REM Sleep: Yale Study Reveals How It Protects The Brain

REM sleep—the phase marked by vivid dreaming and rapid eye movements—plays a distinct role in preserving brain structure that extends beyond next-day cognitive performance.

New longitudinal research suggests that REM architecture may specifically protect brain regions most vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease. When REM quality deteriorates, three changes may unfold:

- Accelerated brain volume loss in default mode network regions

- Structural decline in areas that show early Alzheimer’s vulnerability

- Bidirectional cycles where brain atrophy further degrades REM quality

Most sleep tracking estimates REM duration and percentages, but the evidence points to REM quality—the depth, consolidation, and true architecture of these phases—as the key factors in long-term brain protection.

Why REM Quality Matters for Brain Longevity

➤ Our brain’s structural integrity depends on sleep architecture—not just sleep duration.

While we often focus on getting 7-8 hours, emerging research suggests that how our brain cycles through sleep stages may determine which regions remain resilient as we age. REM sleep facilitates emotional memory integration, synaptic pruning, and network recalibration in ways that other sleep phases cannot replicate.

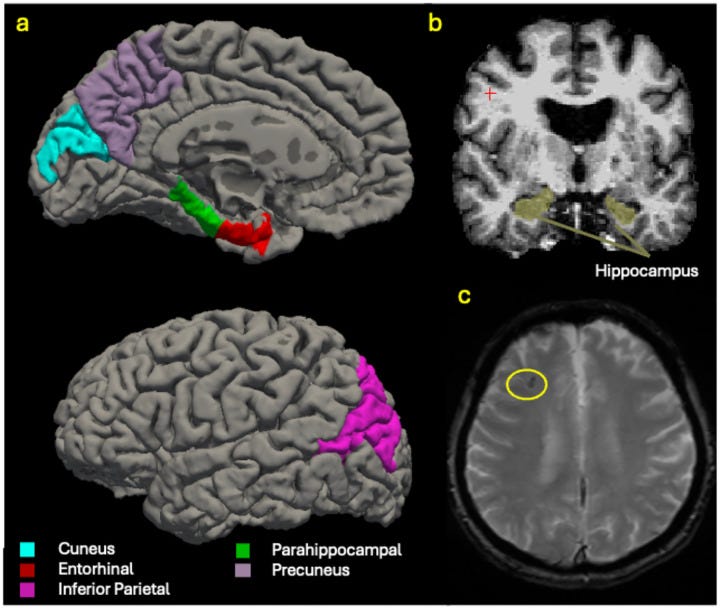

The stakes seem higher for brain regions that show early vulnerability in Alzheimer’s disease. These areas—including the inferior parietal lobule, precuneus, and default mode network hubs—rely on quality REM architecture to maintain their structural integrity over decades.

Sleep deficiency is associated with the atrophy of the inferior parietal region, which is observed in early AD. Sleep architecture may be a modifiable risk factor for AD. – Gawson Cho, Yale School of Medicine

Losing REM quality doesn’t just affect tomorrow’s cognitive performance. It may initiate structural changes that compound over years, accelerating brain volume loss in regions essential for memory, attention, and self-referential thinking.

Most concerning: by the time we notice cognitive changes, structural atrophy may already be underway. Understanding REM’s protective role offers a window into early intervention—while our brain architecture is still modifiable.

By the way, If you’ve been following my work on hormones and sleep, you’ll know how much depth there is beneath the surface.

If you’re ready to go deeper and take a systems-based approach to improving your sleep, Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.

or

Your First Action Step: Personalize Your Sleep Improvement Journey

Everyone’s sleep is unique. Some struggle to fall asleep, others wake too early, and each pattern points to a different solution.

This short personalization path helps you pinpoint which pattern applies to you, focus where improvement matters most, and receive resources that fit your sleep profile:

Personalize Your Sleep Improvement Journey

It’s the starting point for tailoring future insights to how you improve your sleep.

So What’s the Evidence That REM Protects These Brain Regions?

A 2025 study from Yale School of Medicine provides some of the most recent data.

Researchers followed 270 community-dwelling adults over 13–17 years, combining gold-standard polysomnography with high-resolution MRI scans to track how sleep architecture influences brain structure over time.

The methodology was fairly rigorous: Participants underwent full overnight polysomnography—not consumer sleep tracking—measuring REM proportions, slow-wave sleep percentages, and arousal indices.

Brain imaging occurred 13–17 years later, targeting six regions known to show early Alzheimer’s-related atrophy.

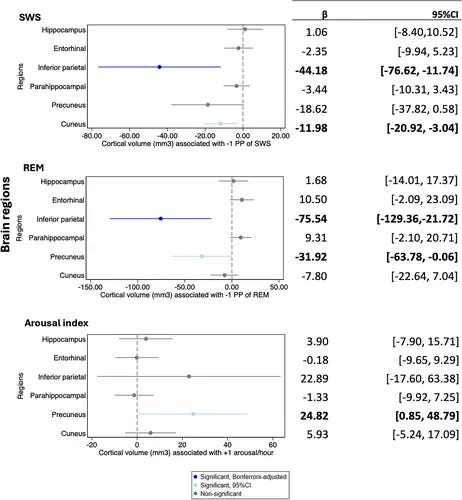

The findings were region-specific and dose-dependent:

- Lower REM sleep was associated with smaller volumes in the inferior parietal lobule (β = −75.54 mm³ per 1 percentage point decrease) and precuneus (β = −31.92 mm³ per 1 percentage point decrease)

- These associations remained statistically significant even after adjusting for age, sex, education, APOE4 genotype, total sleep time, sleep apnea severity, baseline cognitive function, and cardiovascular risk factors

- Slow-wave sleep showed complementary effects but with different regional specificity—affecting the cuneus and inferior parietal regions

What makes this study compelling is what it controlled for.

The researchers accounted for intracranial volume, APOE4 status (the strongest genetic Alzheimer’s risk factor), baseline cognitive performance, and comprehensive medical histories. The REM-brain volume relationship persisted despite these adjustments.

Interestingly, sleep architecture showed no association with cerebral microbleeds—small vessel damage often linked to cognitive decline. This suggests REM’s protective effects operate through distinct mechanisms beyond vascular pathways.

What’s Happening in Your Brain When REM Sleep Drops?

The Yale findings point to 3 mechanisms that explain why REM deficiency may accelerate brain aging:

- REM proportion versus absolute duration matters more than total sleep time. The study measured REM as a percentage of total sleep, not just minutes. You could sleep eight hours but still have compromised brain protection if REM represents a small proportion of that time. Fragmented or shallow REM—even within adequate total sleep—may leave brain networks susceptible to structural decline.

- The relationship appears bidirectional. Poor REM architecture may drive brain atrophy in regions that regulate sleep, which further degrades REM quality. Once this cycle begins, each component reinforces the other. Early intervention on sleep architecture may prevent this cascade, but reversing it potentially becomes more challenging as structural changes accumulate.

- Network-specific vulnerability reveals why certain brain regions are affected first. REM loss doesn’t affect all areas equally. The inferior parietal lobule and precuneus are central hubs in the default mode network—a system active during rest, introspection, and memory consolidation. These regions process self-referential information and integrate memories with personal meaning. When REM quality degrades, these high-demand areas may experience disproportionate metabolic stress, making them more susceptible to volume loss.

- This explains why early Alzheimer’s changes emerge in default mode network regions before affecting the hippocampus or more obvious memory centers.

Therefore, the brain areas most dependent on quality REM architecture may be the first to show structural vulnerability.

How Can You Know if Your REM Quality Is Protecting Your Brain? Here’s What I Track:

The Yale study used research-grade polysomnography, but there are observable signs of quality REM architecture that don’t require lab equipment:

- Vivid dream recall patterns that occur naturally upon waking, without trying to remember. Quality REM typically produces coherent, emotionally meaningful dreams that feel different from fragmented sleep imagery.

- Morning cognitive clarity versus grogginess. REM consolidates emotional and procedural memories overnight. When this process works efficiently, you wake with mental sharpness rather than cognitive fog.

- Mood stability upon waking. REM helps regulate emotional reactivity and stress responses. Consistent quality REM often correlates with more stable mood and emotional resilience throughout the day.

- Sleep efficiency patterns that reflect consolidated, not just sufficient, sleep. Many wearables can track sleep efficiency, but the timing and duration of deep phases matter more than total percentages.

I experienced sleep difficulties for 15 years, including 2 years of sleep tracking when I did not have consistent subjective REM quality markers (the ones I listed above). Despite testing various sleep protocols during that tracking period, my mornings remained cognitively sluggish and vivid dream recall was infrequent.

Since I addressed my underlying sleep issues, I now fairly consistently wake with dream memories & mental clarity.

Here’s the interesting comparison: throughout both periods, my Oura ring reported similar sleep efficiency, sleep scores and REM percentages. During the 2 years when subjective REM markers were absent, the device still registered what appeared to be satisfactory sleep quality.

This points to a gap between what consumer trackers measure and the real-world quality of our sleep architecture—the architecture that protects brain regions.

Algorithmic estimates may miss the qualitative differences—depth, consolidation, proper stage transitions—that determine whether REM sleep provides neuroprotective benefits.

In essence, if standard sleep metrics look adequate but we lack the subjective REM quality markers, the architecture protecting our brain long-term may differ from what devices suggest.

P.S. Many individuals optimize for sleep metrics their device shows them. But it’s the quality and consolidation of these phases that has the greatest influence on long-term brain health.

Sleep OS: Hormones targets the hormonal systems that shape sleep depth and continuity—aspects of sleep architecture that often become affected during midlife. As these endocrine patterns shift, sleep often becomes lighter or more fragmented. However, hormonal decline isn’t inevitable and hormone function can be strengthened at any age with targeted support.

If stress has become more difficult to manage or sleep less restorative since midlife, it can be a sign that these hormonal systems can benefit from support. That’s what this digital program was built to address—you can see if Sleep OS Hormones is right for you here.

Sleep OS Hormones is now available as a 60-day self-guided program with dedicated systems for estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, or bundled together for a more complete approach.