Does Short Sleep Impair Blood Sugar Control (Even with a Healthy Diet?)

We’ve all felt it — the day after a short or restless sleep when sugary treats feel more tempting and energy dips too soon.

That response isn’t just from fatigue. Instead, it reflects changes in blood sugar regulation.

According to the Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2023 update from the American Heart Association, more than 1/3 adults sleeps < 7 hours per night—an everyday pattern linked to metabolic changes, independent of diet or activity levels.

In mid-life and later adulthood, when glucose tolerance naturally declines, the impact of insufficient sleep becomes more pronounced.

Still, “poor sleep” isn’t one problem with one cause.

Some individuals don’t get enough hours; others fall asleep easily but wake repeatedly; still others sleep at a schedule that misaligned with their circadian rhythm.

Each of these patterns points to a different underlying driver — and all of these impact blood sugar control.

This article examines the first of these patterns: chronic short sleep—habitually sleeping less than the body requires. We will look at what recent large-scale studies (2023–2025) reveal about its effect on blood-sugar regulation in 3 groups:

- Healthy adults

- Adults with prediabetes

- Healthy adults at elevated cardiometabolic risk (elevated BMI, family history)

After reviewing the evidence, we will conclude with 10 practical strategies to help you extend total sleep time.

Let’s get started.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

Section 1. Does Chronic Short Sleep Impair Blood Sugar Control in Healthy Individuals?

Chronic insufficient sleep – habitually getting less sleep than needed – is a significant risk factor for impaired blood sugar control and type 2 diabetes.

Recent large-scale studies confirm earlier findings that people who consistently sleep too little are more likely to develop metabolic issues.

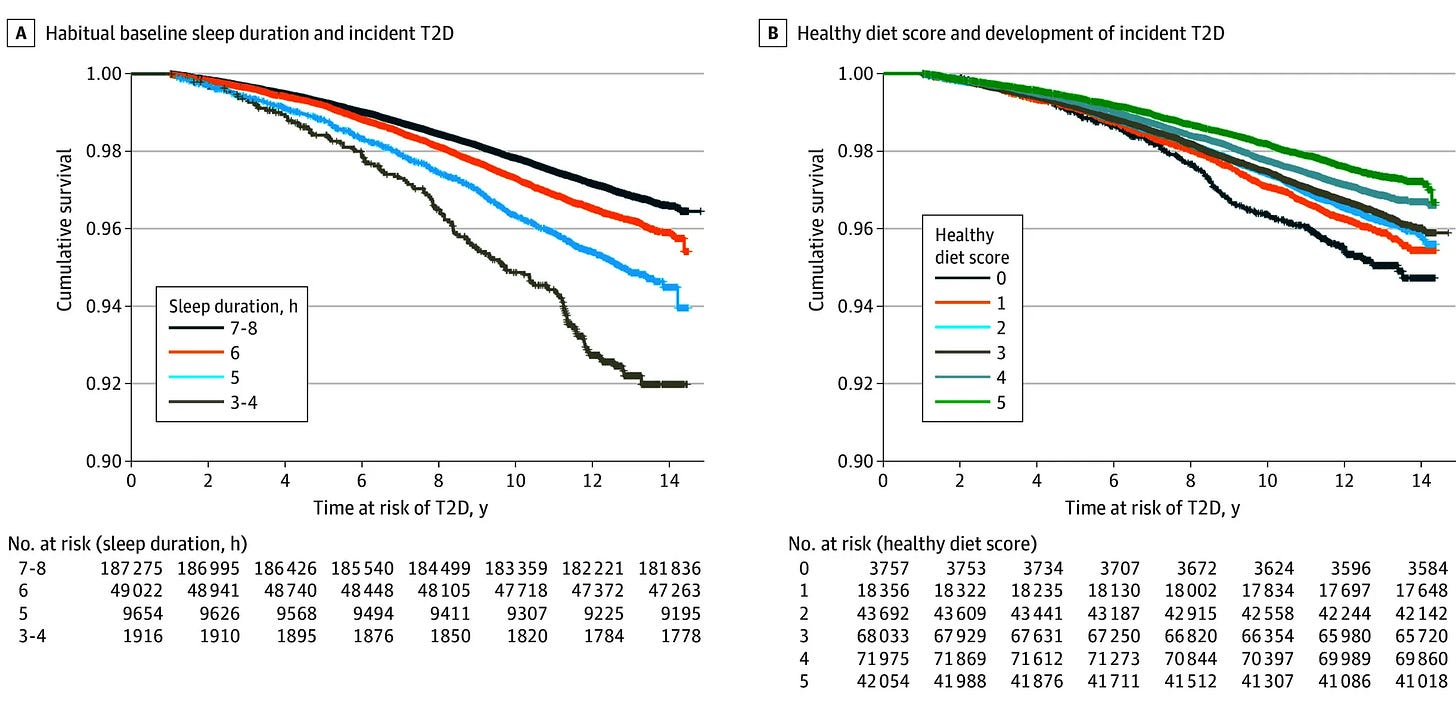

For example, a 2024 analysis of 247,000 middle-aged adults in the UK found that those sleeping <6 hours per night had a markedly higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes over ~12 years, compared to those sleeping 7–8 hours.

Specifically:

- Sleeping ≈ 5 hours per night → 16 % higher risk (adjusted HR 1.16 [95 % CI 1.05–1.28])

- Sleeping 3–4 hours per night → 41% higher risk (adjusted HR 1.41 [95 % CI 1.19–1.68])

What makes this study notable is that the analysis statistically accounted for an extensive range of variables to isolate the effect of sleep duration:

- Demographic & Social Factors: (including age, biological sex, socioeconomic status measured by the Townsend index, and educational level).

- Race and Ethnicity: (self-reported categories including African or Caribbean, Asian, White European, or other combined groups, which were tracked because some groups have higher reported rates of T2D).

- Key Lifestyle Habits: (including a healthy diet score, smoking status, frequency of alcohol intake, and physical activity level).

- Baseline Clinical Metrics: (including Body Mass Index and systolic blood pressure).

- Co-existing Health Factors: (including the frequency of insomnia symptoms and the use of antidepressants, both of which can independently influence sleep and metabolism).

Even after these adjustments, short sleep duration remained independently associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Specifically, this increased diabetes risk with short sleep persisted even in participants who maintained a healthy diet and lifestyle.

Mechanistic studies mirror this pattern.

When sleep drops below physiologic need, muscle and liver cells become less responsive to insulin. This causes the pancreas to secrete more of it to maintain normal blood sugar levels. Over time, this compensatory pattern creates a state of low-grade insulin resistance—one that can progress even in lean, otherwise healthy adults.

If this is the effect in healthy individuals, what happens in those already more susceptible?

That’s where we turn next—chronic short sleep in prediabetic adults.

Section 2. Does Chronic Short Sleep Impair Blood Sugar Control in Prediabetics?

Evidence from a Systematic Review (~122 000 adults with prediabetes)

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis including approximately 122 000 adults aged 40–60 years concluded that chronic short sleep accelerates the transition from prediabetes to diabetes.

- Individuals sleeping <6 hours per night had a 60% higher risk of progressing from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes compared with those sleeping 7–8 hours (adjusted hazard ratio 1.6 [95 % CI 1.1–2.6])

Evidence from a Large Cohort (81 233 adults with prediabetes)

In a separate 2018 cohort study of 81 233 adults with prediabetes:

- Insomnia was associated with a 28–32% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes during follow-up, even after adjustment for baseline glucose measures and lifestyle factors.

The authors concluded that disturbed sleep—through shortened duration, fragmented continuity, or insomnia—appears to accelerate metabolic deterioration by increasing insulin resistance and impairing β-cell recovery.

Together, these studies indicate that chronic short or fragmented sleep does not merely correlate with higher blood sugar—it accelerates progression from prediabetes to diabetes.

Sleep duration therefore stands as a 3rd modifiable pillar of diabetes prevention, alongside nutrition and physical activity.

So what happens when these same sleep patterns occur in individuals who appear metabolically healthy but are genetically or physiologically predisposed to insulin resistance?

That’s where we turn next.

Section 3. Does Chronic Short Sleep Impair Blood Sugar Control in Healthy but Susceptible Population?

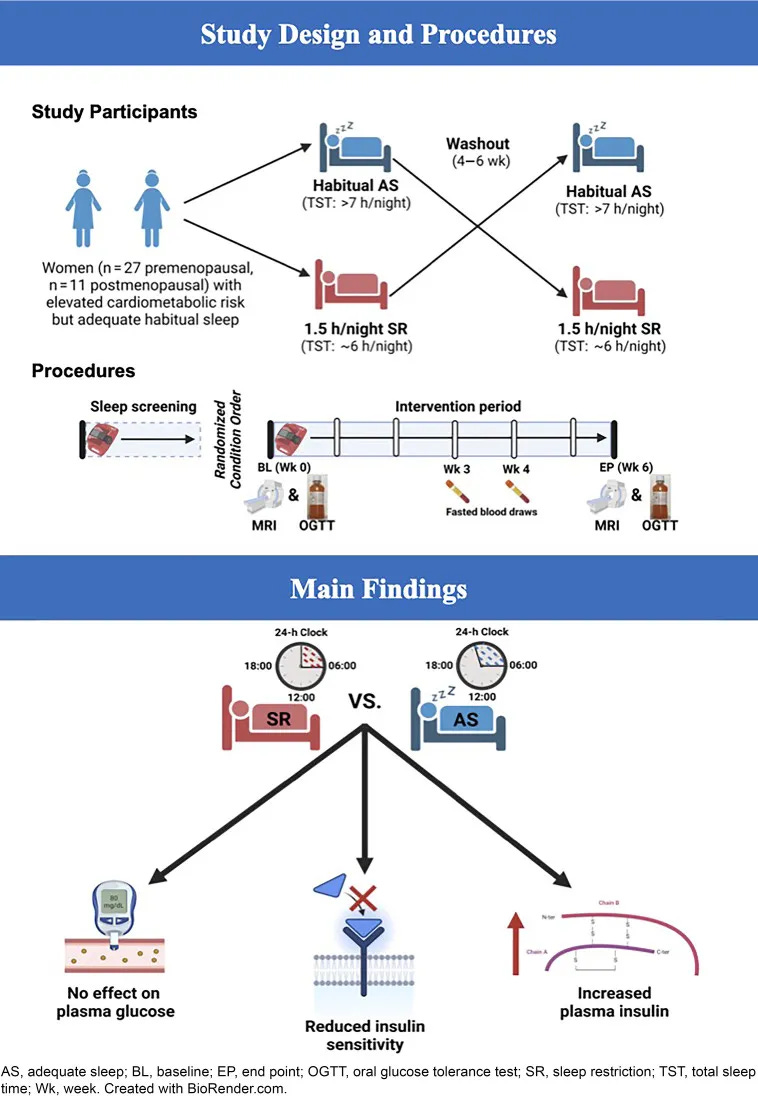

In a randomized crossover trial—a study design where each participant experiences both conditions (adequate sleep and restricted sleep) in alternating phases—researchers modestly reduced nightly sleep to mimic real-world sleep loss.

The study involved generally healthy individuals who did not have diabetes or prediabetes but were considered at elevated cardiometabolic risk due to either overweight or a family history of type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease.

Participants reduced sleep from roughly 7.5 hours to 6.2 hours per night for 6 weeks.

Here are the results:

- Fasting insulin increased significantly with sleep restriction (SR),

- HOMA-IR (insulin resistance index) increased — especially in postmenopausal women, where the rise was nearly 2x that of premenopausal women.

- Glucose levels (fasting and post-meal) did not significantly change, which is typical in early insulin resistance: the body compensates with higher insulin

Importantly, these impairments occurred without significant weight gain, confirming that the effect stemmed directly from sleep loss rather than increases in body fat.

Taken together, the findings indicate that routinely getting too little sleep—even a chronic deficit of just ~1-2 hours per night—can meaningfully worsen insulin sensitivity over time.

Indeed, epidemiological data link chronic short sleep to higher fasting blood sugar levels and higher HbA1c (a long-term blood sugar marker) in various populations.

In sum, prolonged sleep deficiency pushes the body toward a pre-diabetic state by inducing insulin resistance—an early shift that, if unaddressed, raises long-term risk for type 2 diabetes and related cardiometabolic disorders.

However, because sleep duration is both measurable and modifiable, these findings highlight an advantage: unlike genetics or age, this risk factor is actionable and can be improved.

The next section turns to practical strategies—10 tactics that specifically help you extend total sleep time.

Section 4. What You Can Do—10 Strategies That Extend Sleep Duration

The evidence we’ve reviewed, while extensive, points to a powerful and optimistic opportunity. Unlike many risk factors, sleep duration is modifiable.

The American Heart Association now includes it as one of “Life’s Essential 8” health metrics, on par with diet and exercise.

But how?

The strategies that follow focus on external barriers—the structural, scheduling, and behavioral factors that shorten sleep duration.

They’re not designed to rebuild internal sleep capacity—the physiological ability to fall asleep & stay asleep (that I discuss in the Vault 5-Part Sleep Clarity Series) which often involves deeper work of hormonal support, circadian timing, and autonomic regulation.

Instead, the tools below are some practical quick wins aimed at helping you get an extra 20-40 minutes of sleep by addressing everyday friction points that limit total sleep time and can be very effective if your body can sleep soundly, but structural barriers are preventing you from getting the 7-9 hours you need.

So, without further ado….

Here Are 10 Strategies That Help You Sleep Longer Tonight

1. Schedule sufficient time in bed—and work backward from there

If you need 8 hours of actual sleep, you likely need ~9 hours in bed to account for time falling asleep and brief awakenings. If your alarm is set for 6:30 AM, that means lights out by 9:30-10 PM—which means wrapping up evening tasks, meals, and screens earlier than most might plan for.

2. Eliminate early-morning light intrusion

Blackout curtains/eye mask prevent dawn light from triggering premature cortisol rise and early waking—especially important for those who naturally wake at 4-5 AM

3. Recognize when naps are compensating for insufficient night sleep

If you regularly nap, you may not be sleeping enough at night—eliminate naps for 2 weeks and observe if nighttime duration naturally extends

4. Allow natural wake-up to assess true sleep need. Most people underestimate their actual sleep requirement. Use weekends or a vacation (ideally at least 7–10 alarm-free days) to discover your body’s natural baseline. If you’ve been undersleeping for months or years, expect your body to initially extend to 9-10 hours as it compensates for accumulated sleep debt. After that initial period, your duration will likely settle into your true physiologic need, whether that is 7, 8, or 9 hours.

5. Address early-morning noise disruption

White noise machine or earplugs block sounds (partner movement, pets, traffic, neighbors) that cause premature waking in light sleep phases, when you could have slept until 7 AM but were woken at 6.

6. Track sleep debt vs. sleep need separately

If you “need” 8 hours but have been getting 6.5, you are accumulating a sleep debt—temporary 9-hour nights are compensation, not necessarily an indicator that 9 hours is your new, permanent requirement.

7. Decouple exercise timing from a fixed morning schedule.

While a 5 AM workout is a common habit, if it consistently cuts sleep short, consider shifting it. Moving exercise to a lunch break or early evening can add 60–90 minutes of sleep without losing the training stimulus.

8. Move pets out of bedroom

Pet movement, noise, and space competition reduce total sleep time by 15-40 minutes per night on average

9. Delay morning commitments by 30-60 minutes

If consistently cutting sleep short to meet 6 AM obligations, shifting schedule to 6:30 or 7 AM adds duration without lifestyle overhaul

10. Use gradual alarm retreat protocol

If you’re locked into an early wake time, shifting your alarm abruptly by 60-90 minutes is often ineffective. Our internal circadian rhythm is calibrated to the existing schedule and can typically only shift by about 15-30 minutes per day. An abrupt, large change triggers resistance.

Instead, push your alarm back 15 minutes every week or every few days until you reach your target duration. This gradual retreat allows both your routine and your circadian rhythm to recalibrate. (Week 1: 6:15 AM. Week 2: 6:30 AM. Week 3: 6:45 AM.)

Warmly,

—Kat

P.S. If your sleep has changed since midlife—lighter, shorter, or more fragile under stress—habits alone are not enough. The midlife hormonal transition often shifts how your body regulates sleep, but that function can be supported at any age.

The Sleep OS: Hormones was designed for this stage. It offers a self-paced, step-by-step process to strengthen hormonal pathways that stabilize sleep—without hormone therapy or lab testing.

👉 You can learn more about my most popular program, the Trio Hormone Framework, here:

👉 Or, explore the foundational Sleep & Stress Single Hormone Frameworks here:

References

- Mostafa SA, Mena SC, Antza C, Balanos G, Nirantharakumar K, Tahrani AA. Sleep behaviours and associated habits and the progression of pre-diabetes to type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2022 May-Jun;19(3):14791641221088824.

- LeBlanc ES, Smith NX, Nichols GA, Allison MJ, Clarke GN. Insomnia is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the clinical setting. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018 Dec 26;6(1):e000604.

- Joseph Henson, Alix Covenant, Andrew P. Hall, Louisa Herring, Alex V. Rowlands, Thomas Yates, Melanie J. Davies; Waking Up to the Importance of Sleep in Type 2 Diabetes Management: A Narrative Review. Diabetes Care 23 February 2024; 47 (3): 331–343.

- Zuraikat FM, Laferrère B, Cheng B, Scaccia SE, Cui Z, Aggarwal B, Jelic S, St-Onge MP. Chronic Insufficient Sleep in Women Impairs Insulin Sensitivity Independent of Adiposity Changes: Results of a Randomized Trial. Diabetes Care. 2024 Jan 1;47(1):117-125.

- Nôga DA, Meth EMES, Pacheco AP, Tan X, Cedernaes J, van Egmond LT, Xue P, Benedict C. Habitual Short Sleep Duration, Diet, and Development of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Mar 4;7(3):e241147.

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147:e93–e621