Tylenol: A Longevity Perspective for 50+, Is Tylenol Bad For Your Liver?

Because acetaminophen appears in so many products—from cold remedies to pain relievers and sleep aids—it’s easy to overlook how the total amount can approach the maximum daily dose without any single moment feeling notable.

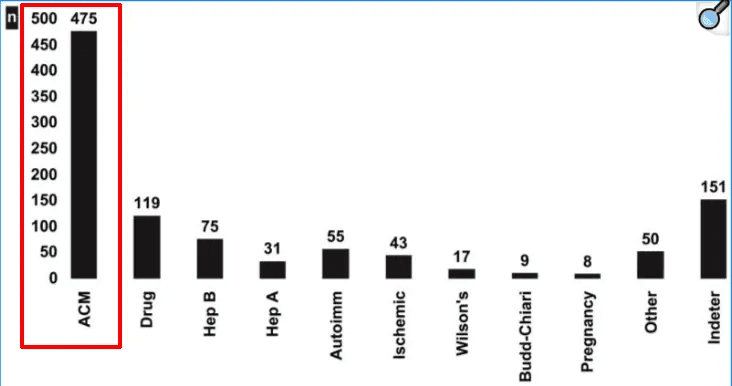

For context (& autism-related discussions aside)—acetaminophen accounts for roughly 46–50% of acute liver-failure cases in the United States, often from unintentional overuse when individuals combine over-the-counter products that share the same active ingredient.

Even within recommended limits, however, certain situations can reduce liver clearance capacity and narrow the safety margin of Tylenol—and of any other medication.

This article therefore examines everyday acetaminophen use through a longevity lens for adults 50+.

To understand why context matters, it helps to begin with how the liver clears acetaminophen—and where that bottleneck can occur.

Most of each acetaminophen dose is processed by the liver and excreted.

A small portion, however, is converted into a short-lived toxic compound called N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). The liver typically neutralizes this compound by attaching it to glutathione, an antioxidant it synthesizes and eliminates it through bile and urine.

Whether that neutralization proceeds smoothly depends on glutathione availability.

And, as we will discuss, those reserves can drop in both age-independent or age-related scenarios that affect liver function.

For longevity-focused adults, this process illustrates a broader principle: the liver’s detoxification capacity is finite, it varies depending on lifestyle factors and can decline gradually with age.

The sections that follow examine:

- why liver capacity matters for healthy aging,

- how acetaminophen fits into the larger picture of hepatic workload, and

- 4 actionable strategies to reduce acetaminophen need or to support the body’s natural clearance systems when they’re needed.

By the way, some of you have mentioned you haven’t been able to locate specific resources for some of the questions you have. I’ve gathered the main paths below so you can find what fits your situation.

So—what would help you most this month?

(Choose the one that feels most relevant right now — it’ll show you where to start.)

- Melatonin seems to be my main issue—help me understand why it isn’t working for me → Show me how

- Help me figure out whether age-related hormone changes are at the root of my sleep problems → Show me how

- I already know testosterone or estrogen are involved, but I don’t know how to restore balance or stability → Show me how

- My sleep seems more linked to stress or over-activation than to age-related sex hormone or melatonin changes. → Show me how

- None of these fit — I need / want help identifying what’s really causing my disrupted sleep → Show me how

- Sleep isn’t my focus right now — I’m working on broader longevity goals (glucose, gut, cardiovascular, etc.) → Show me how

Section 1 — Why Routine Tylenol Use Belongs in a Longevity Lens

When we look at the liver through a longevity lens, its role extends far beyond handling medications.

The liver performs more than 500 metabolic functions. It processes nutrients, synthesizes proteins, produces bile, stores glycogen, regulates hormones—all core systems that define vitality in later life.

And, central to this discussion—it detoxifies both endogenous and exogenous compounds:

- Endogenous compounds include hormones your body produces: estrogen, testosterone, cortisol, thyroid hormones. These are metabolized and cleared through the liver.

- Exogenous compounds include what we consume or absorb from the environment: medications, supplements, alcohol, environmental toxins, food additives, pesticide residues.

Much of the compounds the body encounters passes through overlapping enzymatic machinery

With age, this machinery changes.

Some phase I enzyme activity decline. Mitochondrial function in hepatocytes—the liver’s primary cells—often decreases.

Glutathione production also often declines, both from reduced synthesis capacity and from higher background demand.

For us optimizing for longevity, this matters because the liver is already managing a baseline load even before we add medications.

That load includes:

- Our own hormones

- Supplements we take—fat-soluble vitamins, herbal compounds, amino acids, metabolic cofactors

- Environmental exposures from food, water, air, personal care products, and household chemicals

- Prescription medications for blood pressure, cholesterol, thyroid function, etc.

Each compound that enters this system can compete for overlapping enzyme pathways and draws from the same cofactor pools—including glutathione.

When we add acetaminophen to this mix, we’re not adding it to a blank slate. We’re adding it to a system that’s already operating at a certain capacity level, and that capacity may be tighter than it was 20 years ago.

This framing shift—from “acetaminophen is safe” to “acetaminophen uses hepatic resources I want to preserve”—is what makes routine use worth examining through a longevity lens.

Section 2 — How the Liver Clears Tylenol—and When Detox Capacity Tightens

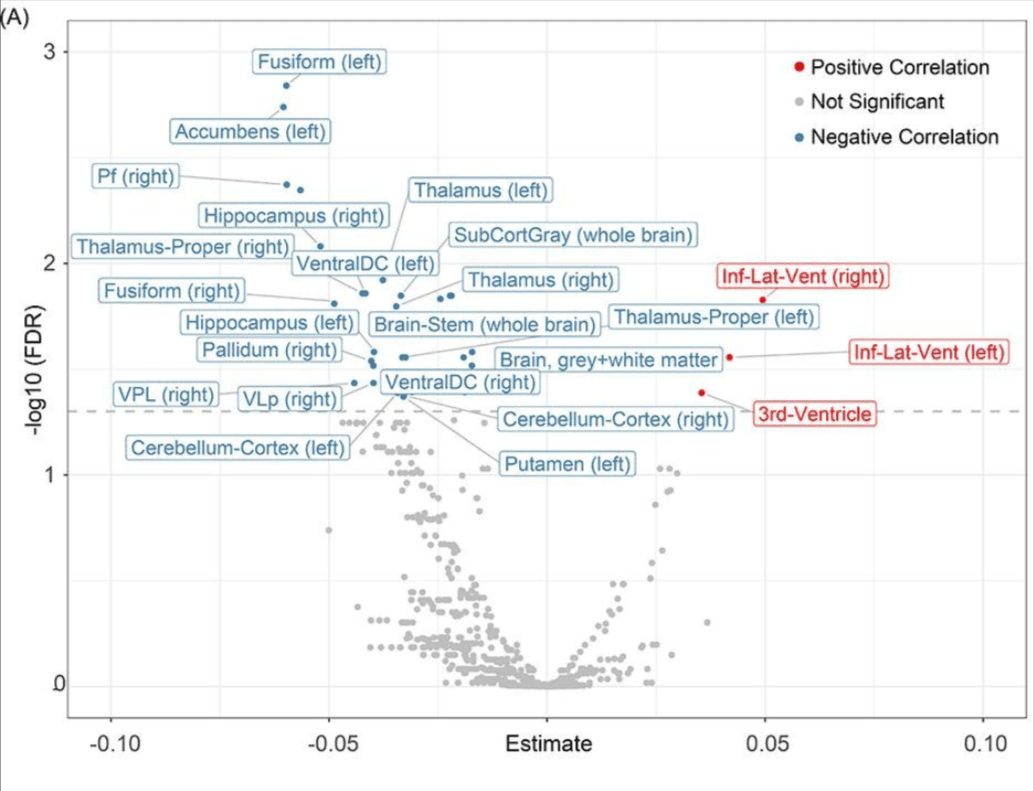

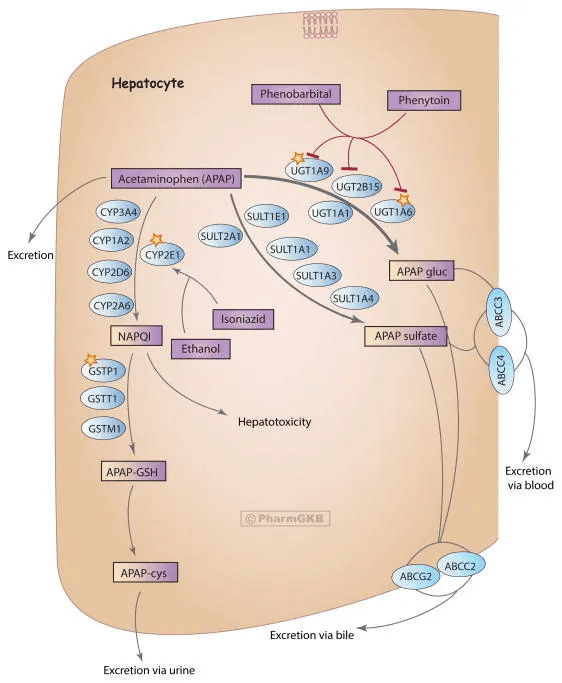

Acetaminophen mainly follows a one-pass hepatic clearance mechanism.

The majority of each dose undergoes glucuronidation or sulfation—conjugation reactions that attach water-soluble molecules to the drug, making it easy to excrete.

A smaller fraction is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, primarily CYP2E1, with contributions from CYP1A2 and CYP3A4.

This alternative pathway produces NAPQI, the reactive toxic intermediate I mentioned earlier.

Under normal conditions, glutathione (GSH) neutralizes NAPQI.

The process works efficiently as long as glutathione reserves are adequate and the rate of NAPQI formation stays within clearance capacity.

Problems potentially emerge when glutathione stores are insufficient to handle the NAPQI being produced.

So what are some scenarios that narrow the glutathione buffer?

- Reduced glutathione production: Fasting, very low-calorie intake, or insufficient dietary protein can lower the precursor supply needed for glutathione synthesis. Poor nutrient or chronic illness can have the same effect.

- Lower hepatic reserve in aging. Older adults can have diminished mitochondrial density and potentially reduced synthesis of the amino acid precursors cysteine and glycine. Both are required for glutathione production. Aging can also decrease enzyme efficiency and blood flow.

- Lower hepatic reserve independent of aging: Fatty liver, even mild cases, reduces functional liver mass. Polypharmacy increases use of the same detox pathways.

- Hormone and supplement load. Oral estrogen, progesterone, and some fat-soluble supplements use the same first-pass hepatic pathways. When taken concurrently, they can draw on overlapping conjugation systems.

- CYP enzyme induction: Certain medications and chronic alcohol use induce CYP2E1. Induction can increase the fraction of acetaminophen converted to NAPQI, especially with high dosing or shortly after alcohol clears.

The Broader Implication for Longevity

This mechanism highlights why even standard doses benefit from context considerations.

The question is not whether acetaminophen is safe in isolation—but whether the body’s antioxidant and conjugation systems are adequately supported at the moment of use.

Viewed through the longevity framework, the goal is to preserve hepatic buffering capacity rather than merely avoid acute injury.

The next section translates these insights into 4 concrete strategies—to help adults 50 + maintain that biochemical margin and reduce the need for frequent analgesic use.

Section 3 — Here are 4 Action Items to Preserve Hepatic Resilience & Reduce Analgesic Reliance for Longevity-Focused Adults

1. Preserve Glutathione on Fasting and Low-Calorie Days

Fasting or very low-calorie intake reduces the availability of cysteine and glycine, the rate-limiting amino acids for glutathione synthesis. During fasting, hepatic glutathione can drop as the liver uses existing stores without replenishing them at the usual rate. Additionally, glutathione recycling depends on NADPH and prolonged under-nutrition could lower this capacity. The net effect is a smaller buffer to neutralize NAPQI if acetaminophen is taken during this window.

What to consider: If you practice time-restricted eating or periodic fasting, avoid dosing acetaminophen on fasting days when possible. If pain relief is necessary, use conservative doses and avoid stacking multiple products. On low-calorie days, prioritize adequate protein intake to maintain amino acid availability.

This doesn’t mean fasting is incompatible with occasional acetaminophen use—just that the timing and total dose can benefit from more attention in this context.

2. Improve Sleep Quality to Lower Pain Sensitivity

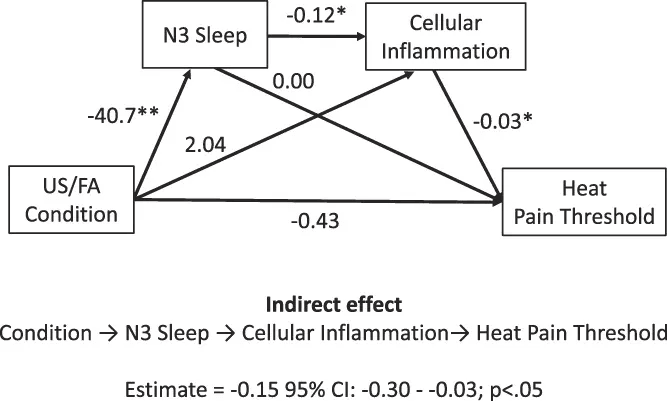

Modest sleep disruption increases pain sensitivity.

Studies show that sleep loss blunts the effectiveness of analgesics, which can drive more frequent dosing or higher doses to achieve the same relief. Chronic poor sleep also increases low-grade inflammation, which amplifies pain signaling. The result is a feedback loop: discomfort disrupts sleep, poor sleep heightens discomfort.

What to consider: Prioritize consistent sleep timing and uninterrupted sleep continuity. If musculoskeletal pain, headaches, or joint stiffness are recurring, investigate whether sleep quality is contributing. Addressing the root cause—whether it’s sleep apnea or hormone driven sleep issues—can reduce analgesic use more effectively than increasing medication.

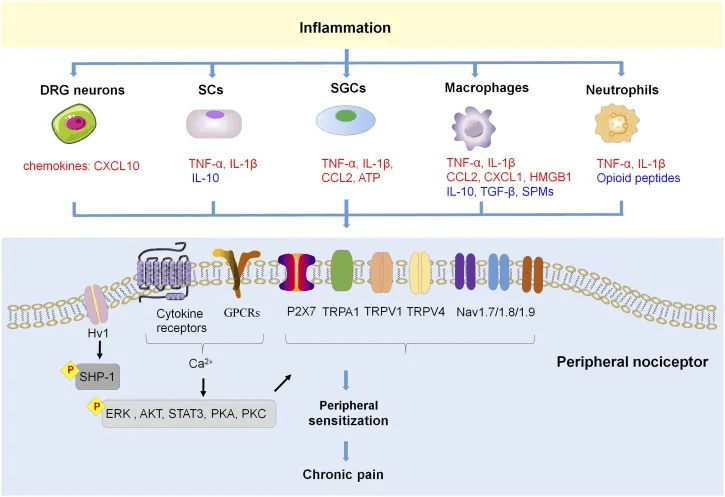

3. Lower Baseline Inflammation to Reduce Analgesic Demand

Persistent low-grade inflammation raises oxidative burden throughout the body, including the liver. It also increases perceived pain and discomfort.

What to consider: Keep baseline inflammation low through nutrition and environmental practices you likely are already mindful of polyphenol-rich foods, regular movement and minimizing exposure to pro-inflammatory triggers.

If you find yourself taking acetaminophen several times per week, consider whether inflammation is the underlying driver. Addressing root causes eliminate or reduce the need for symptomatic relief.

4. Monitor Liver Function If Use Is Frequent

Occasional acetaminophen use is unlikely to affect liver markers in most individuals.

If acetaminophen use is frequent—or if you’re managing multiple medications, oral hormones, or frequent supplements—consider checking liver function a few times a year.

What to consider: Basic liver function tests include:

- ALT (alanine aminotransferase): Enzyme released when liver cells are injured.

- AST (aspartate aminotransferase): Another enzyme released during liver damage. The AST/ALT ratio can help distinguish between different types of liver stress.

- Bilirubin: Measures the liver’s ability to process and excrete bile. Elevated bilirubin can indicate impaired liver function.

- Albumin: Protein synthesized by the liver. Low albumin may reflect chronic liver dysfunction.

- GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase): Enzyme that can indicate bile duct issues or alcohol-related liver damage.

These markers don’t tell you directly about glutathione status or NAPQI formation, but they provide a general picture of hepatic health.

If markers are elevated, it may be worth reassessing acetaminophen use, evaluating other hepatotoxic exposures (alcohol, medications, supplements), and working with a clinician to identify contributing factors.

Conclusion — Rethinking Liver Workload as a Longevity Practice

Acetaminophen isn’t high-risk for many—but it does draw on hepatic capacity that may already be stretched by certain lifestyle context or age.

This same logic applies to other compounds the liver processes.

The four practices outlined above—preserving glutathione on fasting days, stabilizing sleep, lowering inflammatory load, and checking liver markers when use is frequent—aren’t acetaminophen-specific.

They’re ways to reduce how often analgesics become necessary in the first place, and to support clearance capacity when they are used.

If you’re managing medications, hormones, or supplements, it may be worth reviewing your stack through this lens.

The liver processes what you give it—but when avoiding unnecessary demand is an option, that’s worth factoring in.

And, if you’re taking acetaminophen routinely, a question you may like to consider isn’t only “Is this safe.” Rather, “What else can I address so I don’t need this as often.”

Upgrade for personalized roadmaps—systematic implementation frameworks you can personalize to your specific biomarkers and risk factors.

References

- Fontana RJ. Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am. 2008 Jul;92(4):761-94, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.03.005. PMID: 18570942; PMCID: PMC2504411.

- Rubin JB, Hameed B, Gottfried M, Lee WM, Sarkar M; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Acetaminophen-induced Acute Liver Failure Is More Common and More Severe in Women. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jun;16(6):936-946. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.042. Epub 2017 Dec 2. PMID: 29199145; PMCID: PMC5962381.

- Mazaleuskaya LL, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, FitzGerald GA, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB summary: pathways of acetaminophen metabolism at the therapeutic versus toxic doses. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015 Aug;25(8):416-26. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000150. PMID: 26049587; PMCID: PMC4498995.

- Susa ST, Hussain A, Preuss CV. Drug Metabolism. [Updated 2023 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025

- Hilmer SN, Shenfield GM, Le Couteur DG. Clinical implications of changes in hepatic drug metabolism in older people. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005 Jun;1(2):151-6. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.1.2.151.62914. PMID: 18360554; PMCID: PMC1661619.

- Achterbergh, R., Lammers, L. A., Kuijsten, L., Klümpen, H. J., Mathôt, R. A. A., & Romijn, J. A. (2018). Effects of nutritional status on acetaminophen measurement and exposure. Clinical Toxicology, 57(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2018.1487563

- Tsuchiya Y, Sakai H, Hirata A, Yanai T. Effects of food restriction on the expression of genes related to acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity in rats. J Toxicol Pathol. 2018 Oct;31(4):267-274. doi: 10.1293/tox.2018-0009. Epub 2018 Jun 16. PMID: 30393430; PMCID: PMC6206280.

- Jamwal R, Barlock BJ. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Hepatic Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Enzymes. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020 Aug 29;13(9):222. doi: 10.3390/ph13090222. PMID: 32872474; PMCID: PMC7560175.

- Agrawal S, Murray BP, Khazaeni B. Acetaminophen Toxicity. [Updated 2025 Apr 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Staffe AT, Bech MW, Clemmensen SLK, Nielsen HT, Larsen DB, Petersen KK. Total sleep deprivation increases pain sensitivity, impairs conditioned pain modulation and facilitates temporal summation of pain in healthy participants. PLoS One. 2019 Dec 4;14(12):e0225849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225849. PMID: 31800612; PMCID: PMC6892491.

- Irwin, Michael et al. Sleep disruption and activation of cellular inflammation mediate heightened pain sensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. PAIN 164(5):p 1128-1137, May 2023. | DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002811

- Fang XX, Zhai MN, Zhu M, He C, Wang H, Wang J, Zhang ZJ. Inflammation in pathogenesis of chronic pain: Foe and friend. Mol Pain. 2023 Jan-Dec;19:17448069231178176. doi: 10.1177/17448069231178176. PMID: 37220667; PMCID: PMC10214073.

- Hodges RE, Minich DM. Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. J Nutr Metab. 2015;2015:760689. doi: 10.1155/2015/760689. Epub 2015 Jun 16. PMID: 26167297; PMCID: PMC4488002.