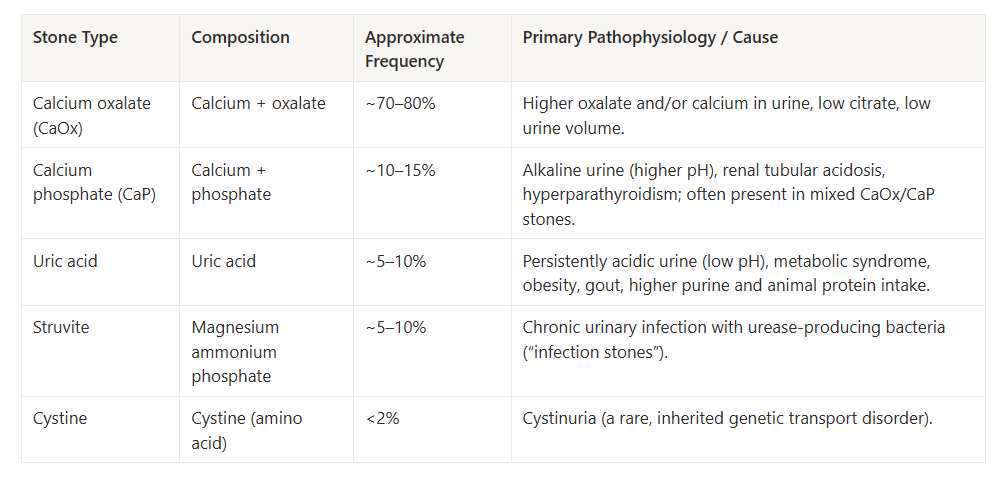

How Much Of The Kidney Stone Problem Is Driven By Oxalate

Most kidney stones are calcium-based, and calcium oxalate stones dominate that group.

For most adults with a history of stones, this means calcium oxalate is either the primary stone type or a major component. Oxalate management is therefore not a niche concern—it is directly connected to the most common stone phenotype.

Section 3. What This Means If You’ve Had Kidney Stones—or Want to Prevent Them

Taken together, the 2022–2025 data show that oxalate is more than a passive crystal that sometimes forms kidney stones.

At higher or sustained levels, it behaves as a repeat stressor for kidney tissue and mitochondria, and higher urinary oxalate is linked to faster chronic kidney disease progression and higher CKD risk, even when no stones are present.

Even outside the kidney stone world, this sits against a backdrop of rapidly rising kidney disease.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) now affects ~790 million adults globally (~10% of the adult population), up from ~380 million in 1990. In the United States alone, an ~35.5 million adults (≈14%) have CKD, and > 800,000 live with end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis or transplant.

Oxalate is not the only driver of CKD or dialysis, but avoidable oxalate burden is one of the levers we can act on early—before kidneys are pushed toward that end of the spectrum and before kidney decline undercuts blood pressure control, metabolic resilience & longevity.

- If you have already had kidney stones, oxalate management is not only about avoiding another acute, painful episode. It is also about reducing ongoing crystal deposition, local inflammation, and oxidative stress that can erode kidney function and accelerate kidney aging over time.

- If you have never had stones, this is about reducing oxalate-related kidney stress before it becomes a kidney stone—and before it accelerates kidney aging.

📌 Most guidance stops at a short list: drink more water, eat less salt, avoid a handful of “high-oxalate foods,” maybe boil your vegetables and dump the water, and hope that is enough.

In practical terms,

- you cannot remove oxalate completely: your body produces it continuously, and

- many otherwise beneficial plant foods contain it.

Intelligent oxalate management for kidney stone prevention requires, for example:

- preventing as much oxalate absorption into your bloodstream as possible, so your kidneys have less to process, and

- in addressing the internal pathways that can drive overproduction when certain systems are out of balance.

The effective strategy, therefore, is a structured process to understand and manage your specific oxalate pattern:

- Clarify which aspects of your history, daily pattern, and existing data place you at higher oxalate risk.

- Use a focused oxalate audit and management framework to address the factors most likely to influence kidney stone risk and kidney aging in your case.

- Assess whether your body’s internal oxalate overproduction is likely to be part of the picture and, if so, follow a targeted risk-reduction approach.

- For those who want data, learn which kidney stone–relevant tests (beyond urinary oxalate tests and kidney function panels) can meaningfully inform an oxalate strategy—and when testing is optional vs. strategically helpful.

My Kidney Stone Prevention & Risk Reduction System: The Vault Oxalate Audit & Risk Management Compass walks you through that process step by step.

Reduce your kidney stone risk and protect long-term kidney function—starting today.

Warmly,

—Kat

P.S. The Kidney Stone Prevention & Risk Reduction System, is accessed through a private link to the Portal (shown below), you receive after purchase, so you’re getting a structured digital system—not a static PDF.

It is built on an evidence base of 110+ peer-reviewed studies (1990–2025). Preview of the system dashboard:

Select References

- Full Oxalate & Kidney Stone References Library (1990-2025)

- Castellaro AM, Tonda A, Cejas HH, Ferreyra H, Caputto BL, Pucci OA, Gil GA. Oxalate induces breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015 Oct 22;15:761.

- Chaiyarit S, Thongboonkerd V. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Kidney Stone Disease. Front Physiol. 2020 Oct 20;11:566506.

- Waikar SS, Srivastava A, Palsson R, Shafi T, Hsu CY, Sharma K, Lash JP, Chen J, He J, Lieske J, Xie D, Zhang X, Feldman HI, Curhan GC; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort study investigators. Association of Urinary Oxalate Excretion With the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1;179(4):542-551.

- Baltazar, P.; de Melo Junior, A.F.; Fonseca, N.M.; Lança, M.B.; Faria, A.; Sequeira, C.O.; Teixeira-Santos, L.; Monteiro, E.C.; Campos Pinheiro, L.; Calado, J.; et al. Oxalate (dys)Metabolism: Person-to-Person Variability, Kidney and Cardiometabolic Toxicity. Genes 2023, 14, 1719.

- Hawkins-van der Cingel G, Walsh SB, Eckardt KU, Knauf F. Oxalate Metabolism: From Kidney Stones to Cardiovascular Disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2024 Jul;99(7):1149-1161.

- Liu J, Liu X, Guo L, Liu X, Gao Q, Wang E, Dong Z. PPARγ agonist alleviates calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis by regulating mitochondrial dynamics in renal tubular epithelial cell. PLoS One. 2024 Sep 26;19(9):e0310947.

- Puurunen M, Kurtz C, Wheeler A, Mulder K, Wood K, Swenson A, Curhan G. Twenty-four-hour urine oxalate and risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024 Apr 26;39(5):788-794.

- Wu L, Xue X, He C, Lai Y, Tong L. Cell death‑related molecules and targets in the progression of urolithiasis (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2024 Jun;53(6):52.

- Kumar P, Patel M, Oster RA, Yarlagadda V, Ambrosetti A, Assimos DG, Mitchell T. Dietary Oxalate Loading Impacts Monocyte Metabolism and Inflammatory Signaling in Humans. Front Immunol. 2021 Feb 25;12:617508.

- Kumar P, Laurence E, Crossman DK, Assimos DG, Murphy MP, Mitchell T. Oxalate disrupts monocyte and macrophage cellular function via Interleukin-10 and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling. Redox Biol. 2023 Nov;67:102919.

- Nishizawa, Y., Miyata, S., Tosaka, M. et al. Serum oxalate concentration is associated with coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular events in Japanese dialysis patients. Sci Rep 13, 18558 (2023).

- Zeng, Z., Xu, S., Wang, F. et al. HAO1-mediated oxalate metabolism promotes lung pre-metastatic niche formation by inducing neutrophil extracellular traps. Oncogene 41, 3719–3731 (2022).

- Prochaska ML, Moe OW, Asplin JR, Coe FL, Worcester EM. Evidence for abnormal linkage between urine oxalate and citrate excretion in human kidney stone formers. Physiol Rep. 2021 Jul;9(13):e14943. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14943. PMID: 34231328; PMCID: PMC9814525.

- Trbojevic-Stankovic, J. (2022, November). Oxalate handling in health and disease—Crosstalk gut and kidney. NEP Newsletter.

- Mitchell T, Kumar P, Reddy T, Wood KD, Knight J, Assimos DG, Holmes RP. Dietary oxalate and kidney stone formation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019 Mar 1;316(3):F409-F413.

- Stepanova N. Oxalate Homeostasis in Non-Stone-Forming Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review of Key Findings and Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2023 Jun 7;11(6):1654. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11061654. PMID: 37371749; PMCID: PMC10296321.

- Bargagli M, Tio MC, Waikar SS, Ferraro PM. Dietary Oxalate Intake and Kidney Outcomes. Nutrients. 2020 Sep 2;12(9):2673.

- Chen T, Qian B, Zou J, Luo P, Zou J, Li W, Chen Q, Zheng L. Oxalate as a potent promoter of kidney stone formation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Jun 5;10:1159616. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1159616. PMID: 37342493; PMCID: PMC10278359.

- Febriana L. et al. A review on the pharmacotherapy and case studies of hypercalciuria and hyperoxaluria. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, 2022.

- Xu Y, You J, Yao J, Hou B, Wang W, Hao Z. Klotho alleviates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction through the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, thereby reducing renal senescence induced by calcium oxalate crystals. Urolithiasis. 2025 Mar 29;53(1):61.

- GBD 2023 Chronic Kidney Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease in adults, 1990–2023, and its attributable risk factors: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. The Lancet 406(10518), 2461–2482 (2025).

- Deng, L., Duan, L., He, C., Zhao, T., Pan, W., Xu, Y., Pan, H., Qin, S. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease and its underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health 25, 927 (2025).

- Bikbov, B., Purcell, C.A., Levey, A.S. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733 (2020).

- Reducing the burden of noncommunicable diseases through promotion of kidney health and strengthening prevention and control of kidney disease https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB156/B156_CONF6-en.pdf

- GBD 2023 Kidney Failure with Replacement Therapy Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of kidney failure with replacement therapy and associated aetiologies, 1990-2023: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet Glob Health. 2025 Aug;13(8):e1378-e1395.

- Francis, A., Harhay, M.N., Ong, A.C.M. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol 20, 473–485 (2024).

- See E, Ethier I, Cho Y, Htay H, Arruebo S, Caskey FJ, Damster S, Donner JA, Jha V, Levin A, Nangaku M, Saad S, Tonelli M, Ye F, Okpechi IG, Bello AK, Johnson DW. Dialysis Outcomes Across Countries and Regions: A Global Perspective From the International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas Study. Kidney Int Rep. 2024 May 23;9(8):2410-2419.

- Junejo, S.; Chen, M.; Ali, M.U.; Ratnam, S.; Malhotra, D.; Gong, R. Evolution of Chronic Kidney Disease in Different Regions of the World. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4144.

- Burrows NR, Koyama A, Pavkov ME. Reported Cases of End-Stage Kidney Disease — United States, 2000–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:412–415. DOI:

- US Renal Data System 2024 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States Johansen, Kirsten L. et al. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Volume 85, Issue 6, A8 – A11